I’ve spent a lot of time, in recent weeks, analysing the baptism, marriage and burial registers of Leeds in the 17th century.

All English genealogists working at intermediate level and beyond know about ‘the Interregnum’ – the period from the execution of Charles I in 1649 to the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 – and the devastating impact this can have on tracing back generations who might have been baptised, married or buried during this period. But have you ever looked at the parish registers of your parishes of interest to see how such events played out on a more general basis in the records being kept?

Before starting this particular research I contacted the local archives and was told the registers for Leeds were complete. I then started to investigate the period more fully, through background reading, and found that the Interregnum was just one of a whole series of contemporary social and political factors impacting on the town.

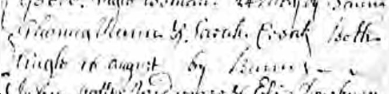

First, Leeds had both economical and tactical significance in the English Civil War, which began in 1642. The Battle of Leeds took place on 23 January 1643, and while the parish burial register indicates relatively few deaths, the vicar of Leeds was forced to flee the town.

Two years later, an outbreak of the plague wiped out one fifth of the population of the township. The overcrowded, close-built housing, and particularly that on lower ground by the river and becks (streams) where fulling and dyehouses, and housing for the humbler clothworkers were situated, was perfect breeding ground for the disease. In March 1645/46 the situation was so serious that the parish church was closed, and no religious rites performed there for some weeks.

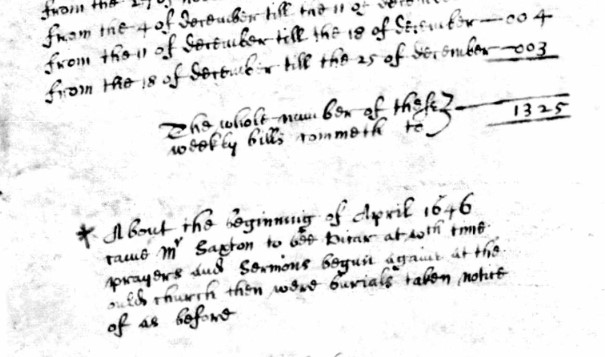

‘About the beginning of April 1646

came Mr Saxton to the vicar at w[hi]ch time

prayers and sermons begun againe at the

ould church then were burials taken notice of as before’

If you have a subscription with Ancestry you can see the whole of this page, and the notes on the preceding page [here].

Next came the Interregnum, which lasted from January 1649 until May 1660. During this period the church was effectively disestablished. Moderate Anglican clergy were replaced with those of Puritan persuasion. Custody of the parish registers was removed from the ministers and given to civil parish clerks, and solemnisation of the marriage ceremony became an entirely civil function. Bishops (and hence Bishop’s Transcripts) were abolished, and although records were kept they were often badly organised. When Restoration came in 1660, and the role of the church returned to its pre-Interregnum position, vicars often refused to accept the validity of records handed to them by the secular clerks.

In a practical sense baptisms did continue, but it seems the previous arrangements for local chapelries to report names of those baptised to the main parish church collapsed.

‘The most of the children baptized at the several chappelles

in this parrish for this last yeare, are not to bee found in this

book, because their careles parents neglected to bring in their

names, and therefore let the children or such as want the names

hereafter blame them, who have beene often admonished of it and

neglected it’

If you have a subscription with Ancestry you can see this note in situ [here].

Simlarly – and note that this is the same hand as above – the recording of marriages brought about much displeasure:

‘Those that come hereafter to search about Registering of marriages

from the 8 of June last until this present 11 of October 1659 may

take notice that the persons married within that time took the liberty

either to marry without publishing as many did or else they went to Mr

Browne Curate of the ould church and got married there and at

several chappels in the parrish without ever acquainting the Registrer

or paying him his Dues, and therefore if any occasion fall out to make

search for such they may judge who is to blame. those and many others before took the same liberty

October 1659′

If you have a subscription with Ancestry you can see this note in situ [here].

More strife followed with religious division, and persecution interspersed with periods of greater tolerance. The population of Leeds was largely split down the middle in terms of traditional Anglican and adherents of a more hellfire-and-brimstone approach to the scriptures. This, too, meant that at various times ardent Royalist or committed Puritan ministers in turn were ejected from the church, bringing about further disruption in the registers.

As a consequence of the above, although in terms of coverage of years it is true that the Leeds parish registers have no gaps, in terms of the content of those years, not only are there significant gaps, but also (as you can see in the two images directly above) the uniform, neat handwriting of the Interregnum years belie the fact that these are the church clerk’s later transcriptions of the contemporary notes formerly made by the civil parish clerk. (And we all know that transcriptions may include errors and omissions.)

Even when working in later periods, when faced with a selection of potential records that don’t quite fit, it’s important to remember that record sets may be incomplete. Records may have been lost or damaged, may not be available online, may have been mis-transcribed and indexed, or may never have existed – sometimes through clerical error at the time and sometimes because of an issue of wider application such as those outlined above. It has been fascinating to read about these events in textbooks and then see for myself the impact on the registers, but also sad to realise that some of those life events that failed to make it onto the parish registers may have been my own missing ancestors.

If you’d like to try this for yourself

I’ve found the easiest way to browse record sets (whether that be to examine them line-by-line in search of an ancestor, or to browse them looking for the impact of historical events as I have used them above) is on Ancestry, and the easiest ‘way in’ to browse any parish register is to go to an existing record for any ancestor from that record set (already in my online tree) and then use the links at the top of the page to go to the exact parish and year I want. In the example below, the record set is for the whole of West Yorkshire for the period 1512-1812. If I click on ‘Rothwell, Holy Trinity’ I can select any other parish I need from the drop-down menu. Then if I click on the year I can change that to the one I want. From that point I can browse the whole year of baptisms, marriages or burials for the parish. After a while you can easily work out roughly where the marriages or the burials start, and go straight to the appropriate pages for each year. Obviously this will only work for you if Ancestry have a licence with the relevant archives for your parish of interest.

On FindMyPast, if records from your parish of interest are on there, you can move backwards and forwards from any page for a record you already have, but this is cumbersome, and there’s no way of knowing how many more pages remain of the year you’re currently looking at before you’ll get on to the following year. However, some of the record sets are ‘browsable’, and this is an altogether better experience but not all record sets are available yet to browse in this way. The difference is that ‘browsable’ sets have a ‘filmstrip’ facility (see bottom left on image below) which you can click to open, and then whiz back and forth along the pages, quickly homing in on the pages you want.

To find these browsable record sets, select ‘Search’ from the upper menu bar, and then ‘All Record Sets’. Type ‘browse’ in the upper left hand box, and you’ll see the numbers of records reduce to just those collections that are browsable. Then, in the box below, select ‘England’, and finally type in your place of interest. I entered ‘Norfolk, England’, and from the 50 record collections available I selected ‘Norfolk Parish Registers Browse’. On the next page you enter a year range (or leave it blank) and an event (baptism, marriage, etc) or leave it blank, and then the parish. I haven’t yet found any records of interest to me that are browsable, but this will be a good facility when more are added – and you might be luckier than me.

On FamilySearch (free to use, you just need to register for an account) a huge number of images are available to browse, but not all parishes are covered, and even if your parish is, there may be gaps. To find them, from the upper menu bar, click ‘Search’, then ‘Images’. On the next page type in the name of your parish. I tried several of my parishes of interest before finding one for which images were available: Great Yarmouth in Norfolk. It may ask you to select from a few options, and then click ‘Search Image Groups’. On the next page you’ll see precisely what they have. For Great Yarmouth it was just marriage registers, with an almost complete coverage from 1794-1899, but some gaps.

It would be great to hear if you have any successes with this. Have you come across a significant event in your town and then verified it through parish records?