In March I wrote about the additional layers to ‘geography’ that genealogists and historians have to be aware of. Today’s post builds on that, looking at how we might record information about places on our family trees in a way that makes sense not only for the logical flow of information about a person’s life, but also to the algorithms of any website we’re using to build our family tree.

The following are my own thoughts on this. How you choose to record places on your own tree is a matter for personal preference. My ideas are also based on personal experience of what works best when working with my online tree at Ancestry.co.uk. but the issues that inform this are not restricted to the Ancestry website, so if you have an online tree somewhere else some of the issues might be the same, others quite different. The point is to develop a system that works for you, based on good practice but also one that the particular website’s search engine understands.

On Ancestry, there are two ways of adding new information/ ‘event’s to our tree. The first is by following Hints, by a Search from that profile page, or by starting a Search from the top menu bar. The second is when we enter new life events that we’ve located from different sources. Although we’re more likely to move onto this method as we progress, we’ll start here by looking at this first, because it’s here that we really need to think about what information the different ‘fields’, including specifically here, the Location field, are asking for.

Entering ‘Location’ information on a new life event

There are all kinds of reasons why you might be entering information yourself, rather than linking from information offered up to you by the website. Here are some examples:

- You went to a cemetery and found a gravestone with dates and additional family members

- You’re entering information from a family Bible, or from original Birth/ Marriage/ Death certificates or other special documents or artefacts handed down within your family

- You found information on another website: genealogy website, Family History Society, newspaper archive, etc

- You went to the local Record Office and found a record that relates to your ancestors, such as a Settlement Hearing

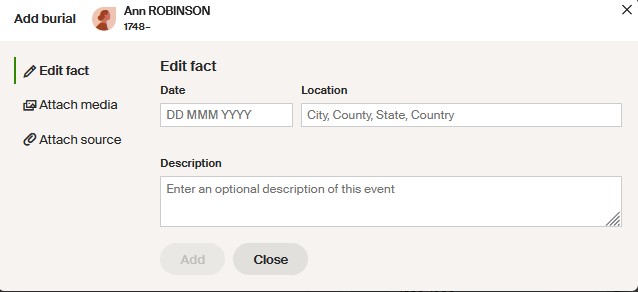

On Ancestry, to enter this kind of information, we click Add above the list of Life Events on the person’s profile page. A pop-up box appears: Add fact or event, with a list of life events to choose from, or you can make your own ‘Custom Event’.

Now we must fill in all the fields ourselves. Having to do this really makes us think about what the issues are, and why this may not be as straightforward as it might seem. Remember that in this post we’re just thinking about the Location.

In the pop-up box above, the words ‘City, County, State, Country’ is our hint as to how to arrange our place name. Of course, that’s based on the USA rather than UK, where we don’t have separate ‘states’.

Write place names as they are on the record, not what would be correct today

For example, today, Brighton is in East Sussex, but historically was in Sussex. We should input the county as it is on the record, which before 1974 would have been Sussex. Similarly, Gisburn was in the West Riding of Yorkshire, but since 1974 has been in Lancashire, so a 1980 birth should be recorded in Lancashire; a birth in the same house in 1970 would be recorded as Yorkshire. Some of the newer counties didn’t even exist when the record was created. For example, Wolverhampton, now in the ‘West Midlands’, was formerly in Staffordshire.

The further back we go, there may be even more archaic county names, for example, the Isle of Wight was in ‘the County of Southampton’. These ancient counties don’t work with Ancestry. I always record this as ‘Hampshire’, but would use the description box (see image above) to record that ‘the County of Southampton’ was given on the record.

Use official place descriptions, not ‘the way we referred to it in our family’

When I was little I used to write to my great uncle who lived in a village called Methley, about ten miles from Leeds. My mother showed me how to write the address as ‘Methley, nr. Leeds, Yorkshire’. When I started my family tree it seemed important to me to preserve this memory, so I wrote ‘Methley, nr. Leeds, Yorkshire’ for the location of that great uncle. This was my family history, after all! I also referenced every incidence of the main church in Leeds as ‘Leeds Parish Church’, that being how it was referred to locally. Sadly, algorithms don’t understand our happy memories! We can still include this information, but put it in the little box for ‘description of this event’ rather than in the ‘Location’ field.

When entering residence, limit this to the place, not the actual street address

If you include the full address in the location, forever more when you write the place name, Ancestry will offer up every single address you’ve ever written in that location for you to select. Below, here’s what happens every time I write ‘Hunslet’. You can still write the full address if that’s the way you want to do it, but it’s better to put it in the Description box linked to the event.

Recording church names for baptisms, marriages and burials

One of my ancestors was baptised at St Leonard’s church in Bilston, Staffordshire. If I write this information in the Location box on Ancestry, this could be confused with the town called St Leonards, which is in East Sussex. Similarly, St Helen’s church could be confused with the town of that name in Merseyside; St David’s after the Welsh city, and so on. For this reason I always put the placename first, then the church: Bilston, St Leonard, Staffordshire, England. Usually, I only include the church name when recording religious rites that took place within the church.

Recording the historic parish name in cities of multiple parishes

There is an important exception to the last sentence in my above ‘rule’. In larger historic towns and cities that developed around the 11th Century there tended to be many small parishes within the walls, and since the Anglican parish was also the administrative unit for secular administration, it’s useful to record this parish information for all events. I wrote about this previously, using Norwich as an example. There, prior to the introduction of Civil Births, Marriages and Deaths in 1837, I would record a birthplace and place of death like this: ‘Norwich, St Martin at Oak, Norfolk, England’. It is true and accurate, and it gives us additional information about where, precisely, in Norwich, the event occurred. The same applies for London, Winchester, York, and other historic towns.

When recording the Registration District doesn’t tell the true story

Since 1837, Civil Births, Marriages and Deaths are recorded within Registration Districts. You’ll find a list of every single Registration District (RD) that has existed since then on the UKBMD website [here]. Often, these make perfect sense. For example, a birth between 1837 and 1998 in the Wiltshire town of Devizes will have been registered in the RD of Devizes. However, as the UKBMD page for the Devizes RD shows, many other settlements in the area came within its boundaries. So if your ancestor was baptised in Pewsey, 11 miles to the east of Devizes but registered in Devizes, what location do you record for the birth? What if you also know from subsequent censuses that your ancestor was in fact born in the village of Sharcott that lies within the ancient parish of Pewsey? Which one would you record as this person’s place of birth? This is what I would do:

- Record the birth as the actual village if I know it, but also add the General Register Office reference in the description box. This includes the RD of Devizes. e.g. Name xxx; Mother’s Maiden Name xxx; GRO Reference: 1837 D Quarter in DEVIZES IN THE COUNTY OF WILTS Volume 08 Page 250

- Record the baptism with the name of the parish church in Pewsey.

Remember to add county and country

As you can see from my ‘Hunslet’ example, above, I didn’t always do this when I was starting out, and am still plagued by the fact!

The problem with simply writing the town or city is that many places in the New World settled by British migrants were given the names of former hometowns of the settlers. See what happens when I just type ‘Portland’.

In future searches, the search engine doesn’t know if we mean Portland in Dorset or one of these other Portlands, and may offer up all kinds of unrelated records.

If, instead, we consistently record the county and country, it helps the search engine and also helps us to keep our research tidy, enabling us to see at a glance where the person was.

If you’re an old hand at this family history research, all this is nothing new to you – but if so, please do share any examples from your own research, showing how you dealt with an unusual location situation. If you’re fairly new to researching your own family tree, I’m guessing you never knew there could be so much to recording someone’s ‘location’!

Linking a new event after searching on Ancestry

Most of the above points apply to building your own tree, whatever application you’re using to record the information. Let’s move on now to how information gets added to our trees when we’ve done a search on the Ancestry website. If you’re using a different subscription website for your tree the process will be different but the same issues may apply.

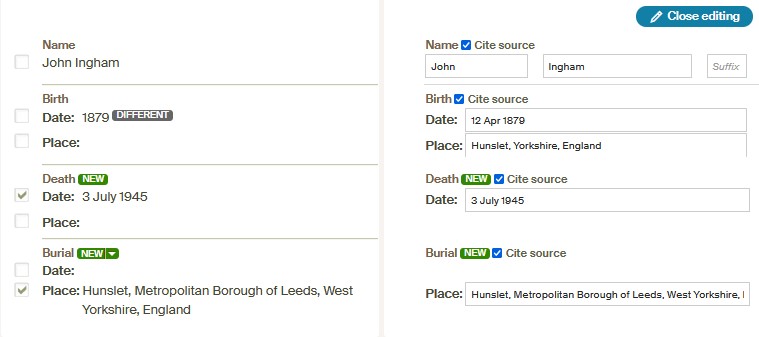

If we search for records from the person’s profile page, or by following a ‘Hint’, or by filling in details on the general search pages, when we find a record we want to add to our person’s profile page, the information fields will already be completed. This information is based on someone else’s transcription of the record, and how it was indexed. Here’s an example:

In this box information I already had, and new information, are separated out. Any differences between the two are highlighted. We can edit, accept or decline any changes to existing information. In the above example I decided to accept it as it is (although I can see a problem), and now, on this person’s profile page, if I click on the entry for his burial, I get a similar pop-up box as the one at the top of this post, but with some of the facts filled in – actually in this case, just the location:

The problem here is that the location for this record is not indexed in a way the Ancestry algorithms will understand. Hunslet is good. Leeds is sufficient without the ‘Metropolitan Borough of’ part (although I would not necessarily include ‘Leeds’). West Yorkshire did not exist in 1945; it is a county level authority that was created in 1974, so the county should just be ‘Yorkshire’. Although the country is the United Kingdom, since the law and administrative arrangements are different in Scotland and Northern Ireland, in ancestry research we usually just refer to England, Northern Ireland, Scotland or Wales, therefore the country here is England (which you can’t see because of the length of the location information) and is correct on this record. For me, this location should simply be ‘Hunslet, Yorkshire, England’, or ‘Hunslet, Leeds, Yorkshire, England’, and that is how I would amend it.

Yorkshire ‘Ridings’

Some of the old Yorkshire records include the ‘Riding’ in the indexing. Unfortunately, Ancestry cannot cope with this at all. If we leave it in, the record entry will forever default to Riding in Northumberland – a place I cannot find on the map, but which has definitely caused me some problems over the years. So my advice is to remove any reference to the Riding from old Yorkshire records. If you want to include the Riding, do it in the ‘Description’ box attached to the Event.

Be vigilant!

The lesson here is that just because information is presented to you in a certain way, does not mean it is correct, and does not even mean it is algorithm-friendly on that website! If we have our own sense of what is needed for recording the location – what we personally would like, and what we have come to understand the website requires – we can record information more consistently, more correctly and in a manner that makes future Hints and Searches more effective.

I hope you’ve found something useful in all this.