Last week we looked at two types of name changes we all have in our trees: women upon marriage and changes from the days before our surnames had settled spellings.

This week I want to move on to deliberate changes of name by the individual. Here are some examples from my own tree. Perhaps you have something similar in your own.

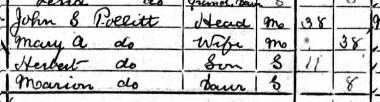

Informal adoption

I mentioned a couple of posts back that my great grandfather was given by his mother to her sister in law, who brought him up as her own son. Prior to The Adoption of Children Act, 1926, adoption was not a legal process, so these types of informal adoption were the norm. I have no idea if my great grandfather knew that his ‘mother’ was in fact his aunt. In one census she listed him with his birth name but certainly by adulthood my great grandfather had assumed his adoptive surname, and this was the name passed on to future generations.

Deed poll

A number of people in my extended family changed their name formally by deed poll. Some changed their first names as well as the surname.

Informal use of a different name

Several people changed their surname without the formality of deed poll. Some experimented with more than one surname before finally settling on the one they preferred. Yet more changed names several times on immigration into the United States. (These took a lot of detective work to find!) There were a variety of reasons for this, and looking at their wider stories I can see why each of them did it.

How do we record such name changes on our trees?

What distinguishes all these examples from the convention of women changing name upon marriage and historic spelling changes is that here, someone has made a deliberate decision (or had a decision made for them by adoptive parents) regarding how they would like to be known, and our names are such an important part of our identity that I want to honour that decision. But how do we do this whilst remaining true to the basic rule in genealogy that the name we put on our family tree is the one first recorded for that individual?

I spent some time trying to identify the ‘good practice’ for dealing with this. It turned out there is no such recognised good practice. 😦

I also don’t think any of the online or software trees deal with it very well. While all have the capacity to indicate a change of name within the facts timeline, only one name can be shown at the top of the person’s profile. What do you choose? Either James and Joanne Bloggs seem to have given birth to two Bloggs children plus another child whose surname is Jones, or we ignore the decision made by that third offspring to be known by another name. We can of course make use of notes to explain what happened, but what I would like is for the change of name event to trigger a second ‘field’ on the person’s profile, so that it clearly indicates both names, in the format:

Name: John Bloggs

AKA: John Jones.

In the absence of this, my personal solution has been to include both names in the surname field, using the format John Bloggs / Jones. It may mess up the search facility, but I feel happier with that compromise than with leaving out one of the names.

If you want to explore this further, here’s a useful online discussion on the topic.

And here’s a helpful video from Ancestry outlining reasons why people may have changed their name. From around 13:15 it deals with different ways of recording those changes on your Ancestry tree.

*****

I’ll be taking a short blog break next week, but will be back as usual the following week.