This is the last post in my 3-part mini-series about using chromosome browsers in genetic genealogy. You’ll find links to all my previous DNA posts [here].

Today we’re talking about GEDmatch: an online service that allows you to upload your autosomal DNA data files from any of the testing companies and compare with people who have tested with different companies. In other words, you’re not restricted to just comparing your Ancestry results with other Ancestry matches or your MyHeritage results with others who tested there: you can compare common matches with all the testing companies in one go.

Alongside this they also have a number of tools to help with analysis of these comparisons. The basic package of tools is free to use. These include a chromosome browser, which is particularly useful if you tested with Ancestry, since they don’t provide one. There are more advanced tools (called ‘Tier 1’), but there is a monthly fee to use them, currently US$10 per month. You can subscribe just for one month at a time when you know you’ll have plenty of time to explore.

GEDmatch doesn’t itself offer DNA tests. They state that when you upload your data, the information is encoded, and the raw file deleted. Even so, we should all always check Terms & Conditions when we upload our DNA data to any site, and be sure we’re happy.

Often people who upload to GEDmatch don’t know what to do next; and I know both from personal experience, and from discussion with my own DNA cousins, that at first sight it all seems pretty daunting. So in this post I’ll talk you through what I consider to be the essential basic tools. Once you’ve uploaded your DNA files you’ll find links to all these on your home page at GEDmatch, in the right hand sidebar:

All you need to make use of these tools is the kit number you’ll see on the left hand side under ‘Your DNA Resources’. It starts with one or more letters followed by some numbers. Copy that and then follow these links:

One-to-many DNA comparison

Click on the second ‘One-To-Many’ option, and on the new page that appears, paste your kit number in the box and click to display your results. What you’ll get is a list of everyone on GEDmatch who matches you. They are arranged in descending order of the size of your match.

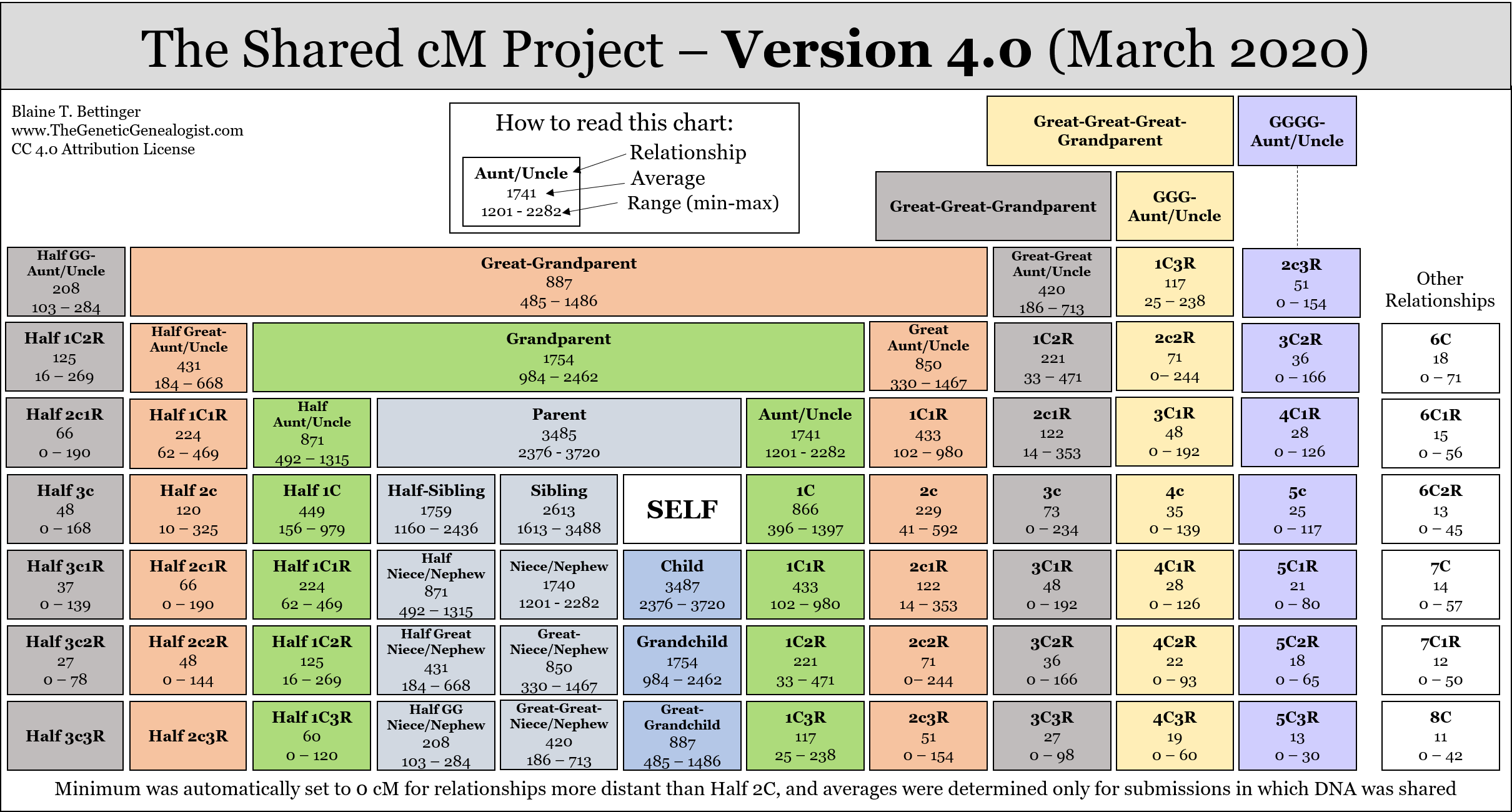

Looking from left to right you’ll see your matches’ kit number, name or pseudonym, email, largest segment and total cM (this is the field by which the matches are arranged in decending order), likely number of generations to Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA) and some other information. You might already recognise some of these people and be able to place them on your tree, together with your MRCA.

Now we’ll move onto finding out more about some of these matches. So pick the top one or another one near the top, and copy their kit number. Then back at your GEDmatch home page, click on:

One-to-one Autosomal Comparison

Paste your own kit number in box 1 and your selected match’s kit number in box 2. (Hint: after you’ve pasted your own number once you can bring it up again by double clicking on box 1, so on subsequent searches you’ll only need to input your match’s kit number.)

For these early searches leave the rest of this form in the default settings. You can play around with them and learn more later. Click compare.

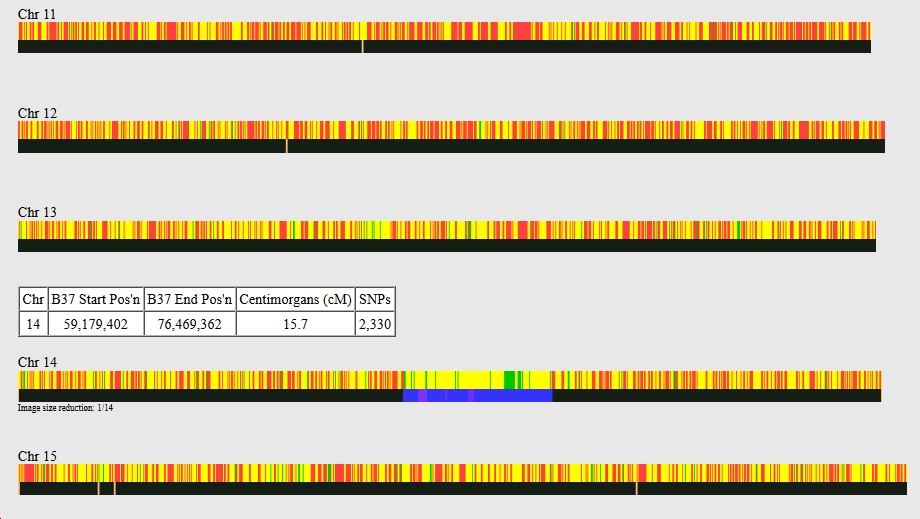

What you’ll get on the next page is a chromosome browser showing exactly where you and this person match. For every chromosome with a matching segment you’ll also see a little box, showing start and end position of the segment and number of centimorgans (cM). The image below shows just part of one of my match comparisons – Chromosomes 11 to 15. As you can see, this person and I have a matching segment on Chromosome 14.

If you’re painting to DNA Painter, as described in my last post, this text in the little box is the information you need to paste to ‘paint’ the segments. If you match on more than one chromosome you can go back to the input form and change ‘Graphics and Positions’ to ‘Position’ only. This will remove the chromosome browser from the results and simply provide you with several little boxes of information that you can then copy all in one go.

Now, keeping those same two kit numbers, return to the home page and click on:

People who match both, or 1 of 2 kits

Again, enter your own number for kit 1 and your match’s for kit 2.

What you get this time is three lists:

- people who match BOTH of you

- people who match just you

- people who match just kit 2, and not you.

It’s the list of people matching both of you that’s most obviously helpful. If you can already place any of these shared matches this may help you to narrow down the part of your tree where you and this person have common ancestors. However, thinking back to my previous post on chromosome browsers, matching a third person does not necessarily mean you all ‘triangulate’. Certainly you share a common ancestor with each one, but it’s possible that the common ancestor they share with each other might be on a different line, not related to you at all.

If you’ve read my previous DNA posts or if you’ve already been using MyHeritage, you’ll see that this basic package of tools on GEDmatch is not dissimilar to the tools on there. The One-to Many comparison equates to the MyHeritage DNA match list; The One-to-One autosomal comparison equates to MyHeritage’s chromosome browser; and the People who match both, or 1 of 2 kits roughly equates to the shared matches you see when you click to Review any of your matches. The advantage of GEDmatch is that there is no fee to use these tools. There is also the availability of the more powerful ‘Tier 1′ tools when you want to make use of them. MyHeritage, on the other hand, combines all of their tools with availability of matches’ trees that you can compare with your own. Plus they have the triangulation tool discussed two posts back. In terms of enjoyment of use I would have to say I prefer MyHeritage’s DNA offering above all others, but GEDmatch is a powerful additional tool in your DNA toolkit, not least because not everyone has tested with/ uploaded their data to MyHeritage, and because of the availability of the Tier 1 when you feel ready to move on.

*****

My DNA posts are intended as a beginners’ guide, building up the information in order, in bite-sized chunks. Click [here] to see them all in the order of publication.

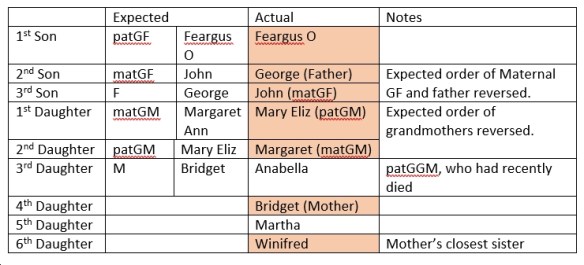

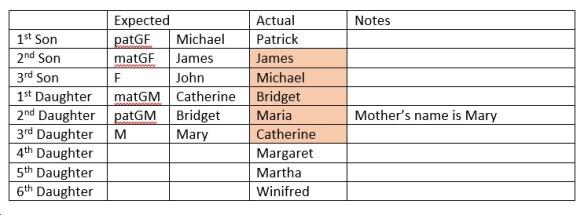

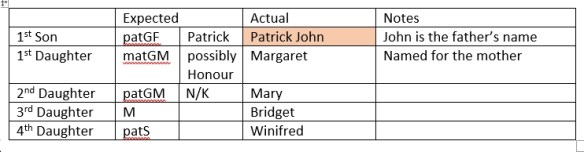

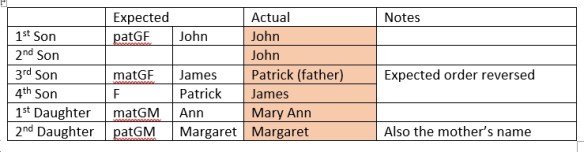

With only two slight deviations Patrick and Margaret did it by the book: their first son died before a second was born. They therefore re-used the paternal grandfather’s name for their second son. They also reversed the expected order of father and maternal grandfather.

With only two slight deviations Patrick and Margaret did it by the book: their first son died before a second was born. They therefore re-used the paternal grandfather’s name for their second son. They also reversed the expected order of father and maternal grandfather.