One of my great grandfathers, George, was adopted. This was in the 1860s, so it was an informal arrangement and the couple who took him in were his biological father’s older sister and her husband, whose name was Feargus.

Feargus had a middle name: O’Connor; and although I was new to genealogy at the time of discovering all this, I already understood enough to know there was a strong likelihood that this was a maiden name, probably from his mother’s side and probably the two names indicating an Irish connection. However, following back Feargus’s mother’s and father’s lines for a few generations, I could see they were solid Yorkshire stock. No Irish, and no O’Connors. It was a mystery.

The solving of the mystery, when it came, was from a surprising source. But before going onto that, I want to tell you something about Feargus’s parents.

They were nail-makers, and they lived in the village of Hoylandswaine, not far from Barnsley. I found a little book published by the Barnsley Family History Society: The Nail-Makers of Hoylandswaine, collated and compiled by Cynthia Dalton. It includes not only the history of nail-making in Hoylandswaine, but a description of the life, together with potted biographies of the nail-makers recorded in the censuses. I learned that the life of a nail-maker was a hard one. Some had their own forges and worked as a family unit; others rented space in someone else’s forge; and yet more worked for a nail master on his premises.

Click here to see a surviving Hoylandswaine nail forge, now a museum.

Usually, the men started work at 6am, and might keep going until 10pm, with breaks only for meals throughout the day. Pay was low, and since some of the nail masters were also the village shopkeepers or inn-keepers who couldn’t resist squeezing a little extra profit from their workers, payment may have been made in the form of provisions from that other business. Women did the work too, for less money, and alongside taking care of the house and children.

Hoylandswaine nailers go rat-a-tat-tat,

On thin watter porridge, and no’ much o’ that

Anon. (In: Cynthia Dillon: The Nail-Makers of Hoylandswaine)

It seemed a very small life: long hours of repetitive work, isolation, hardship, trapped by low wages and unscrupulous employment practices, and no power to change any of that. I wondered what time was left for enjoyment, or if life was one long slog from beginning to end; and then I set aside Feargus’s family and moved on to other lines.

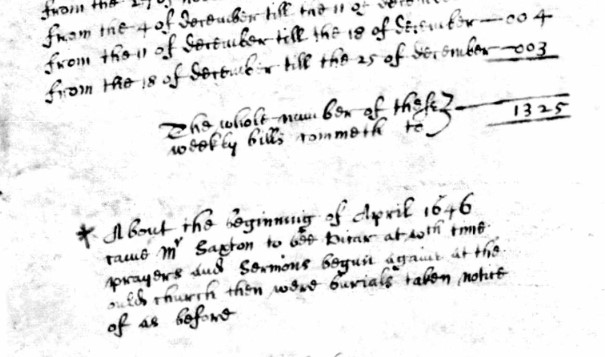

It was years later – early 2019 – when the riddle of Feargus’s Irish connection was solved. It came while I was reading John Waller’s The Real Oliver Twist – the true story of pauper apprentice Robert Blincoe. Part two (p.79) begins with a quote – and I gasped when I saw the name:

‘Scores of poor children, taken from workhouses or kid-napped in the streets of the metropolis, used to be brought down by […] coach to Manchester and slid into a cellar in Mosley Street as if they had been stones or any other inanimate substance.’

Feargus O’Connor (1836)

I looked him up… and realised I had known Feargus O’Connor all along – I learned about him in ‘A’ Level history at school, and in view of the Leeds connection (below) we would have spent some time on him, but my brain had mostly opted to remember the activities of ‘Orator’ Hunt.

Stipple engraving portrait by unknown artist

Source: Wikipedia. This file has been extracted from another file, Public Domain

Feargus Edward O’Connor was an Irish landowner and lawyer, elected as M.P. for Cork in 1832. (Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, so his seat was in Parliament at Westminster.) In 1835 he was re-elected but disqualified on the grounds that he had insufficient property to qualify as an M.P. (although it seems that was not so). It was from this time onwards that he began to agitate for radical reform in England, speaking at rallies and meetings and emerging as the leader of the Chartist cause. He campaigned for the ‘Five Cardinal Points of Radicalism’, which would later be five of the six points embodied in the People’s Charter. In 1837 he founded the radical Northern Star newspaper in Leeds; and then in 1840 was arrested for sedition, serving fifteen months in York Castle gaol.

1840 was the year my adoptive great great grandfather was born. His parents’ choice of name – Feargus O’Connor Heppenstall – speaks volumes. It turns out they did know the conditions in which they were working were unjust. They could imagine a better life. And what’s more, they knew of developments throughout the country and the movement for change; and through the work of Feargus O’Connor, they saw a way to achieve that. It turns out their lives were not so little after all. They were fighting for a better world at a time when that was much-needed; and I am proud of them.

In fact my tale is awash with Feargus O’Connors, all of them in Leeds. As a young man my adoptive great great grandfather Feargus made his way to Leeds and became a butcher. His adopted son, my great grandfather George, would go on to name his own first son Feargus O’Connor Heppenstall too, although I don’t think George was a political man, and believe this was a tribute to the man he considered his father rather than to the Chartist leader.

The original Feargus O’Connor was not a man without controversy. Undoubtedly charismatic, he was admired for his energy and powerful oratory, but also criticised for advocating physical force if necessary in order to achieve his goal of universal male suffrage. In this, he went further than the moderate line taken by other Chartists.

I was reminded of all this last week, while watching videos recorded by experts for All About That Place. One such expert was Mark Crail, who has a website and a blog about Chartist Ancestors, as well as a separate website about Trade Union Ancestors. There is also a page dedicated to the Six Points of the People’s Charter. Some of the articles focus on Chartism in different parts of the country; some on leaders. There are quite a few blog posts dedicated to Feargus O’Connor’s life and work. If your ancestors were in the industrial heartlands during the nineteenth century, or if you know they were active in the Trade Union movement, you might be interested to explore these sites.

This is what I love about family history. The most ordinary seeming people can have surprising stories to tell if you delve a little deeper. It is through these stories that we can learn about the lived experiences of people in different places, classes and at different times throughout our history.