My last post focused on the potential dangers of relying on transcriptions. But transcripts can also be our friend! Today we’ll focus on their benefits, and how to make the most of them. I hope there is something here for both beginners and intermediate level family researchers. Perhaps beginners will benefit most simply from an appreciation of the variety of records available, whereas intermediate level genealogists will be more interested in wringing every last drop of use out of each of them.

To start, then, what do we mean by ‘transcription’?

In my last post I used the term as a sort of ‘catch-all’ for documents that copy and record the information from an original document. But in genealogy there are lots of different kinds of record that do this, and some of these copies are more properly called ‘indexes’. It makes sense, then, to start by looking at the different types of record we might come across.

This is the image of the original record (A) of my 5x great grandparents, James Calvert and ‘Sally or Sarah’ Brewer. The actual original is kept at West Yorkshire Archives, and although I haven’t seen that physical document, I can say I’ve seen ‘the original’ because I have this photograph of it. It tells us that James was from another parish: Bradford, whereas ‘Sally or Sarah’ was from ‘this’ parish: Calverley. They were married by Banns, and we can see that James signed the register, but ‘Sarah or Sally’ made her mark. These alternative names, together with the fact that on every other record I’ve found, the name ‘Sarah’ is used, suggests Sarah was her ‘proper’ name, but that everyone called her ‘Sally’. Then down at the bottom we see the names of the witnesses. We will never find a copy (transcription or index) of this document that includes all of this information. Even if what is transcribed is perfectly accurate it will not have all of these facts and visual clues.

Below is a document contemporary to the original. It’s the Bishops’ Transcript (B) of that same event. It was written up at the end of the year (1799-1800) and sent off to the bishop. This image is on FindMyPast. Unfortunately the entry for James and Sally/ Sarah is right down at the bottom of the page. I’ve lightened it but it’s still dark and not easy to read, but already we can see a difference between these two documents. This records simply the following: ‘James Calvert and Sarah Brewer by Banns’, plus the date: 8 Dec.

There are other records on FindMyPast and Ancestry for this event, e.g. FindMyPast has it in the England Marriages 1538-1973 set (C). It is a transcription only – no image – in fact this record set was created by FamilySearch, and used at FindMyPast with their permission. It records only the following information:

First name(s): James

Last name: Calvert

Marriage date: 08 Dec 1799

Marriage place: Calverley

Spouse’s first name(s): Sarah

Spouse’s last name: Brewer

There are other types of modern transcripts. If you’re lucky you might just come across a local genealogy website relevant to your interests with dedicated researchers who have transcribed lots of documents and made them freely available. The following is from such a site: CalverleyInfo. Here we can see a very full transcription (D) of James and Sarah’s marriage.

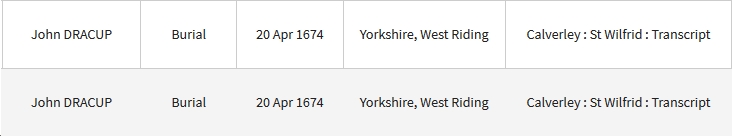

To illustrate more types of transcribed records I’m going to have to switch to a different part of my family, but still in the ancient parish of Calverley. These records are for the burial of my 8x great grandfather, John Dracup. I have the original record from the parish register (with image) and it reads: ’10 [April] John Dracup Junior of Idle Green buryed’.

Next, the entry for that burial on FreeReg (E). In fact there are two, and when I click on each one to view the transcript I see this is because the information has been transcribed by two different people, but the transcription is the same, and it does provide all the information on the original.

Source: FreeReg

My final example is from the Calverley page of GENUKI. There are a lot of transcripts for Births, Marriages, Burials and other related records on this page, including several different sets for the Calverley burials, transcribed and made freely available by a number of different people. One person, for example, has extracted all baptisms for people living in Idle for the years 1796-1800; other sets are for marriages arranged alphabetically by groom and by bride. The set I’m going to home in on is Calverley Burial Indexes 1596-1720, arranged alphabetically by surname (F), and transcribed by Steve Gaunt. Scrolling down to Dracup, this is what I find: a full listing of the burials of several generations of my ancestors, all in one place, and John Junior is right there in the middle. Again, all the information from that original has been included.

Apart from the original, right at the top, every other document you have just seen is a type of transcription. Some are indexes – they might serve simply to point to where information can be found. Since they are online most of them depend on the existence of a searchable index (G) so we can find them. What they have in common is that the information they record has simply been copied from somewhere else. That ‘somewhere else’ might be the original, or it might have been copied from another transcript. The Bishops’ Transcript has an unusual status in that it is a contemporary original document, but it is itself just a copy – a resumé, even – of the original entry in the parish register.

Beware!

So this is a good time to think back to my last post, and remember that every time the information is copied, there is the possibility of mistakes creeping in: human error, difficulties with archaic writing, inexperience, carelessness, administrative error…. Every single time something is copied there is scope for error. We must be mindful of that when we use them.

Where will we find these different types of record?

If you have a paid subscription to Ancestry, FindMyPast, The Genealogist, MyHeritage, etc then you’re more likely to have access to digital images of the originals. However, this depends on whether the archives where the originals are kept has licensed your subscription site to share them. For example, FindMyPast has a licence agreement with Staffordshire Archives Service which means they can provide Births, Marriages, Banns, Marriage Licences, Burials, Wills and Probate records – all with images of the originals. On Ancestry, at the time of writing, you’ll find ‘Staffordshire, England, Extracted Church of England Parish Records, 1538-1839’ – these are just transcripts, no images of the originals. On the other hand it is Ancestry that has the licence agreement with Wiltshire, and you will find all the parish records with images on that site. FindMyPast currently has simply the Indexes. Neither site has originals of parish registers from Berkshire. Transcripts (or ‘indexes’) are all that is available. When we progress beyond the basic census and civil Births, Marriages, Deaths, it makes sense to choose our subscription website based on availability of the older parish registers that you need.

The transcripts and indexes, on the other hand, tend to be freely available. As indicated above, you may find them on the GENUKI page for your parish, on FreeReg, through a local family history society, or a local website dedicated to making genealogical records available, like the CalverleyInfo site. You’ll also find them for free on FamilySearch (although FamilySearch do also have a lot of images of parish registers that you can browse) and you may even come across a brilliant site like one I sometimes refer to for my Wharfedale ancestors: Wharfegen Family History, which is a very trustworthy, ongoing project to construct the family lines and histories of every person who lived in the Wharfedale and Craven areas of Yorkshire.

That’s a LOT of possible transcripts!

So how can we make the best use of them?

* Firstly, a transcript is infinitely better than nothing

The original might have been lost, or it might not yet have been photographed for use on subscription websites. You might not be able to get to the archives where the original is stored, or it might have become too fragile for public perusal. You might not have the cash to access the subscription website where the records are kept, or any subscription website for that matter. For all these reasons, we can be very grateful for transcriptions and indexes. Although I don’t need that particular FamilySearch transcription (C) above, there are still some events for which the FamilySearch transcription is all I have. But if I use a transcript I always make a note of that, if possible I note where the originals are to be found, and if an original becomes available online I replace it as soon as I can.

* Second, even if you do have access to the original record, the transcript can help

Take a look at Original (A) above, for example. Can you read everything on there? I had trouble with the first name of one of the witnesses. Now look at Full Transcription (D), and there you have all the names. Someone has kindly done the work for you. All you have to do is decide if you agree.

* Third, you can use the Bishops’ Transcript to confirm a modern transcript of the original, or to help with illegible writing on the original

OK, so the Bishops’ Transcript (B) above is NOT a good example of this. But mostly they are very neat and the photographed image is NOT too dark to see. Anyway, trust me – you can.

* Fourth, the Bishops’ Transcript is also great if you have a subscription with a website that provides this but not the original parish register

I gave a few county examples of this above, but I have an ongoing example relating to my own research. West Yorkshire parish registers are on Ancestry but not on FindMyPast. However, FindMyPast has the Borthwick Institute records from York which include the BTs for the whole of Yorkshire. For this reason alone I need subscriptions to both sites.

* Fifth, if your subscription site doesn’t return an existing record, try searching on a different site

I gave this example in my last post: I couldn’t find a marriage for my 5x great grandparents. His name was Thomas Mann and she was Sarah. I felt sure her surname would be Creak, since that was the middle name given to their son, my 4x great grandfather. There was no such marriage showing up on Ancestry or FindMyPast. Eventually, it was FreeReg that came to the rescue (example E above is from this site). The problem here was in copying the name to the index. Ancestry did have the record, but their index gave the bride’s surname as Cooke. There’s no guarantee that FreeReg will be right and Ancestry will have it wrong of course. It could be the other way round. But it’s an example of the benefit of having a variety of sites and indexes (G) at your fingertips, and swapping between them all when you can’t find something. Remember – there is scope for human error in every index, and if the index is not correct we will not find our records on that site.

* Sixth, if you come across a transcription that’s arranged alphabetically instead of chronologically, use it as a checklist

That was how I used the alphabetical transcription (F). I found I had almost all of these burials but a couple were new to me. All I had to do was search for these specific records on my subscription site, and the records appeared.

* Finally, if you come across the work of a dedicated and trusted researcher thank your lucky stars – but still search for the evidence!

With practice, you can tell which researchers you can trust. Their work is careful and meticulous, thoroughly sourced, well organised… I’ve named three such examples above: the CalverlyInfo site, the Calverley page on GENUKI (although not all pages on GENUKI are as well padded) and the Wharfegen site. If you come across a site like any of these you can do a happy dance. Even so, use it as a starting point. Look for the originals. And if you can’t find the originals cite them and their website as your transcription source.

I hope there are some new ideas for you amongst that little lot. Have you any other interesting ideas for making the most of transcriptions? If so, why not leave a comment.