This is part four in my ‘Ancestral Tourism’ series. It follows on from Part 1: Churches and Churchyards, Part 2: Municipal & other Public Cemeteries and Part 3: Graves and Gravestones. The focus in this little series is on planning ahead so that you can spend the time when you’re there exploring, wandering, taking photographs and soaking up the vibes of the place.

In this post we’re looking at preparing for visiting former ancestral homes and business premises that are still standing. Trying to locate buildings no longer in existence will be covered in a future post.

Before you go

How do we know where our ancestors lived?

A range of documents may include the specific address or property name, or other clues as to the location of a former home or business of our ancestors. Examples are:

- Church records, such as Baptism, Marriage, Burial and maybe wider parish records

- Civil Registration: Birth, Marriage and Death Certificates

- Census records

- Correspondence between the person and an official body, sometimes found in archives, e.g. National Archives

- Directories

- Electoral Rolls

- Family business records

- Family documents, including letters and perhaps a family bible or other religious text

- Immigration and Naturalisation documents

- Military Records, including attestations and next of kin

- Newspaper reports

- Poll Books

- Probate Records, Wills, etc

- Property and Land records, including deeds, local tax, etc

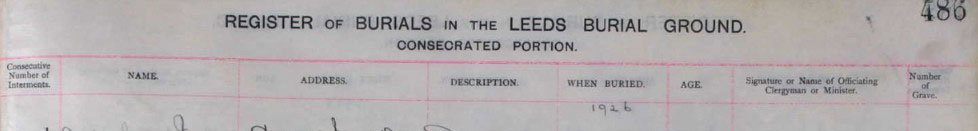

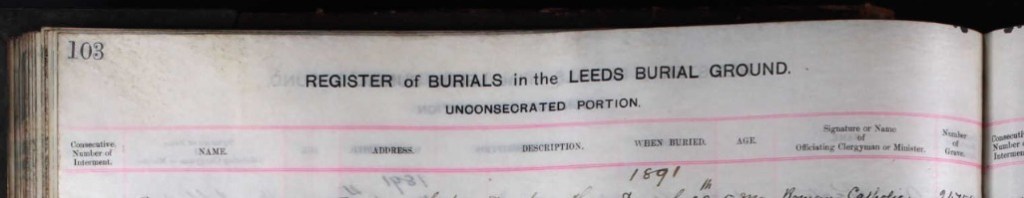

- Public and Municipal Cemetery registers

- School records

It’s certainly easier to track our more recent ancestors.

For earlier generations, even where we find an abode in the examples above, often an exact ‘address’ was not used. A street name without house number, or for smaller places even just the name of the village or hamlet may be the closest we’ll get. During the second half of the 19th century we find more documents that include information to guide us to a specific property. Earlier this year I visited Kinver in Staffordshire, where my 2x great grandfather and some of his siblings were born. The image below shows the extent of Kinver now, as viewed from the churchyard high on a hill above the village. The main High Street, dating from medieval times, is clearly seen in the image. Most of the properties beyond that are more recent. ‘Somewhere in this photo’ is the closest I will ever get to knowing where my ancestors lived here – but I’m happy with that.

Beware! House names and even house numbers can change

Even when documents do bear a house number or name, these may have changed – particularly if there was much additional building in the twentieth century. I researched the history of a house built around 1837 in what is now a built-up area of the Isle of Wight. The house number is 21, and my clients had already done some research into the nineteenth century inhabitants of ‘number 21’. However, using maps and other documentation I found that the house became number 21 only in the early twentieth century. For the first eighty or so years it was number 3. The change had become necessary to accommodate new building over the previous decades.

Similarly, a few years ago, I visited York to see my family’s properties there. Census records had my 4xG grandparents at 58 Stonegate. I found the property and photographed it, but afterwards realised Stonegate had been renumbered. Eventually I worked out that their shop (and the floors above above, where they lived) had been this well-known corner plot, below, that was later taken over by Banks & Sons. I had been sitting right opposite this shop (in Betty’s tearoom, for those who know!) without knowing it was my ancestral home. It took a lot of research to work this out. But this is what happens when we don’t do our homework before we set off! Now I have to go back to York to step inside this lovely shop. Luckily, visiting York is never a chore.

Changes in house name can be even more difficult to work with, particularly if several houses on the street seem to have changed name, and possibly more houses may have been built between the original ones.

So how can we be sure we have the right house?

Here are some ideas.

Photographs

If you’re lucky you may have an old family photo of the house. Even photos of people standing outside a property may provide visual clues in the form of distinctive architectural features. You can then use Google Street View to ‘walk’ along the road to find the property, if it’s still there.

Family and Local History groups on Facebook are also extremely useful for identifying the exact location of a photograph. I once witnessed someone posting an ancestral holiday snap and asking if anyone knew where in the world it could be. Within fifteen minutes it was identified as beneath a specific lamp post in a named piazza in Rome!

It’s also worth exploring whether there’s a website with old photos of your area of interest. The best one I know is Leodis, a photographic archive with over 62,000 images of Leeds, managed by the Local and Family History team at Leeds Libraries. I have found many old images of houses my ancestors lived in on there – in streets that now no longer exist. If you know of such a website for any of your areas of interest, please do share in a comment.

Maps

Mention has already been made of Google Street View. Modern day maps – including Google and other online maps – can be scrutinised alongside historic maps. My go-to place for online Ordnance Survey maps is here: https://maps.nls.uk/os/ I’ve written before about their Side-by-Side maps, but there are many other features. Something you could do is find a detailed historic map (the 25 inches to one mile series if possible) on the nls site, and see if you can compare the shapes of buildings then to existing buildings on satellite view now.

‘Walking the route’ with the census enumerator

With no photos and only documents to go on, it may be possible, using modern and contemporary maps, to ‘follow the route’ of a census enumerator. Using landmarks and occurences of smaller streets, you may be able to find the house, or at the very least to work out its general whereabouts, even if it’s not possible to narrow it down to a specific property.

Getting to know the neighbours

Using census returns for the street where your ancestors lived, it might be possible to track any changes in housenames or numbers of specific families whose occupation spans two or more decades. If the Jones family live at number 42, the Smiths at 44 and the Browns at 46, and then ten years later the same three families are at 58, 60 and 62, it is more likely that the numbering has changed than that all three families relocated together further along the same street. You can do the same thing far more accurately by consulting Electoral Registers. In the example above of my clients’ house starting out as Number 3 and eventually becoming Number 21, I could see from the Electoral Registers that this change happened in 1931. However, Electoral Registers are often not accessible online, meaning this may be something you could do only when you arrive in the area. Local archives and central libraries will usually have these registers.

What if your family’s presence predates the census?

Below is part of Starbotton, in Upper Wharfedale, where my period of interest, before 1750, predates the census. Before going I ‘walked the route’ using Google ‘Map View’ on one device and ‘Street View’ on another to be sure to cover the whole village. By the time I visited, last summer, I knew this small village like the back of my hand. However, I had no idea which house had been owned by my 8x great grandparents and later their son, my 7x great grandfather. Apart from church records and similar, indicating that the family lived in ‘Starbotton’, I was very lucky to come across a collection of property reports made over the years by the Yorkshire Vernacular Buildings Study Group. These, in turn, drew upon other property documentation at the County Record Office. I was able to identify several specific houses formerly owned by my wider ancestral family in Starbotton, and to pay special attention to them when I visited. I never did find out where my 7x and 8x grandparents lived, though, and it’s possible their house may no longer be standing. However, I can name the late seventeenth century inhabitants of around half of the properties, and I know that most of mine lived in the part of the village pictured below.

When you arrive

If the occupants were in the garden I would probably chat to them, tell them about my connection and ask permission to photograph the house from the street. If they wanted to know more about who lived there I would tell them. If they were not there I’d take the photos anyway. Just taking a few photos, wandering up and down the street, touching the wall… I find all these things bring me closer to my ancestors who lived there.

If your ancestors had a shop or public house, if the school they attended is now a business centre, or if for some other reason their former home or premises are open to the public, it would be lovely to step inside and spend a little time there.

I also enjoy seeing historic buildings and landmarks that my ancestors would have known, and just getting a feel for the area and the local history. You can do this even if the house they lived in is no longer there.

Depending on the size of the place you’re visiting, and its historic importance or embracing of tourism, you might be able to pre-book a tour with an accredited guide.

If you can’t get there

It really does make a difference going there, but if that’s not possible, just doing the research outlined above will leave you knowing a great deal more about your ancestral homes and the localities they lived in. You can also take a screen shot of your ancestral properties using Google Street View, and of course connect with online and local groups to find out more and see if anyone has any photos.

*****

If you have other ideas please do leave a comment.

![Extract from burial register, 1663. The extract is in seventeenth century handwriting and reads 'South Ile Will[ia]m Clareburne de Westgate buried eodem die'](https://englishancestors.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/william-clareburne-burial-1663.jpg?w=1024)