I was recently asked to do some research to assist with an application for British citizenship by descent. Clearly, something like this requires a very high degree of certainty in the evidence, and doing it prompted me to compare my own standards of evidence to that expected by the Passport authorities.

Not all ‘evidence’ is equal

Essentially, government authorities are interested in official documents: Birth, Marriage and Death Certificates; official Immigration documentation; dated Ships’ Manifests; Naturalisation documentation; and official documentation for any name changes. There is a clear difference between these types of documents, made during or just after the event and reported to an official person or office, and documents requiring the individual or their representative to give information many years later. In the latter documents, the information may be inaccurate, mis-remembered or even false. We have to give higher credence to the former.

Working on this research I was mindful of the ‘Windrush generation’: people from the Caribbean who were invited to the UK to help rebuild post-war Britain between 1948 and 1971. A few years ago, many of these people had their legal status in the UK called into question. Some were deported back to their country of origin where, after five or more decades in the UK, they had no connections, no close family and little or no personal history. I was confused. They had been paying taxes and made pension contributions: they must have left a solid paper trail. It’s just a question of gathering together school records, NHS, National Insurance numbers, births of children, bank records and so on… right?

It transpired that the reason for these problems was that the Home Office did not keep records of the ‘Windrush’ people to whom it granted indefinite leave to remain in the 1970s. Consequently, they were now requiring each person to provide four pieces of evidence for each year they had been in the UK. If any of them could not do this, or if they had left the country for a period of two or more years and had not applied for UK citizenship since the granting of their right to remain, they would be found to have relinquished that right. That’s a huge burden of proof.

Thinking about all this, I realised that essentially, the difference between sound genealogy research for family interest, and that required for a government body like the Home Office, does not necessarily rest on the standard of the research; it’s about the respective goals of each. The goal of any form of research should be an objective search for the truth. In this case, we’re looking for evidence to prove or disprove a connection between one generation and the next. Yet the Passport authorities are gatekeepers, and their role is more akin to an audit: ‘We require originals or certified copies of documents A, B, C, D and E. Alternative documentation may be offered, but our decision is final.’ The default position is ‘No’, and the highly rigorous burden of proof is on the applicant.

If we, as genealogists, were so inflexible in our evidence requirements, we would pretty soon find many of our ancestral lines coming to a halt. One of the skills we need to develop is ‘thinking outside the box’. Getting to the truth is essential, but if we can’t find the standard documentation evidencing a connection between two people, we have to come at it from another direction. We find another way, and then we look at it in the round: taken together, does all this documentation point to X being the parent of Y? If there is any doubt, this must remain a ‘probable hypothesis’. For me, this is one of the most enjoyable parts of the research: the detective work, and the satisfaction when it all comes together and we can reflect on the creativity that went into working it all out. But in the event of an essential document being missing, would a Home Office civil servant be prepared to consider my ‘work-arounds’? This was something of which I had to be ever-mindful during that research.

Thinking of all this more generally, it presents a perfect opportunity to reflect on the varying ‘credibility’ of the different types of evidence we use to demonstrate a familial connection between named individuals. Let’s consider this now in relation to just one official document. Let’s say the Birth Certificate of person B, parent and therefore essential in the lineage from person A in another country to B’s own parent, person C who was a British-born UK citizen, is missing; and we don’t even know in which of the two countries person B was born. Perhaps the country in question didn’t have Civil Birth Registration at the time of the birth, or perhaps the records of the entire country were destroyed, as happened in Ireland. What does a Birth Certificate prove? And therefore, in its absence, what information is ‘lost’ and may need to be proven via another route?

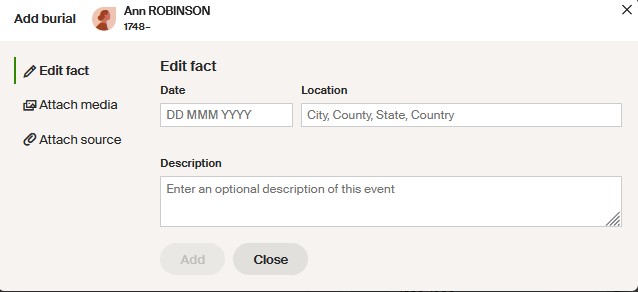

I have a Birth Certificate in front of me. It includes:

- Name and sex at birth

- Date and place of birth

- Name of both parents, including mother’s maiden name and father’s occupation

- Name and address of informant, and the date on which it was registered.

- Detail of the Registration District, some reference numbers, the name of the Registrar and, if this is the original, that person’s signature.

- If I search for this birth online, I see a summary of some of that information, together with the volume and page of the entry in the England & Wales Civil Registration Birth Index.

It’s the official version of ‘the truth’ of the birth. Yet even official Birth Certificates are not necessarily entirely true. There are cases in the past of parents giving a later birth date to avoid paying a late entry fee. There are, of course, named fathers who are not the biological father. Historically, there might even have been grandmothers who registered the child as their own to avoid an official record of their very young daughter giving birth to a child out of wedlock.

Despite these possible inaccuracies, the Birth Registration is the accepted, official version of where and when a person was born. When trying to prove the right to citizenship on grounds of ancestry, it’s an essential document, but even when simply working in the pursuit of family history with no legal consequences, it’s a vital document. What alternative forms of evidence might we draw upon; and to what extent do these alternatives have equivalence with the original?

Baptism records

These usually link the named person to named parents and therefore demonstrate parentage. The baptism of a baby evidences that the child was born by the date of the event, and if the record includes the date of birth, a recent birthdate is highly likely to be correct. However, sometimes children are baptised as a group, when some of them will be older, even teenagers. They place the named people in that certain place at that certain time. What these ‘batch’ baptisms cannot do, however, is evidence the birthplace – town or even country – of the named person. They might also not evidence the parental link if, for example, one of the parents has remarried before the batch baptism, and that step-parent is named.

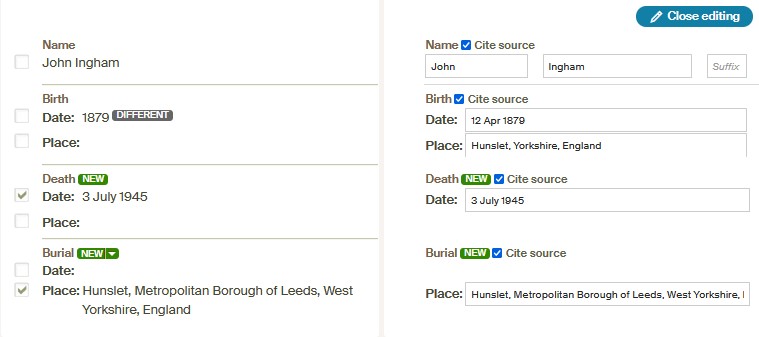

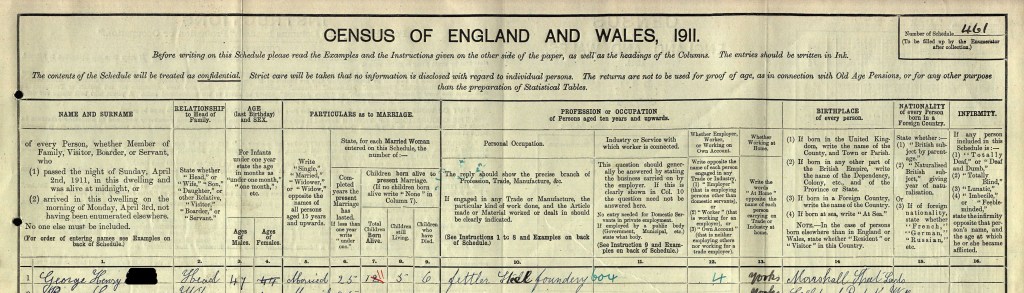

Census records

These link the person to their parents (or adoptive parents, or a step parent) and place them in the family setting. They can also help us to home in on a year of birth, and will also help us to narrow down the year of any migration (between countries or between different parts of the UK) since different children may have different birthplaces.

However, the information on censuses is provided by the head of household. At the strictest level of interpretation, all they really evidence in terms of location is that all the named people were at that address on the night of that census – and even that might not be true. For example, if your teenager was having a sleepover at a friend’s house you would probably include them at your home, even though they were actually ‘visiting’ at the other house. Here are three examples from the records to illustrate how what is recorded may not be true.

In the following example George Henry is recorded as having been born in Marshall Street, Leeds. The person who completed this census form was George Henry’s wife. She is my great grandmother, and I love her for all the extra, un-asked for, pieces of information she included on it! The name of the street, here, for example, was not required, but the fact that she wrote it really beefs up the likelihood that George was born there. Only, he wasn’t! He was born in Crewe, Cheshire; and all other censuses, together with his actual birth certificate, evidence that. I would assess this as a genuine mistake.

In the next example, Joseph Appleyard is shown living with three children. Daughter Rachel is 22, son Joseph is 17 and son James is one year old. However, James is not Joseph’s son. In fact he was born eighteen months after Joseph’s wife died. He is Rachel’s son, and the birth certificate shows this. Yet if the birth certificate could not be found this fact would be mere speculation. I would assess this as either a desire to cover up the birth out of wedlock OR possibly an assumption on the part of the enumerator.

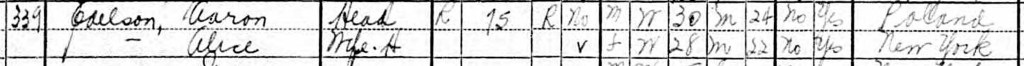

Finally, the following example shows an extract from the United States Census of 1930. Alice Edelson is the daughter of Solomon Rudow whose connection to family in the UK was featured in my last two posts. My research around Solomon and his family was focused on identifying a birthplace for him, so that it could be compared to that of his UK-based sister, and by extension, the likelihood of the family having roots in that place of birth. Given that this family immigrated to the US, the recording of Alice’s birthplace was important to my research. It would also, of course, be important in any application for citizenship back in the country of origin for descendants of Alice, where the number of generations since the birth of an ancestor on that soil is critical. Here, Alice’s place of birth is recorded as New York, yet in every other Census it is recorded as Poland or Russia.

Birth announcements in newspapers

We would certainly accept a newspaper announcement of the birth as evidence of the date, place and parentage of a child, and provided the announcement appeared in the newspaper shortly after the birthdate shown, there seems little reason for a legal authority to refuse to accept this, particularly if combined with other documentation pointing to the same facts.

Wills

A Will is unlikely to evidence country of birth, but can certainly evidence parentage or other familial connection, and possibly help to narrow down a birthyear. For example, a Will may refer to ‘my oldest child Isabelle’, thereby indicating that Isabelle was born before the second child, whose birthdate may be known, but probably after the marriage of the parents. This could narrow down a likely birthyear to just three or four years. Alternatively, a testator known to be the sister of Isabel’s mother, may refer to ‘my niece Isabel Bloggs’, thereby evidencing the parentage from a different direction.

Any record in an adoptive country in which someone provides place of birth

We have already looked at Census records, and noted how they might be incorrect. Working with Birth and Death records in a number of countries with a very large population of first or second generation immigrants, I note that information was often asked about the person’s place of birth, and even sometimes the place of origin of the parents. Death records in particular have weaknesses when it comes to this matter, since the information is necessarily provided by someone other than the deceased. For us as genealogists, this information can be very useful because it points us to where we might find a birth record. However, it might not be true: the informant may have guessed. The birthplace of a 3x great uncle of mine who was transported to Western Australia in 1867 was recorded on his death record as Yorkshire West Riding. All UK census records before his transportation indicate that he was born before the family migrated to England from Northern Ireland. He was very young at the time and may possibly have never known.

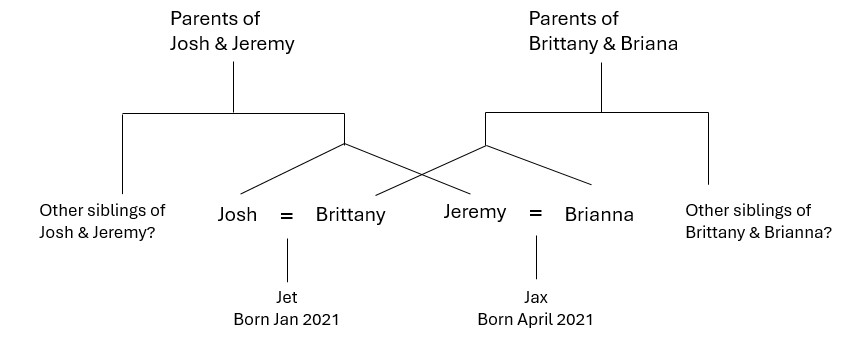

DNA

Provided the right ‘cousins’ have also tested, DNA can prove beyond any doubt that a person is descended from a parent, grandparent or great grandparent, but it will not of course evidence where the person was born.

Records relating to others

Marriage records for the parents and any records relating to other children, such as birth or baptism records, have value in helping us to home in on likely dates. They do not prove anything in relation to the birth of our person of focus (unless the Birth certificate in front of us is the twin of our person) but have value in helping us to build a picture.

To summarise

The more experienced we are, and the more we focus on getting to the truth of the matter, the better we become at finding and combining information from a selection of sources to build a picture of the facts. Individually, none of the above alternative records fully evidence all the facts on the Birth Certificate – although Birth announcements in the newspaper and very early Baptisms may come close. However, by combining evidence from several of them we may be able to arrive at a pretty close picture that we, as genealogists, can accept as proof of an individual’s date and place of birth and their parentage. Ultimately, the difference between the level of proof of an excellent genealogist and family historian researching for personal interest, and that required by government bodies such as the Passport Office may not rest on the research itself, but on the point at which the weight of the evidence is accepted by the authorities as tipping the balance. Nevertheless, this has been a useful comparison in encouraging us to hold a light up to our own standards and consider if they truly are watertight.