Today’s post is an interloper amongst my little ‘Ancestral Tourism’ series. It follows on from Part 1: Churches and Churchyards, Part 2: Municipal & other Public Cemeteries and Part 3: Graves and Gravestones. I’ve stepped away from the ‘Ancestral Tourism’ series here because this is something you can do online, whether you visit the grave or not – although it is, of course, also great preparation for a trip to the actual cemeteries.

The aim here is to show how the information from various records relating to burials, and even the same records on different platforms – including the gravestone itself if there is one – can be combined to give a greater depth of knowledge and understanding about an ancestor and their family. This technique of layering up information from different records works equally well with other aspects of an ancestor’s life, of course, but here I’m focusing on burial.

I hope this will be of interest to readers researching at Intermediate level, or moving on from Beginner to Intermediate level.

First, a comparison of records from two different cemeteries

Precisely what is included on the record varies from one cemetery to another, and possibly from time to time. I can illustrate this by comparing burial records for two of my ancestors: a 4xG grandmother and a 2xG grandmother. Both died after the introduction of Civil Birth, Marriages and Deaths, and I had already located the death entries on the General Register Office (GRO) online register, and bought one of the Death Certificates.

What the records include

This first record is from York’s Fulford Cemetery. It includes so much information that there is no need to buy a Death Certificate. CLICK FOR BIG!

Here, we see that Sarah Wade, bottom entry, was buried in the York Public Cemetery at Fulford Road in 1860. She has the burial reference ID of 11,365 and is interred in Grave number 3837. She died on 9th March 1860 and was buried on 14th March. Sarah was 75 when she died and was the wife of John Wade, gentleman. They lived in Stonegate, York, but the number of the property is not given. Cause of death was pneumonia. The informant was Edwin Wade of 4 Coney Street, York. The final column is the name of the officiating minister.

There is more to this information than meets the eye. Sarah is the wife of John Wade. This means he is still living. You can see that the entry above Sarah’s describes the deceased, Emily Johnstone, as ‘Relict of the late Spearman Johnstone, Gentleman’. A less formal term would simply be ‘Widow’.

The second and third entries in this extract are both men. One is a Captain in the Militia; the other a Fishmonger. Men, then, are described by their Trade, Occupation or Profession. Women are described by their marital status, or ‘condition as to marriage’. The top entry is a child. Children are described as ‘Son/Daughter of’ followed by the father’s name.

The informant is not John the husband, but another man with the surname Wade, therefore probably related. He is in fact the oldest son of Sarah and John, and he is clearly used to signing documents with a flourish!

*****

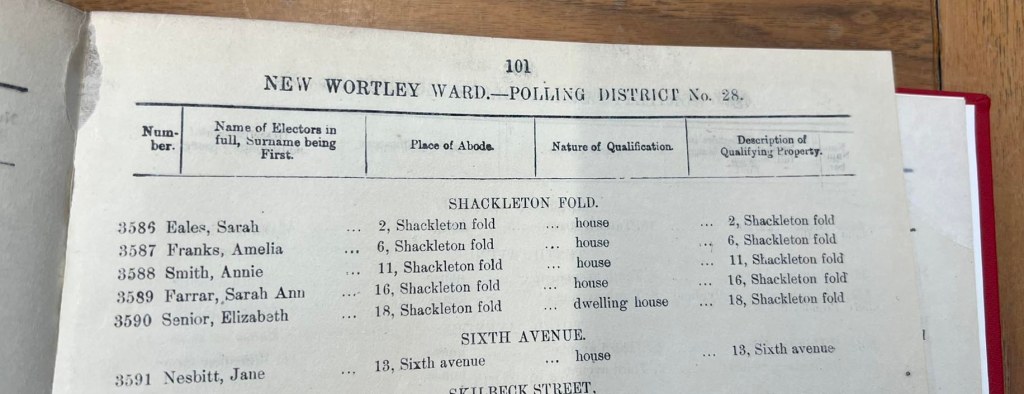

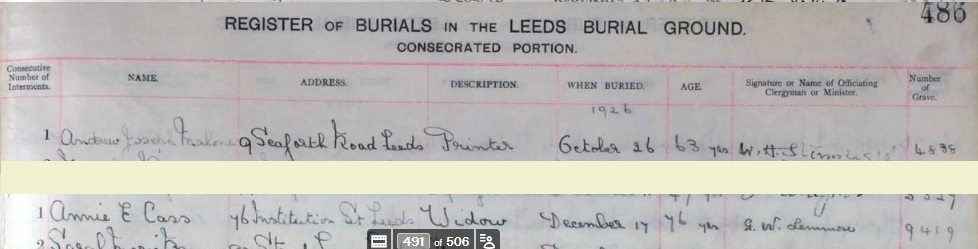

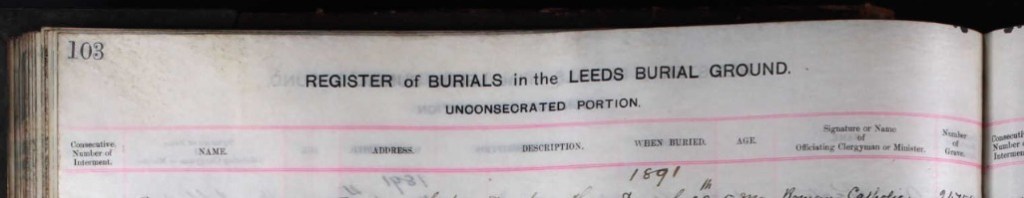

The next record is from Beckett Street Cemetery in Leeds. The cream line just indicates where I have removed several lines from the page because it’s only Annie E Cass that we’re considering here.

Source: ancestry.co.uk Leeds, England, Beckett Street Cemetery, 1845-1987

In this record we see that Annie E Cass, bottom entry, was buried at The ‘Leeds Burial Ground’. This is the same as ‘Beckett Street Cemetery’. She was buried in the consecrated portion on 17th December 1926. Address at time of death was 76 Institution Street, Leeds. Annie was 76 years old and a Widow – again, we see that the top entry, a man, is described by his profession. Annie in fact ran a business after her husband’s death 28 years earlier, but this is not mentioned. The penultimate column is for the signature or name of officiating clergyman or minister, and finally we have the Grave plot number, which is 9419.

There is not as much information as on the Fulford Cemetery entry above. We don’t have an informant or date of death, and the late husband’s name is not included. We also don’t have a cause of death. To cover all bases on this one we might want to purchase the Death Certificate. What we do know, however, is that Annie was buried in the Consecrated Portion of the cemetery. She was therefore Church of England. (I already knew that as I have her baptism record, but sometimes every little helps!)

*****

Gathering information from several documents and platforms

Now I’m going to home in on Annie, or Annie Elizabeth Cass to use her full married name. I want to see if I can add to my knowledge and understanding of her life and family by looking closely at all the records I can find relating to her burial.

The information from FindAGrave (below) is a transcript compiled directly from Annie’s burial entry above. You can see that all the information is accurate, but the marital status is not included, and it is not clear whether Annie died on 17th December or was buried on that date. This is why seeing the original is always preferable, but if that’s not possible, a transcript is infinitely better than nothing. In fact I do already know that Annie died on 14th December, because I did previously buy a copy of her Death Certificate. I also know that she was in hospital when she died, not at her home in Institution Street; and I know which of her children was the informant, and his address at the time – which in turn tells me he was still living in December 1926.

So why did I bother looking at FindAGrave?

In this case I had two reasons for doing so:

- I wanted to see if there was a photograph of the gravestone;

- I was creating a list of all my ancestors and their children buried at Beckett Street Cemetery, and since I already had information from the GRO online register about the deaths of each, the search process on FindAGrave is much quicker and easier than searching on Ancestry. The resulting list is below:

By compiling a list of all my ancestors and their children at this cemetery I was able to see which ones were buried in the same plots as other family members. Here, I identified six members of the Cass family, all in Plot 9419. I made similar lists for all my family members at various public and municipal cemeteries. This will make it easier to navigate the cemeteries when I visit.

The fact that Annie Elizabeth and her husband John William Cass were able to purchase a family plot tells me something about the financial situation of this family. Many of my ancestors at this time couldn’t do so. I already knew they had a family business so this was not a surprise. I expected, too, that there would be an inscribed headstone. However, although many of the entries at FindAGrave are accompanied by a photograph of the grave, this one isn’t. My plan was to take a photograph when I visited myself.

Additional information on Friends of Becket Street Cemetery website

This was the point I had reached when I wrote my last post, about Municipal and Public Cemeteries; and that was when I found the fantastic Friends of Beckett Street Cemetery website.

Using the public search facilities on the Friends website, and bearing in mind I already had a lot of information about this family, including the plot number where they are buried, I was able to do the following:

- View the cemetery register. I already had access to this register via my subscription to Ancestry.co.uk. so there was nothing new for me personally here.

- Locate the grave on a map of the cemetery.

- Locate the grave on a spreadsheet. Here, it is recorded that in fact there is no headstone for the family plot. This surprised me.

- The spreadsheet also provided a tantalising promise of some extra information. I found there were seven people buried in this plot, rather than the six I already knew about. However, to see the list of people (and more) I needed to become a Friend of the cemetery. This costs £10 per year. Bearing in mind the number of ancestors I have in this cemetery, and the good work the Friends do, this was worth it.

- Having paid the membership fee I could now view the names of all occupants of this plot, and use various methods of searching the dedicated Beckett Street Cemetery database, which yielded better results than searching on the huge Ancestry database.

- There is also a virtual walk along the various paths so that you can locate and see the plot you’re interested in.

**Obviously, every ‘Friends Of’ group will provide different search facilities.**

Here’s the new information I got about this family, and how I was able to use it

The first thing to note is that the ‘Person ID’ on the FindAGrave website is a ‘FindAGrave’ ID. The cemetery Person ID/Reference is different, so I have amended my lists to include both.

Next, I was anticipating the the unknown additional person could be a missing child. My research showed that Annie Elizabeth lost four of her children in infancy, but on the 1911 Census she wrote that she had lost seven children and had six still living. I knew this to be inaccurate, because seven of the children were still living in 1911. However, this still suggests two missing babies. Might one of them be buried in the family plot?

Alternatively, could the extra person be Annie Elizabeth’s oldest daughter. Aged 40, she was still living with her mother in 1911 but was nowhere to be found in 1921. Had she died? It seemed inconceivable that she wouldn’t have been buried in the family plot.

The extra person turned out to be Annie Elizabeth’s mother-in-law, Elizabeth Cass. Elizabeth died in 1878. She is the mother of Annie Elizabeth’s second husband, John William Cass, and they are not my ancestors. Although I had her name and some brief details from a census record I had not researched her. This record provided her burial dates and also her address, which was the same shop and living quarters above the shop that I knew to be the home of Annie Elizabeth and husband John William Cass in the 1870s.

This prompted me to look for a burial record for Elizabeth’s husband, William Cass, located quickly on the Friends of Beckett Street Cemetery website. He too had died at the same address, five years earlier. Using death certificates and baptism records for several of Annie Elizabeth’s children, I was able to calculate that she had moved into the shop with her husband and children after the death of Elizabeth’s husband/ John William’s father. The possibility that they had taken over an existing family business was not something I had previously considered.

As for the missing deceased children – the little ones are still missing. I suspect Annie Elizabeth may have included stillborn children in her totals. I have long suspected that women did this on the 1911 Census as a way of commemorating their children who never had a proper burial.

However, this new information also prompted me to renew my efforts to find Annie Elizabeth’s oldest daughter. I found she had married shortly after the 1911 census and in 1921 was living with her husband and a daughter, whose life I will now have to follow through.

How strange that all this should be resolved as a result of examining cemetery records! Plus I am now a member of the Friends of Beckett Street Cemetery!

It all goes to show we should examine closely, keep an open mind, follow all leads and cross-reference. I hope you’ve found this useful, and that it might prompt you to look again at some of your mysteries.

![Extract from burial register, 1663. The extract is in seventeenth century handwriting and reads 'South Ile Will[ia]m Clareburne de Westgate buried eodem die'](https://englishancestors.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/william-clareburne-burial-1663.jpg?w=1024)