Family stories are not always true, but often there is truth in them.

I wrote in my last post about my elusive GG grandfather Edward Robinson. Last month, after a 25-year search, I was finally able to place him with his birth family. Throughout the search there had always been at the back of my mind my mother’s story – which must have had its origins with her own grandmother, Edward’s daughter Jane. The story was that when Jane’s mother died, after spending all his money on women and drink Edward went back to The Crooked Billet where he was born, and threw himself in the river. I knew The Crooked Billet, still a pub until fairly recently, and although I never went inside, whenever I drove past I would think of its connection to my family history.

Even with a one-line story such as this there may be several elements. I had long ago found evidence to show that my GG grandmother, did indeed die long before Edward – thirty years earlier to be precise. I had also found several drunk and disorderly charges, each resulting in several nights in Wakefield prison. What surprised me when I first researched Edward was that there was another long-term partner after my GG grandmother. Edward was with Hannah at least seventeen years, from before the 1881 census until his death in 1898. This was never passed down in the story. And finally, Edward’s act of suicide and the location is evidenced by his death certificate and the Coroner’s notes.

Only one element of this story remained to be proven: that Edward was born close by The Crooked Billet inn in Hunslet. Throughout the years of my search for Edward’s birth family I remained guided by this, but always open to the possibility it might not be accurate.

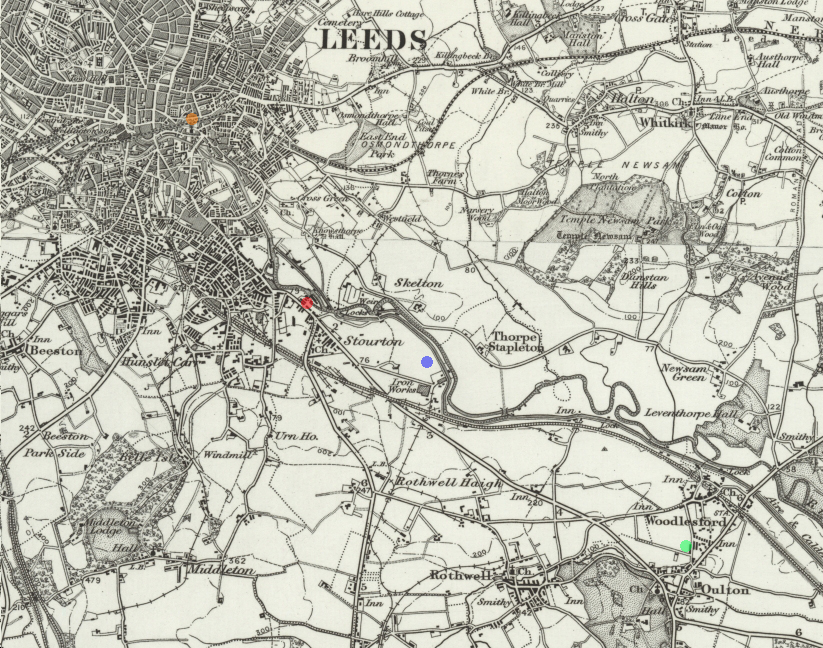

I now know that on his father’s side Edward is descended from generations of Edward and John Robinsons, all living in Hunslet in Meadow Lane, just across the river from Leeds township and marked on the map below with a blue dot. Edward’s family lived here at the time of his sister Elizabeth’s baptism 1822. They also, it turns out, had an older son, John, baptised in 1818, Meadow Lane being the place of residence given here too. At some point between sister Elizabeth’s birth in 1822 and brother John’s death in 1834 Edward sr. broke with tradition and moved with his family to Pottery Fields, marked on the map with a pink dot. The Crooked Billet inn was more than a mile away in Thwaite Gate, indicated with a red dot, right on the border with the parish of Rothwell. It isn’t looking like Edward would have been born there.

It is in fact Edward’s mother, Elizabeth Clarebrough’s family that is key to this puzzle. I’ve now traced her line back to my 11xG grandparents in the sixteenth century. The Clarebroughs are a long-established Rothwell family, located mainly in the Oulton and Woodlesford area. Elizabeth and her twin sister were eighth and ninth of thirteen children, although at least three of them did not survive to adulthood. Baptism and burial records indicate that the family relocated from Oulton between January and August 1791. The place they moved to was… Thwaite Gate in Hunslet, the exact location of The Crooked Billet. They were still there in 1805 when Elizabeth’s father was buried, and although by the time of Elizabeth’s mother’s death in 1830 she was living in Woodhouse Hill (indicated on the map with a green dot), she would seem to have remained close by the area around Thwaite. Even if a baptism record does somewhere exist for my GG grandfather Edward, the abode given will be the usual residence – Meadow Lane or Pottery Fields – and yet it is entirely reasonable to consider that his mother Elizabeth might have gone to stay with her own mother for the period of her confinement, and that he really was born right next to or at least close by The Crooked Billet.

Thinking more widely than this story for a moment – I wonder if this might sometimes be the key to locating missing baptisms? What if our ‘baptism-less’ ancestors who insist on census records that they were born in place X really were born there, because the mother had gone to be with her own mother for the birth, even though a baptism record will be found in place Y…? After all, the parish register records the name and abode of the father, not the actual place of birth. Quite apart from a truthful response to the question of the father’s own abode, it was in any case important for proof of settlement for a child to be registered in the correct parish.

Back to Edward, we can now fast forward to March 1898 when, the story goes, he left his home in Leeds township (marked orange on the map below) and drowned himself in the water by The Crooked Billet (red dot). In fact, thanks to several witnesses whose words are recorded in the Coroner’s notebooks, we can be more precise than that. South of Leeds the river Aire, being not fully navigable, is accompanied on its way to the Humber by the Aire & Calder Navigation canal. The Coroner’s notes, written the day after Edward’s death, evidence that Edward had walked along the water from Thwaite Gate in Hunslet and thrown himself in the canal close to Rothwell Haigh, at roughly the spot marked by the blue dot. Knowing what I know now about his mother’s origins, just a little further along the river, in and around Woodlesford and Oulton (green dot), knowing that as a twin her family’s connection to her sister and her children might have been particularly close, and knowing through burial records that the older generation retained a strong connection to the parish of Rothwell even after moving to Hunslet, I can imagine happy childhood days playing by the water, or walking the three miles or so along the water to visit family.

Of all my ancestors, Edward has been the hardest to love. Finally, working through his story with the additional information, and re-reading the Coroner’s notes, has helped me to make my peace with him. My impression of Edward was that he didn’t have a good life. He didn’t settle to a trade, and the deaths of two significant women in his life – his mother and his first wife, seem to have sent him off on self-destructive behaviour. My mother’s story, suggesting that in his despair, Edward was returning to his own roots to drown himself, was certainly true, but I now believe the attraction was not The Crooked Billet inn itself, but happy childhood memories with his mother and family by the water on the way to Rothwell.

*****

I’ll be taking a break from the blog for a few weeks. My next post will publish on 15th July.