In theory, we should be able to follow our paternal line with the same surname back through the generations, certain that it will continue beyond the earliest parish registers. If you (or a direct male descendant from your paternal line if you’re female) were to take a Y DNA test, then again in theory – provided there are no unexpected paternity events – you should even find the Y DNA haplogroup keeps step with the surname, right back through history. Our paternal line, though, does not comprise only endless lines of grandfathers. There is an equal number of grandmothers, and in just the same way that our foremothers married into the male surname and refreshed the gene pool, so too she refreshed the family’s traditions, recipes, ways of keeping house and, significantly for the topic of this post, the names given to children.

I wrote in two previous posts about naming patterns: the tradition of naming children in a specific order based on the names of their grandparents, parents and other significant family members. You’ll find those previous posts here (Irish) and here (English).

My last two posts have demonstrated that historically, women are significantly less likely to appear in official records. Their role was within the home, and in general the home was not a matter for public record. As we have seen, we have to get in the habit of reading between the lines regarding information about our female ancestors. For all these reasons their importance within society as a whole can easily be overlooked. Nevertheless they did have influence, even though their primary sphere of influence was domestic.

Today’s post will draw together all these topics. It’s a case study of a puzzle solved by focusing on traditional English naming patterns, and it highlights the importance and potential benefits for us as researchers of the merging of the women into the family.

When I was very young a fairly close member of my family married a lady with the same surname as his own. In more recent decades, as I progressed my genealogical research I found that this surname line on our side could be traced, still in Leeds, all the way back to the 17th century. I wondered if the same would be true for the paternal line of that lady marrying into my family, and if we would turn out to be distant cousins. Since this person is living I have changed the names. I shall refer to her as ‘Rose’, and to the surname we share as ‘Beccles’. Apart from these false names, all other information is accurate.

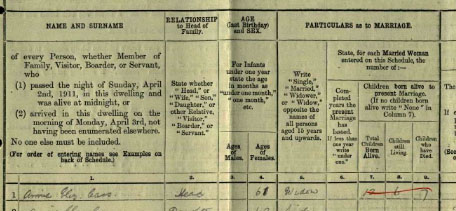

It was about ten years ago that I first started to work back ‘Rose’s’ paternal line. I knew her father’s name and was able to place him with his family in the 1911 census. From there, the preceding four generations were quite straightforward:

- His father, Frank, residing with him in that 1911 census, was also located as a child in 1891;

- Frank’s father, Samuel, residing with him in the 1891 census, was located with his own birth family in 1851-71.

- Samuel’s father, Francis, was to be found with his birth family including father Samuel in 1841, and a baptism for Francis, son of Samuel was found in Leeds.

- Samuel’s marriage a couple of years before that was also located, and his own baptism was in 1795. His father was Thomas.

I had now traced ‘Rose’s’ paternal line back to at least 1795, and I had the name of his father, Thomas. There was so far no connection between this and my own ‘Beccles’ line, but certainly both families were still in Leeds. I now needed a baptism for Thomas, probably around 1770; and this was where my research came to an end: there were too many Thomas ‘Beccles’ baptised in Leeds within a reasonable timeframe for me to be able to decide with certainty which was the correct one.

The solution came from an unexpected source. About five years later I discovered a new record set on Ancestry: the Leeds Township Overseers Records Apprenticeship Register. It seemed to start around 1740 and to continue until the end of the 18th century. I carefully searched the register, looking for any of my ancestors or their siblings, and found two of my ‘Beccles’ boys: my 4x great grandfather and his brother Nathaniel. It was Nathaniel’s entry that intrigued me: he was apprenticed to a master tailor by the name of Francis ‘Beccles’. I immediately started to wonder if there was some family connection between my Beccles line, known to be clothworkers, and this Francis.

Then I had my brainwave: ‘Rose’s’ ancestral ‘Beccles’ line and my own line had completely different forenames. Whereas the boys’ names repeatedly handed down in my line, prior to the 20th century, were Joseph, Nathaniel, Leonard and Benjamin, in ‘Rose’s’ line the naming tradition so far featured Samuel, Thomas and, significantly here, Francis. Could this master tailor, Francis ‘Beccles’, to whom my Nathaniel was apprenticed, be part of ‘Rose’s’ direct line?

I then started to wonder why this situation of two lines with completely different naming traditions might have come about, and the answer, when you think about it, is obvious. A surname is static. What gives it life is those who join it – in other words, the women who come into the family as wives. If we go back to the traditional naming patterns: the first son will take the name of the maternal or paternal grandfather; the second son will take the name of the other grandfather, and so on. What changes is that every wife at each new generation brings into the mix the name of her own father, her own mother and her own name. In my ‘Beccles’ line I knew who brought in Nathaniel, and I knew who brought in Leonard. These were the fathers’ names of my 6 x great grandmother and my 4x great grandmother. So now I needed to see if I could do the same for ‘Rose’s’ line, and if I could use this to help me find the correct baptisms for each generation further back. This would involve:

- identifying all potential baptisms for Thomas ‘Beccles’, including the name and abode of the father;

- guided by fathers’ names, abodes and dates, identifying baptisms of all other children born to these same men;

- placing the children in age order so as to identify first-born and second-born sons (normally named for maternal and paternal grandfathers);

- checking also the names of third-born sons (which should be the same as the father’s name, unless that name has already been used);

- based on all this, identifying any family/families with strong similarities in children’s names with those given by Thomas and his wife to their children. i.e. In addition to the baptism for Thomas, was there also a Samuel, a Francis, and perhaps also daughters with names Thomas and his wife passed on;

- homing in on the most likely family/families, using the date of the first-born child to identify a marriage, likely within two years previously. This would provide Thomas’s mother’s name;

- and finally, looking for the baptisms of Thomas’s mother and father to ascertain their own fathers’ names.

- And repeat, back through the generations.

Remember here that what we’re looking for is adherence to the traditional naming pattern. It may not hold good, but if it does it’s an extra bit of ‘evidence’ indicating your decisions so far have been valid. Remember also the extra value of finding the mother who brings a new name into the family, particularly if it’s an unusual name. It’s strong evidence that your research is correct.

For the avoidance of doubt, let me tell you – you really have to be ‘in the zone’ to do this!

But I did it! I found Thomas’s baptism. He was the first-born son of Samuel, the name given to Thomas’s own first-born son. Thomas himself was named for his maternal grandfather, Thomas. The master tailor Francis, whose name had started the alarm bells ringing turned out to be the nephew of this Samuel – son of his older brother George. So – our first identifiable ‘connection’ is that my 5x great uncle Nathaniel was apprenticed in 1789 to ‘Rose’s’ 1C6R (first cousin six times removed). I still haven’t found our common ancestor, but I’m working on it.

Using this method I managed to get ‘Rose’s’ paternal line back to the marriage of her 9xG grandparents in Leeds in the year 1627. When I passed all this information to ‘Rose’ she was astonished to see that two significant names still in her family – Frank (originally Francis) and George – had been handed down in her paternal line for several centuries. How amazing is that?!