If you know Norwich you may recognise this scene, captured from The Forum. The 15th century church opposite is St Peter Mancroft. The significance of this scene for me was not only the reflections of the super-modern structure juxtaposed with the historic church, but also in the fact that here I was with my son, inside the modern structure in the year 2019, looking out on that ancient church inside which, 230 years earlier, my 4x great grandparents were married, and six years after that my 3x great grandfather Thomas was baptised.

All of this is relevant to the tale that follows. It follows on from my last post about the operation of ‘settlement’ as the key concept in dealing with the poor.

I was in Norwich visiting my son, spending each evening with him and passing the days while he was studying, at the county archives or walking around the churches and parishes of significance to my Norwich ancestors. Amongst others, I was on the trail of the aforementioned Thomas and his wife Lucy: my 3x great grandparents. After marriage they settled in another Norwich parish: St Martin at Oak. Yet the baptism records of their children were puzzling: five children born in St Martin at Oak between 1819 and 1828, then a daughter born two hundred miles away in Fewston, Yorkshire in 1830, another son back in St Martin at Oak in 1832 and then seven more children in Fewston and Leeds between 1834 and 1846.

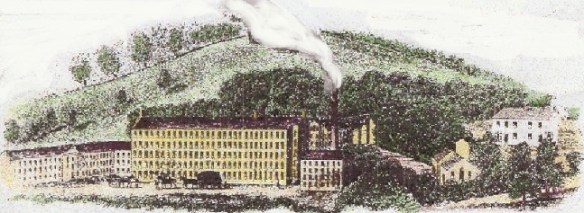

I understood why they had moved to Yorkshire. Thomas was a weaver: the very trade upon which Norwich’s wealth had been built; and yet even by the time of Thomas’s apprenticeship weaving was on the decline in Norwich, and with that the city itself. Quite simply, Norwich was unable to compete with the new spinning and weaving mills located in other parts of the country alongside fast flowing water and ready coal supplies. And so Thomas traded in his cottage industry lifestyle, working long hours at his loom beside the trademark long weavers’ window on the upper floor of the family home, for a position spinning flax at West House Mill at Blubberhouses within the parish of Fewston, about eight miles from Harrogate.

Typical Norwich weavers’ window

It’s known that the owners of West House Mill toured workhouses and charitable institutions in London and other large towns in search of hundreds of apprentice children, just as Thomas’s orphaned contemporary Robert Blincoe (‘The Real Oliver Twist’) had been ‘recruited’ around 1800. In fact, they hold the dubious honour of being amongst the first to do that. It’s reasonable to suppose, then, that Thomas might have been persuaded to relocate to the mill as an ‘engine minder’ while the owners were on a recruitment drive in Norwich. Reasonable, too, to imagine that all the benefits of this new life were highlighted, and little of the reality. The fact is that West House Mill was a huge, noisy, five-storeyed mill in a remote position in the Washburn Valley on the southern edge of the Yorkshire Dales. The working day, starting at 5am and ending sixteen hours later with perhaps just an hour’s break for rest and a midday meal, was hard-going and repetitive. The mill depended on the slave labour of the pauper children, effectively imprisoned there until they reached the age of twenty-one: it was a place of misery. While workers’ cottages were provided and the beauty of the countryside undisputed, the culture shock for Lucy and Thomas, used to the milder climate, the facilities of Norwich, the tranquillity of detailed work at the handloom and family nearby would be immense.

There was very little risk for the mill owners in employing Thomas. In accordance with the law, it’s almost certain that he left Norwich with a Settlement Certificate. Ever since the 1662 Settlement Act these certificates had facilitated migration by serving as a guarantee from the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor of the ‘home’ parish to those of the intended ‘host’ parish that, in the event of difficulties resulting in an application for poor relief, the home parish would pay the costs of ‘Removal’.

West House Mill at Blubberhouses, Fewston, Yorkshire

Two days after taking my ‘ancient and modern’ photo I was back in The Forum. Alongside several restaurants, the building is home to the Norfolk and Norwich Millennium Library which includes the Norfolk Heritage Centre. Here, I came across a reference to Thomas, Lucy and their first four children: a Removal Order dated 1826. This surprised me on two counts. First, based on the baptism records I had believed their initial migration took place between 1828 and 1830; and second, if my family had been removed from Fewston back to St Martin at Oak in Norwich, what was the reason for this, and why had they returned there in time for the 1830 baptism of their sixth child?

The detail of the Removal Order was even more unexpected. In 1826 Thomas, Lucy and their four named children (6 years to 3 months) were removed from St Martin at Oak, where they had ‘lately intruded themselves contrary to the law relating to the settlement of the poor, and that they had there become chargeable’. By decision of two Justices of the Peace they were to be returned to the last legal place of settlement, and that was Fewston in Yorkshire.

I confess that until this point I had misunderstood the full draconian extent of the application of ‘settlement’ in the operation of relief of the poor. While fully understanding the rules for acquisition of settlement rights in a new parish, my understanding had been that an individual would always retain rights acquired by birthright. In other words, that the granting of new settlement rights was a privilege and an additional set of rights. Raising my eyes from the index, my eyes lighted once again on St Peter Mancroft, right outside the huge modern windows of The Forum. Here Thomas had been baptised. Here his existence had first been recorded. In trying to do his best to provide for his family Thomas had lost his right to live in his home town and was henceforth banished to a noisy, remote mill two hundred miles distant. My ‘ancient and modern’ photograph now assumed a new significance: loss and injustice. Injustice because the empty promises made to him cost the mill owners nothing, while believing them had cost Thomas and Lucy a great deal.

Sadly the Settlement Examination papers (I referred to this stage of the process in my last post) have not survivied, nor have the equivalent papers for the other end of the process in Fewston. These would have given me a lot more information about dates of migration. However, thanks to this Removal document I now know that Thomas and Lucy first moved to Fewston earlier than previously thought – probably around 1825. I now understand that the Certificates of Settlement were time-limited. As soon as Thomas had acquired legal rights of settlement in Fewston – presumably by being hired continually for more than a year and a day – the certificate ceased to have value. Hiring Thomas may have been risk-free for the owners of the West House Mill, but for Thomas and Lucy it was a one-way ticket. We might imagine that they tried to make it work, but finally were so unhappy that they decided to return to Norwich; and by then it was too late. All previous settlement rights had been erased. On 29th April, 1826, just three months after the Norwich birth of their fourth child, the Removal Order was signed for their forced return to Fewston.

Thomas and Lucy did not go quietly. They were back in St Martin at Oak for the baptism of a fifth child by 1828; in Fewston for the sixth in 1830; possibly (according to a note on the parish accounts) back again briefly in 1831; and in 1832 a final child was baptised in St Martin at Oak. Between 1834 and 1843 six more children were baptised, all at Fewston, and the 1841 census shows them here, living in workers’ accommodation. Thomas, formerly a skilled handloom weaver, is now an ‘engine minder’. The six oldest children, aged twenty to eleven are all ’employed at the flax mill’. I strongly suspect that it was through realisation that this would be the inevitable fate of all their children, and a desire to avoid this, that Lucy and Thomas were so desperate to escape. It is notable, however, that the eventual ‘acceptance of their fate’ coincides with the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, with its central focus on the workhouse in dealing with the poor. Faced with trying to make a go of it in Norwich but the likelihood of the workhouse for the entire family if they failed to do so, Thomas and Lucy seem, reluctantly, to have chosen Fewston. They would now live out their days in Yorkshire, relocating to Leeds by 1846, but my guess is that their hearts remained in Norwich.