Civil Registration of Births, Marriages and Deaths (BMDs), together with the districts, offices and officers required for the administration of the new system, was introduced on 1st July 1837. In theory, these life events of any ancestor or family member born after that date, or if they’re older, marrying or dying after that date, should have been notified to the appropriate local office and recorded by the state. That said, registration was not actually mandatory until 1875, and in the early years there was confusion. People were used to registering births (or baptisms), marriages and deaths (or burials) with the church, and it took a while for some to realise they now needed to register at a government office. However, certainly by 1875 everyone should have been registered using the appropriate channels, and the civil BMDs are an invaluable resource for anyone researching their family history.

But does that mean we *need* them? Let me explain my thoughts.

As genealogists we start with what we know and we work backwards. The period leading back to 1837 is the easier part, when we can compare and cross-reference family members listed on the censuses and the 1939 Register with the civil records of Births, Marriages and Deaths and probably Baptisms, Marriages and Burials within the parish church. Obviously, then, this is where we start as beginners, and where we make our mistakes. One thing I’ve noticed, over the years of seeing posts from inexperienced researchers online, is an assumption that it’s necessary to buy all the certificates. That’s a huge outlay. If we exclude ourselves and our parents but include all other direct ancestors born or still living after 1837, this could amount to 4 grandparents, 8 great grandparents, 16 GG grandparents and maybe 32 GGG grandparents. That’s 60 ancestors, each with perhaps a birth certificate, one or more marriages, and a death certificate… possibly as many as 150-190 certificates to buy at £11 each (or £7 if a PDF is available). That’s £1650 – £2090. If we wanted to add in the records for all children born to our direct line, the cost would be astronomical. Taking one of my grandparents as an example, I counted back all direct ancestors and children born to them after 1837: one hundred and eleven people. Times that by four to get a rough estimate for all my grandparents, and that would be four hundred and forty four people, all with births, deaths and maybe marriages. There’s no way I could have justified that outlay.

We need to work out alternative ways of getting the same, or most of the same, information. Our starting point, then, should be to know what information is on each historic certificate.

Civil Birth Certificate

This includes:

- Registration District, Sub-district and official reference numbers

- Where and when born

- Name (if decided at time of registration)

- Sex

- Name and surname of father

- Name, surname and maiden surname of mother

- Occupation of father

- Signature, description and residence of informant

- When registered

- Signature of registrar

- Any name registered after registration

Civil Marriage Certificate

This includes:

- Registration District, Sub-district and official reference numbers

- Where solemnized

- When married

- Name and surname of bride and groom

- Age of both

- Marital condition at time of marriage (bachelor, spinster, widowed)

- Rank or Profession of both

- Residence of both at the time of marriage

- Father’s Name and Surname of both, together with fathers’ Rank or Profession

Civil Death Certificate

This includes:

- Registration District, Sub-district and official reference numbers

- When and where died

- Name and surname

- Sex

- Age

- Occupation

- Cause of death

- Signature, description and residence of informant

- When registered

- Signature of registrar

Do we need all this information? Is it available anywhere else?

As a beginner I realised that my primary need was to move my research back in time, while ensuring I had the right people… alongside the need not to bankrupt myself! Therefore at that stage I could dispense with cause of death, for example, but I did need to know the parents’ names to help me move backwards and ensure I had the correct people. So here are a few examples of certificates I did buy, and others I didn’t, on the basis that I could get the information I needed from other documents, and other information was not yet essential to my needs.

Church of England marriage registers – the information on these is exactly the same as on the civil marriage certificate. If digital images of the original CofE parish register is available online via your genealogy website of choice, then you don’t need to buy. In fact, the parish register entry is better, because you will definitely see the couple’s signatures (or marks), and signatures could be used later for comparison with other documents. The only civil marriage certificates I have ever bought are those from Catholic churches (which unfortunately are still not widely available other than via the actual parish administrator or occasionally via local record offices), another that was solemnised in a Nonconformist chapel, and one other marriage for which I could find no digital images of the parish register available online.

Births – If you know the mother’s maiden name and if you have census returns showing all children of the family and their places of birth, you will probably be able to find all the births on the GRO Online indexes. You may also find some additional children who never made it to a census. The online index doesn’t give the actual date of birth; rather it gives the ‘quarter’ in which the birth was registered: M quarter being the three months ending March, J quarter being the three months ending June, and so on. As a beginner this may be sufficient for your needs, particularly for siblings of your ancestor. That said, you may find the additional information elsewhere. The 1939 Register includes the actual date of birth (for some reason it is often a year out, but the day and month are correct). You may also find more information on a baptism register entry: along with child’s name and date of baptism there will be both parents’ names, abode, father’s occupation and possibly the date of birth. A newspaper announcement of a birth will also give some of this information. In these early stages, where I did buy a birth certificate, this was to solve a puzzle. I bought one before the mother’s maiden name was included on the online index and I couldn’t find a marriage using only the father’s surname. (I still have never found the marriage.) Another was purchased because there was some intrigue surrounding the child’s actual birth parents (by the age of five he was informally adopted by another couple). Another, again, because of the inaccessibility of Catholic parish registers, and so on. If I could find almost all the information by other means that was acceptable.

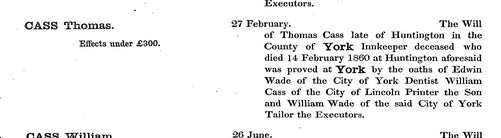

Deaths – again, you can often narrow down the death to within a few months using the GRO Online indexes. Alongside the quarter and the registration district, the inclusion of age at death can help you to distinguish between deaths of other people of the same name – although we do need to allow for a little flexibility since the age is provided by the informant who may have guessed it. After 1858, you might also find the actual date of death and other useful information from the National Probate Calendar (without the need to purchase the Will, although at only £2 for a digital download I would get the Will anyway). What I really love, though, is a good municipal cemetery register. For example, my 4xG grandmother’s entry in 1860 at the York Fulford Road Cemetery (freely available on FamilySearch) gives her name and age at death, date of death, date of burial, the name of her husband and his ‘rank, trade or profession’, their residence, cause of death, the name and details of the informant and the officiating minister. Why on earth would I need to buy the death certificate?! This is the best register I’ve ever come across, but others come fairly close in terms of information recorded.

Again, even in my early years, there were times when the information I could get from the GRO index and the burial record wasn’t enough. For example, the death of a small boy with the very unusual yet exact same name as someone else in my tree, but in a completely unexpected location could only be confirmed as my family by the purchase of the civil death certificate. His sad death at such an early age also gave me additional information about his parents – that they had spent a short period in the early years of their marriage in a different county.

More advanced reseachers are likely to have different needs

All of the above relates to the nuts and bolts of building our family trees back to the introduction of Civil BMDs. There is no doubt that the information on each of the certificates will give us something useful to enable us to do this, but given the cost of each one, the goal so far has been to try to find that information elsewhere, even to go without a little information at this stage if most of it can be found using other documents.

As we progress, our needs change. Research becomes less about the nuts and bolts and more about the ‘family history’, or the stories of our ancestors’ lives. I will never need to buy the death certificate for that 4x G grandmother, or any of my other ancestors and wider family in the York Fulford Road Cemetery, but on occasion I’ve bought certificates for other individuals simply out of curiosity about their story. For example, the husband of a great aunt whose service record indicated he suffered a ‘severe shell gas wound’ in 1918 and who was not remembered with much love by wider family members. I read that many of the men who survived mustard gas attacks went on to die of tuberculosis, generally before or around the time of the outbreak of WW2. I could see that this person died in 1935 and wondered if TB was the cause. It seemed to me part of his story, an explanation perhaps for his behaviour, and part of the wider story of my own grandparents. So this was one of the certificates I bought more recently. Another story that intrigued me was the death six months apart of two GG grandparents, resulting in the orphaning of their large family and my own great grandfather being brought up in the workhouse from the age of six. I bought their death certificates just to find the two causes of death. Conversely, I’ll shortly be visiting the archives where microfiche copies of the Catholic registers for lack of availability of which I’ve already bought civil certificates. From these registers, I’ll be hoping to get names of the sponsors, which may help to broaden out my understanding of any other family members that came with these ancestors to England.

There are of course other examples like these ones, where I’m prompted by completion of ‘the story’ to buy the certificates, but in general I’m still of the ‘keeping costs to a minimum’ mentality. If you’re fairly inexperienced as a family history researcher I hope this has helped give you some pointers. If you’re an old hand it would be interesting to know how this compares with your own practice. Have you any examples of nuggets found in a unexpected source? Or perhaps of how eventually buying a certificate solved a mystery or completed a story? Do leave a comment!