With a nod to St Patrick’s Day, here’s a little something for those of you with ancestral lines going back to Ireland (and maybe Scotland too).

One of the difficulties for family researchers with Irish lines is that prior to around 1840 Irish life events are not well-documented. Of my six direct ancestors who were born in Ireland, English records tell me that one was from County Mayo, one from Belfast and two were, at least at the time of their daughter’s birth, in either Derry or Newry. For the other two I have only ‘Ireland’. I have fathers’ names (from English marriage certificates) for only two.

So for any of you with Irish ancestry from before about 1850, you’ll know that we have to think laterally and draw upon any clue we possibly can. One such clue could be the traditional naming pattern, which was widely used in Ireland across all sections of the community until the late 19th century.

It goes like this:

1st son named after paternal grandfather (patGF)

2nd son named after maternal grandfather (matGF)

3rd son named after father (F)

4th son named after father’s eldest brother (patB)

5th son named after mother’s eldest brother (matB)

For girls the same system applied, but it was not always followed as rigorously:

1st daughter named after maternal grandmother (matGM)

2nd daughter named after paternal grandmother (patGM)

3rd daughter named after mother (M)

4th daughter named after mother’s eldest sister (matS)

5th daughter named after father’s eldest sister (patS)

For both girls and boys, sometimes the order in which grandparents were honoured could be switched, i.e. maternal first or paternal first.

I learned about this tradition only a year or so ago. Recently I’ve read (in online comments) that it applies to Scottish ancestors too. I don’t have Scottish ancestry so can’t put it to the test, but if you do you could try it out for yourself.

I decided to try it with my Mayo family. This is all I know for sure:

- I believe Margaret and John came to England separately.

- They married in England in 1857. John’s father was Patrick; Margaret’s father was James.

- The 1911 census indicates Margaret was from Mayo.

- John died before the 1911 census. Earlier censuses give only Ireland as his place of birth. However, DNA matches indicate that he too was from Mayo. Using them I have narrowed his birthplace to a specific area of the county, but I don’t have a baptism, and therefore no mother’s name.

- Using this information, I have found a baptism record for Margaret in Aghagower. This is supported by a DNA match in the same township, probably at the generation before. If it is correct then I have the mother’s name: Honour.

- This is the only Margaret born to a James with that surname in the whole of Mayo and within a likely time period (Margaret was not sure of her age) showing in all records. However, another group of researchers have claimed this family for their own, and one of us is wrong. We always have to bear in mind in situations like this that the records we see are not necessarily a complete set.

I’ve looked at Margaret and John’s children’s names, and also the names given by two of their children to the following generation. All children of both generations were born in England but within a strong Irish migrant community. I’ve included the date of marriage of each couple, since it’s said that by the end of the 19th century this tradition was dying out in favour of fashionable names. It’s also said that the tradition was never applied as strongly in relation to the naming of daughters as for the naming of sons.

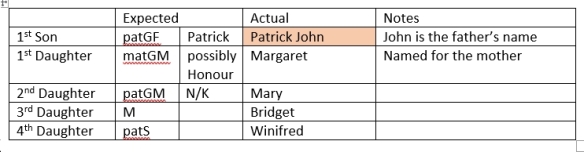

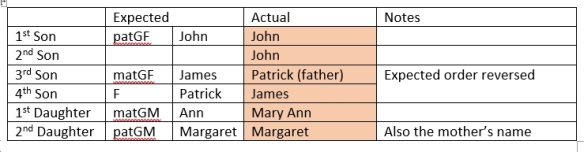

The detail of the tables that follow will be of no interest at all to any of you. Instead, just focus on the highlighted boxes. Where a child is named as expected I have coloured the square peach. If the expected naming order of two consecutive births is reversed but the expected names were still used, I have also highlighted this peach.

John and Margaret (Irish, now living in England). Married 1857

Patrick and Margaret (Both of Irish descent). Married 1880

With only two slight deviations Patrick and Margaret did it by the book: their first son died before a second was born. They therefore re-used the paternal grandfather’s name for their second son. They also reversed the expected order of father and maternal grandfather.

With only two slight deviations Patrick and Margaret did it by the book: their first son died before a second was born. They therefore re-used the paternal grandfather’s name for their second son. They also reversed the expected order of father and maternal grandfather.

Bridget and George (Bridget of Irish descent). Married 1885

Bridget and George named their three sons in exactly the expected order. Regarding their daughters, the first two were named after grandmothers. The third, instead of being named for the mother, was named to honour the father’s grandmother who had recently died. The fourth daughter was then named for the mother, so this was only a slight deviation. The final two daughters were named Martha and Winifred. Following the traditional system, Bridget’s eldest sister was Mary. This name however had already been used (paternal grandmother) and so Winifred was named after Bridget’s only remaining sister.

This leaves only the name Martha which cannot be accounted for. However, since Bridget has stuck so closely to the traditional pattern, it’s reasonable to assume that Martha is an important name somewhere in the Irish lines. In other words it’s something to look out for if I were ever to find records of possible families for John and Margaret back in ireland.

How might we be able to use this information?

I can think of three ways.

First, it’s nice to know who our grandparents and other relatives were named after. Of Bridget and George’s children, for example, I knew Annabella and John. Knowing that John was named after his grandfather, and realising that Annabella (who was known as Bella in the family) was named after her own great grandmother somehow brings me closer to those people whose lives I’m researching but who died long before my birth.

Second, it gives us a little more information about our ancestors’ lives and what was important to them. This was clearly an important tradition, and perhaps all the more important for second generation migrants because it connected them back to their lost homeland.

The third way of using this information involves a bit of lateral thinking…

Moving back to my GG grandparents Margaret and John, because of gaps in my own knowledge/ the records, I’ve only been able to accept one of their children’s names as following the expected pattern: Patrick John was named after his paternal grandfather and his father. What we can plainly see, however, is that they passed on an understanding of the naming traditions to their own children. Surely, then, they would have used it themselves? (Alternatively, might Patrick and Bridget have followed it more closely than their own parents did because they wanted to honour the traditions of their ancestral land?)

It’s the daughters’ names that can’t be verified. As explained above, I have Honour as a possible mother for Margaret, and yet Honour doesn’t feature at all amongst the four daughters. Perhaps the baptism record I have is incorrect? Or might Honour have been known in the family by her confirmation name to distinguish her from another Honour? What all of the above does suggest is that it’s worth my while looking for the following names in any possible records that might come to light:

Girls: Margaret, Mary, Bridget, Winifred, Mary

Boys: Patrick, John, James

Using DNA matching I now know that while John and Margaret came to England at the time of the Great Hunger (the famine), most of their cousins emigrated to Pennsylvania. Bearing that in mind, and armed with the naming tradition information and the above names that are important for my Mayo family, one online family tree really interests me:

John and Maria Padden, contemporaries of my own GG grandfather John Padden, Married in Crossmolina, Mayo, in 1860 before emigrating to Pennsylvania. This is how they named their children.

Could this John be my GG grandfather’s cousin, or perhaps second cousin?

John and Maria definitely followed the naming pattern tradition. Most of the important names – grandparents and mother – are accounted for. Only the father’s name is not passed on. Instead, the first son is named Patrick. After the three important women’s names are passed on, three others that cannot be accounted for are used: Margaret, Martha and Winifred. The overlap with names given to my own family is striking. This is almost the same family living in parallel across The Pond!

Clearly, none of this gives any conclusive proof. The idea is merely, in the absence of records, to look for pointers suggesting family connections – leads that might add a little further weight should a possible baptism record eventually come to light. And DNA matching shows that this family is definitely related to me.

I hope some of this has been useful to you. If you have Irish or Scottish ancestry and hadn’t heard of the naming tradition, why not give it a go and see if there are any conclusions to be drawn from what you find?

*****

Finally, I hope that all of you and your families are keeping well, and coping with self-isolation and all that involves.