Getting your head around ‘Half’ relationships can be tricky. In regular life we probably wouldn’t make a distinction between a half cousin and a full cousin. Yet when we’re working with DNA, and indeed if we’re looking for a missing parent or grandparent, ‘Half’ relationships are important. The Shared centiMorgan Project chart shows that we are likely to share different amounts of DNA with full and half cousins. On average, we share 866 centiMorgans (cM) with a full cousin – although because of the random nature of DNA inheritance it could be as low as 396 and as high as 1397cM. By contrast, we share, on average, 449cM with a half cousin, although it could be as little as 156 and as much as 979cM. Similarly, with a second cousin twice removed the average is 71cM, but it could be as little as zero and as much as 244cM. For a half second cousin twice removed the average is 48, but the range is from zero to 144cM.

(If you’re having trouble working out what relationship a person is to you, I shared a Cousin Calculator a few years back which should help with that… but doesn’t include Half relationships.)

Half relationships, then, are important in genetic genealogy. The amount of DNA we share with someone is a clue as to how far back we connect, that is, where we should be looking for our Most Recent Common Ancestor. In fact, if you go back to the Shared centiMorgan chart, there’s a little box at the top where you can type in the amount of DNA you share with someone and it will provide you with a range of possibilities, and the likelihood of each.

What is it that makes someone a half cousin, a half aunt, or a half sibling?

It’s all about our direct line ancestry

We all have:

2 biological parents

4 biological grandparents

8 biological great grandparents

16 biological great great grandparents

and so on.

If, instead, we think of them as ‘pairs’, we all have:

1 pair of biological parents

2 pairs of biological grandparents

4 pairs of biological great grandparents

8 pairs of biological great great grandparents

and so on.

It doesn’t matter if these people were married, having a clandestine relationship or any variation on that. The fact is that any individual (let’s say person ‘A’) is born of two specific people. If one of these people – these biological parents – has another child (we’ll call that child person ‘B’) with a different partner, then biologically A and B are Half siblings, and anyone descended from each of them will also have the Half DNA relationship in relation to the other ‘branch’ of descendants..

The point to emphasise here is that whether someone is your Half sibling, your Half aunt, your Half cousin or your Half 3rd cousin twice removed depends on what happened in your direct line at the point where you and your DNA match’s lines intersect. If your Most Recent Common Ancestors are a pair, your relationship will be a full sibling/ aunt/ cousin or 3rd cousin twice removed, etc. If your Most Recent Common Ancestor is just one person, your relationship will be ‘Half’.

Cousins and Half Cousins

All of the above may be obvious, but it’s an essential foundation for what I think may be the bit most people have trouble with: first cousins.

If my uncle has children, my cousins, and then remarries and has more children, those younger children are half siblings to his older offspring. So are they my half cousins?

No, they are not. The reason for this is that for a Half relationship to exist between you and another person, there must have been a change of partner in YOUR direct line. The remarriage of an aunt, uncle, great aunt, great uncle, and so on, has no impact on YOUR direct line.

In the above scenario, the reason my uncle’s two sets of children are half siblings is because there is a difference in the biological partnering in their own direct line, that is: at the level of their own parents. However, the reason my cousins are my cousins is because their father is my parent’s brother. Our Most Recent Common Ancestor is our grandparent couple. The mother of my uncle’s children is linked to me only through that marriage/ relationship, and not through biology. Therefore his children may be half siblings to each other, but they are all full cousins to me.

How about if my uncle died and his wife – my ‘aunt’ only by marriage to him – remarried and had more children with her second husband. We may all get on like a house on fire. My aunt by marriage may be as much a part of our family as I am; and we may welcome her new husband and consider their children, alongside the children my ‘aunt’ had with my uncle, as our cousins. But in the true biological/ DNA sense, whereas her older children are my full first cousins, the second tier of her family has no connection to me whatsoever.

Whichever way you look at it, all of my uncle’s children are my full first cousins, regardless of how many partners he has had, because we are all descended from one Most Recent Common Ancestor couple: our grandparents.

Searching for an unknown father

Let’s suppose I’m searching for an unknown biological father. If he has other children, they and their descendants would share only one Most Recent Common Ancestor with me: that would be our father. We would have different mothers and would therefore be Half siblings. Children of the half siblings would be my half nieces and nephews, and they would be Half cousins to my children. Their descendants would always retain the ‘Half’ biological relationship.

But something changes when you start to work back from the biological father. Beyond him, right back into the past, all relationships are ‘Full’, not ‘Half’.

The biological father’s sister would be my full aunt, because our Most Recent Common Ancestor is a couple – her parents/ my biological grandparents; and her children would be my full cousins.

This applies at whatever position in your family tree you have an unknown ancestor: father, grandfather, a grandmother who ‘disappeared’ and turns out to have had a second family, and so on. Everyone descending from that SINGLE Most Recent Common Ancestor is a ‘Half’ relationship; all ancestors further back beyond that person is ‘Full’ – a full aunt, cousin, great uncle, and so on.

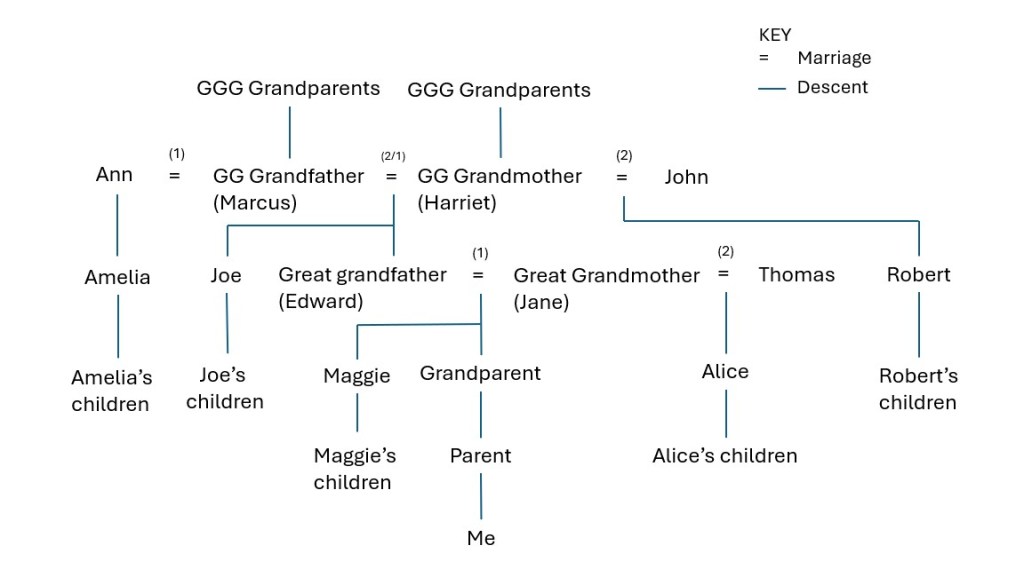

To conclude, here’s a family tree chart from one line of my own family tree. Right at the bottom in the centre you see me, my parent and my grandparent.

My great grandmother, Jane, was married to Edward and they had several children, including my grandparent and Maggie. When Edward died Jane married Thomas and they had one child, Alice.

Alice is half sibling to my grandparent and great aunt Maggie, although within the family she was simply their sister.

Maggie’s children are my parent’s full cousins. Biologically, because the Most Recent Common Ancestor is just one person – their grandmother Jane – Alice’s children are half cousins to Maggie’s children and my parent. Within the family no such distinction was ever made, but in DNA terms there is a distinction.

My great grandfather Edward’s mother, Harriet, also married twice. She was married to Marcus, and had several children, including Edward and Joe. Before marrying Harriet, Marcus had been married to Ann and they had a daughter, Amelia, who was brought up by Harriet after Ann died very young. After eight years of marriage to Harriet, Marcus also died. Harriet then married John and had more children, including Robert.

Joe and Edward are full siblings. Amelia is their half sister, because they share the one Most Recent Common Ancestor: their father, Marcus.

Robert is also half sibling to Joe and Edward, because they share the one Most Recent Common Ancestor: their mother, Harriet.

Amelia and Robert may well have considered each other as siblings, but biologically there is no connection whatsoever between them.

The children of Edward and Joe (including Maggie and my grandparent) are full cousins. Amelia’s children are their half cousins.

Alice, and Robert’s children, have no DNA connection to Amelia’s children, nor do they have a DNA connection to each other, although they may have thought of each other as cousins.

However, further back than Marcus and Harriet, all ‘Half’ relationships cease. If Marcus is the Most Recent Common Ancestor of Amelia, Joe and Edward, then Marcus’s parents are also common ancestors. Therefore any brothers or sisters of Marcus will be full uncles or aunts to all of Marcus’s children. Similarly, if Harriet is the Most Recent Common Ancestor of Joe, Edward and Robert, then her parents will also be their common ancestors, and as such any full brother or sisters of Harriet will be full uncles and aunts to all of Harriet’s children, regardless of who the father is.

The reason for including that chart and explanation was to illustrate some of the points raised above. It turns out also to illustrate how complicated this can be! So if you’ve been scratching your head trying to understand full and half relationships, and why the ‘Half’ has come about, I hope the first half of this post will help. If, after that, you can interpret the chart and work out who is ‘Half’, who is ‘Full’, who has no biological connection, how this impacts on previous generations, and how this affects DNA, then you have nothing to worry about. 😀

![Extract from burial register, 1663. The extract is in seventeenth century handwriting and reads 'South Ile Will[ia]m Clareburne de Westgate buried eodem die'](https://englishancestors.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/william-clareburne-burial-1663.jpg?w=1024)