In Leeds last month, I spent two days in the Local History department of the wonderful Leeds Central Library. I had a big task to complete, started last year, that will help me progress my Shackleton’s Fold One-Place-Study.

Comprising only nineteen properties, Shackleton’s Fold existed for less than a hundred years. It was built around the mid-1840s, precise year not yet known; and from 1895 until demolition circa 1938, was populated by quite a lot of my family members.

There are various strands to this One-Place-Study. First, the properties themselves – poor quality Back-to-Backs, or rather ‘Blind Backs’, since Shackleton’s Fold comprised just two rows of houses, each with the door and windows only on the front. The back of the house, instead of joining onto another identical property with the windows and doors on the other side, was simply a solid wall. No windows, no doors, and no other house. My study will include contextual information about Back-to-Backs, the industrial era working class housing for which Leeds is famous. Next, there are of course the people who lived there: the family members who lived in each of the houses during the time they stood. I’m interested in their stories, as well as what their lives reveal more generally about the lot of the labouring classes in this part of Leeds, during the second half of the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries.

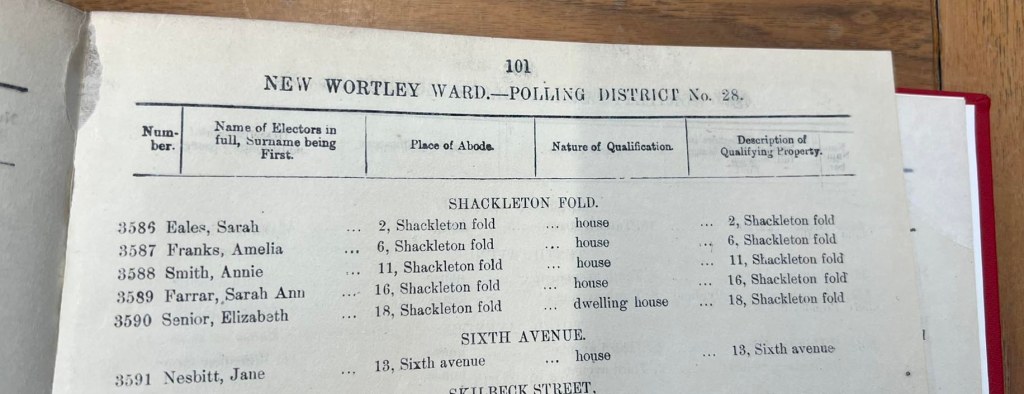

Before I can delve into their stories I need to find out who they are, and that’s what I was doing in the library: compiling a list of everyone on the Electoral Registers and Ward Lists. The objective was to use these to fill the gaps between the decennial censuses. This would enable a fine-tuning of the periods of residence for each household. If a named head of household was present for the 1861 and 1871 censuses but not the 1881, the registers could allow me to pinpoint the exact year they moved out.

Cataloguing the voters of just nineteen houses for around ninety-five years didn’t seem like such a big task, particularly since at the beginning of the period none of the residents had the vote. However, it has taken three full library days for me to do it – and even now I’ll need to return to check a few omissions and discrepancies.

Throughout the nineteenth century the population of the Borough of Leeds grew rapidly. In 1861 it was 311,197, rising to 503,493 in 1891 and by 1931 – the last Census for which Shackleton’s Fold was inhabited – the population stood at 646,119. This meant that the arrangement of the registers had to change. The sheer numbers of voters in these various registers meant they had to be divided into manageable chunks. Navigating these was a huge task. For example, a volume might bear the title ‘Borough of Leeds Ward Lists 1881 Part 2’, but with no indication as to which parts of Leeds were in Part 1, Part 2, etc; and this meant each ‘Part’ had to be browsed until the area needed was located. There was no guarantee that the following year would be similarly arranged, so the whole process had to be repeated.

If you’ve worked with Electoral Registers you’ll know that they are further divided into specific polling districts. The only way to work out which one you need is to look at the most likely ones until you find streets with names you recognise as local to your place of interest. Once you’ve done that you might think you’ve cracked it, and you’ll be able to whizz through the rest in no time. However, these polling districts also change. For example, in 1870, Shackleton’s Fold was in Polling District No. 31. In 1894 it was in West Division Polling District No. 28; changed to District No. 32 by 1899; then District 33, later to 39 and so on.

It gets worse! Electoral Registers list only those people entitled to vote in Parliamentary elections; and part of the appeal of a One-Place-Study for Shackleton’s Fold is that it existed throughout a period of great social change, including the move towards universal adult suffrage. During this time, some people were entitled to vote in Municipal but not Parliamentary Elections, and it’s interesting to chart the changes and know that behind each gain there was an important piece of legislation granting the vote to another group of people. This will definitely be covered in my One-Place-Study. However, since those entitled to vote only in Municipal elections could not be included in the Electoral Registers, there had to be another series of registers to list them. Therefore, alongside the Electoral Registers, there are also Ward Rolls, sometimes called Burgage Lists. Here, alongside the men included on the Electoral Registers, we find women and other men whose situation entitled them only to this local level of voting. Consequently there are (at least) two volumes of voters for every year. And guess what… the Polling Districts in the Ward Rolls have different names to those in the Electoral Registers! Shackleton’s Fold starts out in 1860 in ‘Holbeck Ward, Township of Wortley’. By 1874 it is the ‘Holbeck Ward Township of Wortley No. 3 Division’, and a couple of years later it’s No. 1 Division. By 1881 we have ‘Polling District No. 23 New Wortley Ward, Township of Wortley’, then ‘New Wortley Ward Polling District No 28’, and so on. By the 1920s even the township changes, to ‘Armley & Bramley’ and briefly to ‘Polling District MM Township of Leeds’.

As if that wasn’t difficult enough, it wasn’t until 1880 that voters were arranged by address. From this point forward, voters in Shackleton’s Fold are listed together, from number 1 to number 19. Before that year, locating each person involved line by line examination of every entry in the appropriate Polling District – once that had been found – and looking for the magic words ‘Shackleton’s Fold’, then making a note of the name of the person shown. Numbers of individual properties are not given, and since people often tended to move from house to house as their needs changed, there is no way of knowing for sure where each person resided other than at the decennial Census check-ins. Certainly from 1880 onwards the process was quicker, allowing for the speedy capturing of names and addresses with photographs of the relevant pages… at least, provided the Polling District hadn’t been renamed.

That said, for quite a few of the years, even after 1880, the women are listed in a separate part of the book, at the end of the entries for that polling district. Special mention must be made of the ‘Borough of Leeds Ward Lists 1872 Part 4’ in which, possibly because of a misunderstanding on the part of whoever compiled it into the one bound volume, locating the information involved examining every line on all 190 pages.

If you’ve ever worked with Electoral Registers, I’m sure some of the above will be familiar; but I suspect not so many of you will have been tracing the families of an entire street throughout a ninety-five year period! My advice to anyone planning on using Electoral Registers and Ward Rolls is: to allow far more time than you expect you’ll need; to understand the difference between the two, and their layout; and to make notes of the different Polling District names for each as you progress. This was a lesson hard learned for me, and explains why I now have a list of queries, and even a few volumes I now realise I missed.

That said, doing this is an essential foundation for everything that will follow. In addition to the decennial censuses from 1851 to 1921, the Electoral Registers and the Ward Rolls, I have information from The Borough of Leeds Poll Book. This was the first general election to be held after the passage of the Reform Act 1867, which enfranchised many male householders. Poll Books differed from Electoral Registers in that whereas the latter list who is entitled to vote, the former list not only who did actually vote, but also for whom they voted. It would not be until 1872 that the Secret Ballot was introduced, and so for many of our ancestors this is a once-only insight into their political affiliations. Other useful name-rich listings may include Directories and even addresses included on baptism and marriage registers. Luckily for me, for much of this period, all Church of England registers for Leeds are available on Ancestry.co.uk. – but not Roman Catholic or most Nonconformist registers.

These lists of people will form the basis of a database of every household, arranged alphabetically by surname. What I had really intended was simply to use these voter lists for fine-tuning periods of residence. I had anticipated that the real sources of information about the families would be the censuses. However, some residents lived in Shackleton’s Fold for only a very short period of time; and since all I have is the name of the head of household, there is no way of finding out more about them. The identity of a Thomas Brown, for example, who is listed on the Electoral Roll of 1871 and nowhere else – not even on the Census of that same year – will forever be unknown. However, Isaac Lord, also resident just briefly in 1870, turns out to have a sufficiently uncommon name for me to be able to track him down. Similarly, the juxtaposition of the head of household with his wife’s name on the Ward Lists may be sufficient to track a couple down via a marriage record.

My brain hadn’t flagged up that the lists themselves would also, with very little additional research required, witness the expansion of suffrage. It will be interesting to compare each increase of names with the relevant legislation. The lists even chart the final years of Shackleton’s Fold, helping me to narrow down the likely year of demolition. In 1938 only one resident remained, and by the following year he, too, was gone. Soon, Shackleton’s Fold would be no more.

If you want to follow progress on this One-Place-Study, you’ll find all blog posts and other information [here].