You might have noticed I’ve given a lot of thought on this blog to records related to our ancestors’ deaths. It started a couple of years ago when an increase in the cost of civil BMDs prompted me to write about what other kinds of records might be available that would give much of the same information – and sometimes more – thereby saving the cost of the death certificate. Next came What Can Death Records Tell Us About Life? Death records have also featured here and there as evidence used in conjunction with other findings in my research to prove one hypothesis or another. The truth is I love a good death record. They can tell us SO much about a person, their life and family; and none more so than a Will.

The last two posts have focused on how to find Wills and Administration documents, both since 1858 and the far more cumbersome arrangements before the changes of that year. Today we’ll look at lots of ways we can use the Wills, particularly those from earlier centuries when there might be gaps in other record sets. They really are not just about how much money there was and who inherited it!

A Will can…

Substitute for a baptism

There was an example of this in a recent post when, finally, I found a father’s will in which he (Nathaniel) named and bequeathed land to my 6xG grandmother Jane, who I had long suspected was his daughter. Until this point I had built a good case but there was no definite evidence that they were father and daughter. Although, in the absence of a baptism record, I still have no definite birth year for Jane, the order in which Nathaniel refers to his two daughters indicates she is younger than her sister (baptised 1685), thereby supporting Jane’s own death record which suggests a birth year of 1687.

In another example, I suspected my 8xG grandfather, Thomas, was one of six siblings born to Christopher Simonson. I had baptisms for most of these siblings but not for Thomas, likely born during the Interregnum. In this example it was one of the brothers, Lister, baptised as son of Christopher in 1642, whose Will came to the rescue. In it, Lister specifically refers to ‘my brother, Thomas’. Thomas is a witness, scribe and co-executor to the Will, and by comparing handwriting to other known documents I can see this is definitely my Thomas.

Substitute for a marriage

Lister’s will worked overtime for me. In referencing his brother-in-law, Thomas Snell, he also made his will stand in for his own missing marriage record. Thomas Snell was his wife’s brother, therefore her maiden name was also Snell.

Substitute for a burial

It goes without saying that if Probate has been granted the testator has died! So even if we can’t find a burial record, we have a pretty good idea of the month and place of death. Sometimes the actual date of death is noted on the back of the bundle of papers.

Help you fill out the family of your ancestor

It may name sons, daughters, siblings, parents, cousins… There may also be people who seem to be family members but can’t yet be placed. All need to be noted and when possible can be inserted into your tree.

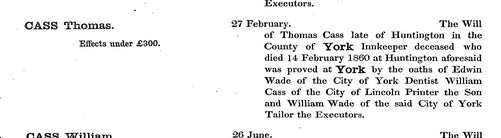

However, the absence of a child’s name does not imply a parting of the ways. Nor will the list of children necessarily include them all. A couple of years ago I wrote about my discovery that my 4xG grandfather John Wade’s Will made no reference at all to his daughters, leaving the family business and money only to his sons. The four sisters remained unmarried and lived together throughout their lives. It wasn’t until I obtained each of their Wills that I realised they had been well-cared for prior to their father’s death, in the form of railway stocks and shares. Father John’s arrangement ensured the daughters would retain their own money (and a level of independence) even if they married, while the family business would remain in the hands of his own sons.

Generally, though, wives and daughters will be named – offering us a rare sighting of the female family members in a time when documents usually omitted them completely.

Confirm family roots within a locality

Again, Lister gives value. In his Will he expresses his wish to be buried in the local churchyard, ‘as near to my Ancestors as possible’. This implies several previous generations in this parish. When I first read this I knew only of the father, and baptisms of the other siblings showed he had moved around the region. I now have two more generations before that, and ongoing wider research suggests a long association of this family with the area, although I’m yet to join the dots.

Suggest literacy levels

Although the shaky initials or ‘mark’ of the testator doesn’t necessarily mean they are unable to write (they may simply have been too weak to write at that precise time), certainly we can see which of the witnesses could write. Even official copies of Wills record who signed and who made marks. However originals provide additional clues: By comparing handwriting within the document and with others, you may even be able to work out if one of your ancestors wrote the document – even if maybe they could read and write in Latin.

Provide an insight into family relations

Generally, there is a sense of community at the time of writing and witnessing the Last Will and Testament of a sick relation. Death was part of life, and helping a family member or friend to put his affairs in order and ensure each other’s families were cared for was something done willingly. There is trust evident between the testator and those he chooses as his executors, or to assist a surviving spouse in the task. Occasionally, though, we might pick up on family tensions. In 1684 as my 8xG grandfather John Wilson divided up his lands and property between his five surviving sons, he included this final sentence: ‘And if any of my sayd sons their Executors or adm[inistrators] shall sue Molest or Trouble my sayd Executor for any greater Summe or Legacie then is given them by this my last Will and Testament that then the Legacie to them hereby given to bee voyd and noe more paid to them but Twelve pence.’ It seems John didn’t entirely trust his sons to behave well towards each other.

Hint at the testator’s religious views

Wills can, but do not necessarily reflect the testator’s religious views. They might instead reveal the scribe’s views. Alternatively, I have compared wills written within five years of each other but 40 miles apart, in which the similarity of overblown religious phrases in the opening lines suggests the two scribes were writing to an accepted formula.

Reveal how our ancestors lived

From 1530 to 1782 one of the probate/ administration requirements was that the executor should appoint three or four local men to value the deceased’s personal estate, and provide the probate court with a full ‘Inventory’: a detailed list of every single item of the deceased’s possessions, together with an assessed value for each. The Inventory relates only to the personal estate, i.e. it doesn’t include land and property; but since the list is generally organised room by room, including items found in outbuildings and barns, etc, it does indicate where the household included such buildings, how many living rooms and bedchambers and so on.

In the Will itself your ancestor may list houses, messuages, lands, etc. Comparison with contemporary maps may reveal exact locations of named holdings. He may also identify himself by occupation or standing. Not only does all this suggest a certain standard of living, but it may be compared with other record sets, such as occupations on baptisms or number of hearths listed on the Hearth Tax returns.

Show community networks

Occasionally we will find ourselves reading so many Wills from a small village that we recognise names of all those who regularly help out as scribes, witnesses, executors, takers of the inventories, and so on. We almost start to feel like we know all these 17th century inhabitants who were trusted community members and friends of our ancestors.

And finally… the bit we always expected the Will to be about:

Indicate how the land, property, goods and chattels were to be apportioned

Here we see how land was passed on according to the wishes of the testator and inheritance norms. We start to understand how, where the oldest son inherits the lion’s share, younger sons move progressively down the social hierarchy. There is also the possibility of bequests of small items treasured by the testator to a special person. (How wonderful would it be to recognise an item that your family still has!)

Alas…

Sadly, sometimes the bequests in the Will and the named beneficiaries prove you haven’t got the right person. I bought the Will of what I assumed was my 7xG grandfather Robert Lucas. He had a son named James in exactly the right place and at the right time to be my known 6xG grandfather, but when I read the Will there was no mention of James, just two daughters. It sent me back to the parish registers, and I found the little James I had assumed to be my ancestor had died not long after birth.

*****

Although most of the Wills are written in English, the further back you go, the more likely it is that you’ll need to be able to read old handwriting, but I think you’ll agree that with such riches available from scouring them, it’s worth the effort.

These are all examples of things I have learned from looking at Wills. Can you add anything more? Has something astonishing in an old Will ever helped you to break down a brick wall or make a great discovery?