In a previous post about Death Certificates I talked about a whole range of alternative records that could provide sufficient information about a person’s death to make purchasing the official certificate unnecessary. Today I want to return to this topic but with a different focus: to consider how these same records, purportedly confirming a person’s death, might tell us a great deal more about their life.

We know that after 1837 Death Certificates record specific information: the deceased’s name, age, place and cause of death, occupation (husband’s occupation if a married woman or widow) plus description/relationship and residence of informant.

Yet these facts of the deceased’s death start to give us clues about how they lived. Did they live to a ripe old age or die young? Does the cause of death suggest anything other than natural causes, e.g. an occupation-related disease, an accident, a suicide? Was the informant a close relative? If not the spouse or adult son/daughter, was it a sibling, indicating that the family remained close both geographically and in kinship? If we then also add in some of the alternative sources of information about deaths (I listed them in that previous post), we might find we can learn a surprising amount of additional information. Here are four quite different examples from my own research:

Coroner’s Reports

On 17th March 1898 my 2xG grandfather, Edward, took his own life. The death of a person in unexpected, unexplained or violent circumstances triggers a Coroner’s hearing. Where records of these survive they will be at the local Archives/ Record Office. Sometimes they are quite brief, but Edward’s isn’t.

The Coroner interviewed four people: the bridge turner who was the last person to see Edward alive: the coal boat master who found his body in the water; and the woman who strip-washed and laid him out. The principle interviewee was Edward’s daughter, my great grandmother, Jane. Between the four of them they provide information about what happened that day.

But Jane also talks about how Edward was in life. She paints a picture of him in the days and weeks leading up to his death. He smoked his tobacco but had a serious, ongoing bronchitis condition (they probably hadn’t worked out the connection by then); he received 3 shillings a week from the Poor Law Guardians; he had a life insurance policy with the Prudential (I wonder if they paid out for suicides). She visited him daily, and had seen a change in his behaviour – he had become very ‘irritable and childish’ during the past 3-4 weeks.

I learned that Edward lived in a ‘yard’, above a stable. He had given notice but had not yet left. A few days before Edward’s suicide, the occupier of the stable below had ‘insulted him’, causing him to fear that the stable occupier would return on St Patrick’s Day to break all his windows. Whatever happened, and whatever was at the root of the animosity, it was clearly weighing heavily on Edward’s mind.

The reference to St Patrick’s Day is intriguing. What was the significance? Edward’s first wife was Irish, but she was long dead; and although I’ve never found Edward’s baptism, family legend has it that ‘he went back to the place where he was born to drown himself’. Have I been looking in the wrong place: could Edward have been Irish? Edward is the enigma that keeps on giving.

Obituaries

If your ancestor was particularly grand or achieved something noteworthy in their life, you may find an obituary in the local/ national newspaper or other publication.

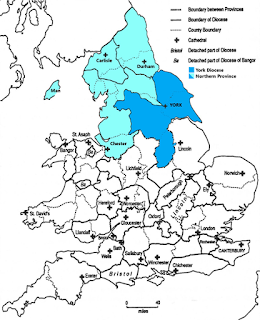

My 4xG uncle Edwin Wade, was Lord Mayor of York in 1864-65. A successful surgeon-dentist, he was active for many years in local politics, a ‘mover and shaker’ in many public bodies, and an early investor in the railway company. I hadn’t appreciated just how much of a pillar of the community he had been until I read his obituary in the York Herald, 13th December, 1889. (FindMyPast newspaper search.) There, I learned that Edwin was also senior Justice of the Peace and associated with public bodies such as the Lunatic Asylum, School for the Blind, York Tourists’ Society, York Savings Bank and the Merchant Taylor’s Company.

Edwin’s funeral was a huge event. As the cortège passed through the streets of York, the whole city came to a standstill. Blinds were drawn on the Mansion House and other public as well as residential buildings; shutters were closed on local businesses. A comprehensive list is given of the York great and good who attended, and also all family members. This helped me to track down a number of marriages and other connections.

Wills

For any ancestors who died since 1858, you can search the government’s wills and probate website to see if they left a will. Be sure to enter your search (surname and exact year of probate – which may be after the year of death) in the correct section: 1858-1996; 1996 to present; or soldier’s wills. Once you’ve identified the correct person on the ‘Probate Calendar’ you can order a digital copy of the actual will (cost £10) which will be emailed to you.

Wills can tell us a huge amount about our ancestors and their families, and I’ve ordered quite a few over the years. However, in the example that follows, just the information on the Probate Calendar was enough to solve my current problem:

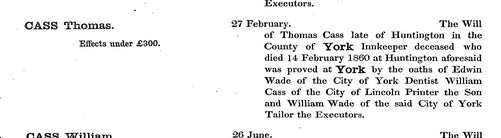

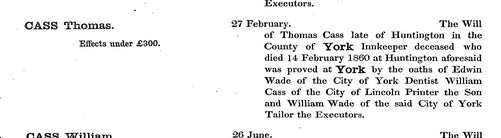

I had traced one of my lines back to a William Wade in York, and I knew his wife (my 3xG grandmother) was Jane, but wasn’t yet sure either of Jane’s maiden name or of William’s parents. One of the possible marriages was to a Jane Cass in Huntington, daughter of Thomas, an innkeeper. Possible parents for William were John Wade and Sarah; and if this was correct, I had found baptisms for all of William’s siblings. I entered all this on my tree, noting that it was not yet proven. Some time later I found a likely death for Thomas Cass, and then an entry on the Probate Calendar:

I could have ordered the actual will and I’m sure I will, eventually. However, although this short entry told me only one thing I didn’t know about Thomas (he left ‘Effects under £300’), it proved without doubt that all parts of my hypothesis about this line were correct. It linked my known 3xG grandfather William Wade to Thomas Cass, and even included William’s older brother, Edwin. Strange I thought at the time, to name the brother of your son-in-law as the chief executor… Of course, that was before I knew that Edwin Wade was your all-singing all-dancing politician, board member, soon to be Lord Mayor of York, and in general the man to trust if you wanted something done!

Monuments, epitaphs, etc, in churches

For reasons that deserve a separate post it’s not always clear if our ancestors were Nonconformists. For years I couldn’t find a baptism record for my 3xG grandfather, John Ingham. Eventually a possible emerged. Everything made sense: the location (Morley), the year, even the names of the parents and siblings which I could see repeated in his own children. The only problem was that adult John seemed to be Church of England. He married Betty in her C of E parish church (Calverley), and all their children were baptised accordingly. But this baptism was in an Independent chapel. I dithered for a long time over whether to accept this record as John’s. In the meantime, continuing to research other lines, I gradually realised that a lot of my other ancestors came from Calverley and adjacent villages – and they were all Nonconformists. There seems to have been large communities of different Nonconformist congregations in a triangle taking in Calverley, Pudsey (Betty’s actual birthplace) and another village called Idle. Might there also have been some sort of connection between these congregations and that of Morley, where the possible baptism for John took place?

It was a memorial inscription that made everything fall into place, erected in 1880 to the memory of Betty’s brother Abraham Gamble, by his wife Elizabeth.

How on earth could this have helped? Well, it’s to be found in Pudsey (Betty’s birthplace), on the wall of the Wesleyan Methodist Church, thereby confirming Nonconformity in Betty’s wider family. It followed that my 3xG gradparents Betty and John might have met on social events between their respective congregations, and therefore the unexpected Nonconformist baptism record for John could be correct. Together with all the other information, I was now happy to accept the John on the baptism record as my John. It may seem tenuous, but afterwards, I did find that Betty and Abraham’s mother, Hannah, had also been baptised in the Morley chapel, moving to Pudsey after marriage. The connection between the two families was an old one; but it was that memorial inscription that tipped the balance of probabilities for me.

As I hope these examples illustrate, we can look upon these death-related records as simply a confirmation of names, dates and places. Or we can really look at them, wringing out every last clue to better understand our ancestors’ lives.

Do you have any similar examples? Or are there perhaps as yet unseen clues lurking in the death records on your tree?