Several weeks back I wrote about getting started with using AI for genealogy. Today I have a couple of examples of my own experimenting with using Artificial Intelligence. As emphasised in that previous post, I have some definite red lines: I have mixed feelings about AI and am unhappy about its use in faking information. I’m also not interested on any level in having AI do the writing for me. I enjoy the writing part; but you may not, and that could be something for you to explore.

Generating an image from a physical description

My first experiment is to use a very detailed physical description of a long-deceased family member to try to create an image. Ideally, I would have both a very detailed official physical description and also a photograph of the same person so I can compare. A number of men in my direct line and siblings of direct line served in the British forces, and I do have photos of most of them. However, the physical descriptions are quite sparse. I also have physical descriptions of two ancestral family members who were in prison. One of these is accompanied by a photo dated around 1870 but again the physical description is quite minimalist. However, the physical description attached to the file of an ancestral cousin who was transported is amazing. His name is Benjamin Lucas. The description was written in 1834 and Benjamin died in 1840, so there is unfortunately no photograph to confirm or otherwise the accuracy of any resulting images.

This is Benjamin’s description. It is the fullest description I’ve ever seen on any prison or army record.

This is the text I used to generate the image: “Poor man age 43, dressed in clothes of 1834, with fresh complexion, small head, reddish hair and beard, oval face, medium high forehead, very light eyebrows with wrinkles between, grey eyes, large nose, medium wide mouth, small chin.”

I intended to use several free ‘text to image’ AI generators but found some difficult to navigate or unable to process such a lengthy instruction. I didn’t want to pay for any app at this experimentation stage. Eventually I achieved two initial images using Adobe Express. See below.

What do you think? I think the first one looks like Jean Valjean long after he was prisoner number 24601, when safely installed in Montreuil-sur-Mer as the mayor, but facially, and in poorer clothes – perhaps he could be my Benjamin.

Or this one?

I then changed the wording slightly to separate out the reddish hair and the reddish beard, leaving all other text the same. This was the result. I think he looks too young and, based on my research, lacks Benjamin’s disenchantment with life and his smoking and alcohol habits.

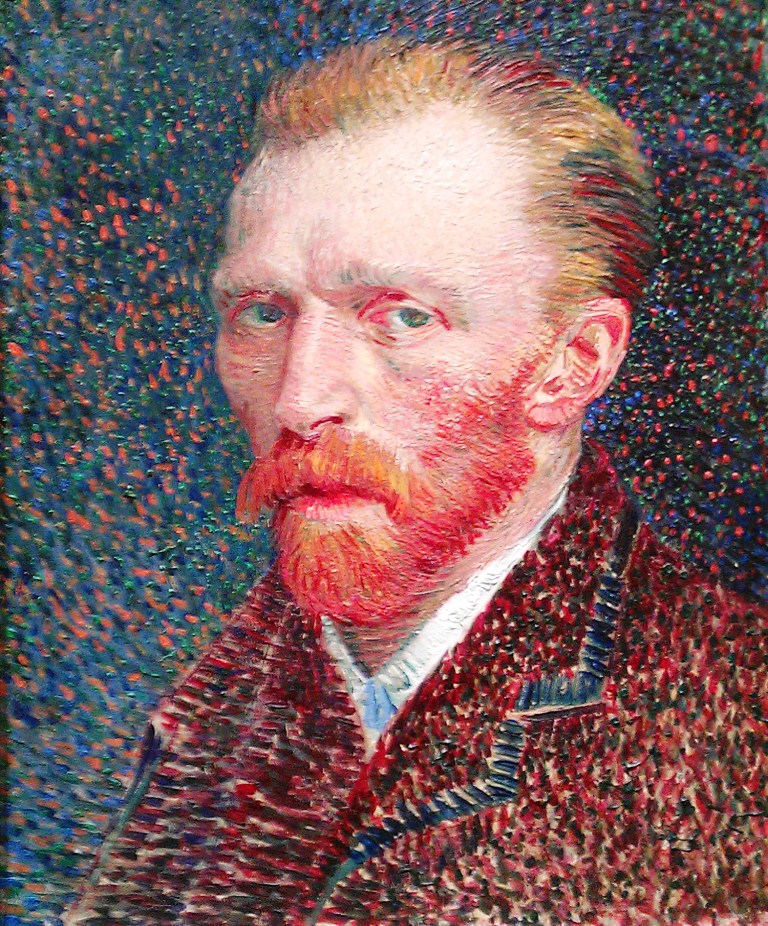

In my mind, before doing this, my image of Benjamin looked like these self-portraits of Vincent Van Gogh, only with less obviously red hair. Vincent was only 37 when he died, so just six years younger than when Benjamin’s physical description was noted. There is a ‘furtive’ look here that I like.

In this second self portrait by Van Gogh I homed in on the ‘haunted’ expression. Earlier, practising with a different app on my iPad, I asked for generation of an image based on this portrait ‘but with less defined cheekbones’. I was told my request contravened user standards! Oh dear…. I feel like a marked woman!

I don’t know what to make of this, and I don’t really see a use for it in my own research, but perhaps you will. See, what I really want is the face of Jean Valjean at the top, wearing the clothes of Van Gogh and his grey hat, and with the furtive look of Vincent #1 and the world-weariness of Vincent #2.

There’s a Canadian programme we’ve been watching via ‘Walter Presents’ on UK Channel 4 called The Sketch Artist (original French title ‘Portrait-Robo’) who achieves impossibly accurate images of perpetrators using AI, targetted questioning and her own artistry, and I was hoping for similar results, but there you are… she is a fictional TV character and I can’t compete. 🙂

Using AI to transcribe historical documents

I will admit to having high hopes for this, but my initial experimentation came to nothing! Neither of the two seventeenth century documents I uploaded could be transcribed. 😦

This is going to take more research on my part, and I’ll return to it in a future blog post when I’ve done that. In the meantime, if you’ve had success with using AI for transcriptions, any website or App recommendations will be very useful and much appreciated.

Finally, an example that turns using AI on its head

As part of a project called The Material Culture of Wills, a team at Exeter University is inviting volunteers to work alongside them in the transcription of 25,000 wills dating from 1540-1790. The research aims to explore how ownership of and attitudes towards objects changed during this period of economic transformation. However, the opportunity is also being seized to ‘train’ AI to read archaic handwriting, creating a huge data sample that will be available to the public. Volunteers are invited to proof read the work of the AI. You can find out more about it [here] and get started with proof reading. At the time of writing this, progress is well under way but very little on the earlier documents.

You can see [here] an example of what volunteers are being asked to do. The line underscored in red has been transcribed, and that transcription is shown below. You are asked to check the transcription and either agree it or amend it. If you can’t do it you simply refresh the page and get a different image. It’s quick and easy to do and you can do as many or as few as you like in whatever time you have available. The system gives the same image for checking to several volunteers, so there’s no need to worry about making an odd mistake. This is not using AI for yourself, but rather in helping AI to create better transcriptions (e.g. it is currently having trouble using capital letters) you will be practising your own paleography skills.

***

I’d be very interested to hear if you have successfully used AI for your own genealogy research, or if you’ve had success with different apps and packages from the two I’ve mentioned above. Please leave a comment if you have.