In my last post, about Ryan Littrell’s book ‘Reunion’, I pointed out that while reading it, I was aware of the limits of my own knowledge of Scottish history. A few years back I read Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander novel, and now realised these two books cover some important common ground. I knew I would understand both stories better if I learned more about this history.

Key to both was Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites. While appreciating that Bonnie Prince Charlie was the son of James, and the term “Jacobite” comes from the Latin ‘Jacobus’, meaning James, I didn’t know which particular James this was, nor how he fitted in with the monarchs of Scotland or England. Upon exploring all this I soon found myself back with the English and Scottish monarchs with whom I was familiar, and quickly understood not only who the Jacobites were, but also the importance of religion in this story.

It became clear that to understand the Jacobite cause we need to go back to Henry VIII; and to understand the claim to the English throne of two of the monarchs after Henry VIII, we need to go back to his father, Henry VII.

Although most Brits will have at least a sketchy overview of the monarchs of this period, I suspect many overseas researchers with Scottish, English or Northern Irish ancestry may not. It occurred to me that not only was this essential background to the origins of the Jacobite movement, but also to much legislation and associated documentary requirements that we draw upon in our family history research right up to 1837. Significantly, it is in the early years after Henry VIII’s break with Rome that we have the commencement of our system of parish registers.

For all these reasons, I offer you my summary. In it, you’ll find all English monarchs from Henry VII to George I. Two themes are highlighted:

- The descent of the throne. I explain how each monarch relates to his or her predecessors and where unclear, why they were installed. Some of the choices were a bit of a stretch.

- The ever-present theme for this entire period of the Church of England versus Roman Catholicism, with a bit of Puritanism and Nonconformity thrown in for good measure.

Although only an overview, this quickly became too long for one blogpost, so I’ve divided it into two. Today’s post covers Henry VII to Charles I, ending with the onset of the Commonwealth Period (1649-1660), the period also known as the Interregnum because for eleven years there was no monarch – they were literally ‘between reigns’. In terms of understanding the Jacobites, which is where this all started, this post serves as essential background to that. The period after the Interregnum, including the Jacobites, will be covered in my next post.

Henry VII, reigned 1485-1509

Henry VII’s claim to the throne was linked, via his mother, to the House of Lancaster. His father, Edmund Tudor, was 1st Earl of Richmond. Henry, then, was the first Tudor monarch: meaning that was the ‘House’, or surname of this particular royal dynasty.

Uniting the rival houses of Lancaster and York through his marriage to Elizabeth of York, it was he who adopted the Tudor Rose as the national flower of England and a symbol of peace following the Wars of The Roses. It combines the white rose for Yorkshire and red rose for Lancashire.

IMAGE: Portrait of Henry VII, painted on 29 October 1505 by order of Herman Rinck, an agent for the Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian I, Public Domain.

Henry VIII, reigned 1509-1547

The son of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, every English schoolchild will tell you that it was Henry VIII who brought about the break of England from the Church of Rome.

We even have a mnemonic for remembering the fate of his six wives who, in order, faced the following: ‘Divorced, Beheaded, Died; Divorced, Beheaded, Survived’. In fact, as we shall see, Henry did not actually ‘divorce’ wives 1 and 4; rather the marriages were ‘annulled’; and these annulments changed the course of history.

IMAGE: Portrait of Henry VIII, date unknown. Painted by a Follower of Hans Holbein the Younger. Public Domain.

In 1509, just two months after his father’s death, Henry VIII married Catherine of Aragon, the widow of his older brother who had died shortly after their wedding. Henry and Catherine were crowned the following day. After several still-born and short-lived babies, Catherine gave birth to a daughter, Mary, in 1516.

Although Mary survived, Henry was desperate to have a son. He came to believe that his marriage was blighted on account of him having married his brother’s widow, this being contrary to Leviticus 20:21. (‘If a man marries his brother’s wife, it is an act of impurity; he has dishonored his brother. They will be childless.’) In 1625 he began an affair with Anne Boleyn. He hoped to have his marriage to Catherine annulled on the grounds that the Pope had lacked the authority to give dispensation to it in the first place, but a papal annulment was not to be. Instead, a special court at Dunstable Priory in England in May 1533 would declare the marriage null and void. By this time, Catherine had been banished from court, Henry and Anne Boleyn had married, and their daughter Elizabeth was born later in 1533. However, it was not all sunshine and roses in the royal marriage. By 1536, having failed to give Henry a son, Anne fell out of favour. She was charged with treasonous adultery and incest, and executed. Ten days later, Henry married Jane Seymour. By the Succession to the Crown Act of 1536, Henry’s daughters Mary and Elizabeth were both declared illegitimate. Any children to be born to Jane were to be next in the line of succession.

By this time, relations with Rome had worsened. The 1532 Act in Restraint of Appeals had abolished any right of appeal to Rome. Instead, the King was to be the supreme authority. By the Act of Supremacy of 1534, Henry had been recognised by Parliament as Head of the Church in England. In consequence, Pope Clement VII excommunicated Henry, although this was not formalised until 1538.

In October 1537, Jane Seymour provided Henry with a son and heir: Edward. Jane died twelve days later but Edward survived. Henry would marry three times more. His marriage to Anne of Cleves in January 1540 was annulled shortly afterwards on grounds of non-consummation. His fifth marriage to Catherine Howard ended with a further beheading two years later. Finally, in 1543, Henry married wealthy widow Catherine Parr. None of these marriages produced further children, but Catherine Parr brought about a reconciliation between Henry and his daughters Mary and Catherine. By the Act of Succession of 1543, both were restored to the line of throne after Edward. Henry died four years later, and as the mnemonic reminds us, was survived by Catherine Parr.

Although a contemporary of Martin Luther and certainly aware of his criticisms of the Catholic church, Henry VIII did not support him. Indeed, he had been a devout Catholic and had written a treatise in which he defended the seven sacraments against Luther’s criticisms. In recognition, in 1521 he was given the title ‘Defender of the Faith‘ by Pope Leo X – a title still held by British monarchs. After the break from Rome, there would initially have been little difference in church services and theology, although Henry did later adopt some Protestant reforms. Undoubtedly, though, these were motivated more by political expediency and a desire to increase his personal power than by theological concerns. To this end, Henry is remembered for the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the period between 1536-1540 when he closed and seized the assets of monasteries, priories, convents and friaries. Those who resisted were executed, as were other Catholics and indeed some Protestants who challenged his religious policies.

Edward VI, reigned 1547-1553

Henry VIII was succeeded by Edward, the son born to his third wife, Jane Seymour. Although his older half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, had been restored to the succession, Edward took precedence. He was fiercely Protestant, and during his short reign the Church of England moved further away from the practices of the Church of Rome. Edward was particularly anxious that Mary who, as daughter of the Roman Catholic Catherine of Aragon, remained true to her faith, would undo his Protestant reforms. In his hand-written Devise for the Succession, he sought to exclude Mary from the line of succession. Persuaded that he must disinherit both his half-sisters, he named his cousin, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir. Edward VI died from tuberculosis in 1553.

IMAGE: Portrait of Edward VI by William Scrots, circa 1550. Public Domain

Lady Jane Grey, reigned 10-19 July 1553

Although, as great niece of Henry VIII, Lady Jane Grey was a genuine (if unexpected) claimant to the throne, her right to it was disputed. After only nine days she was deposed, to be replaced by Mary, who had her executed in 1554.

IMAGE: Portrait of Lady Jane Grey. Artist Unknown, but it is known as the Duckett Portrait, and is believed to date from 1552. The portrait was owned by Sir Lionel Duckett in 1580. He was married to the first cousin of the wife of the first cousin of Lady Jane Grey. Public Domain.

Mary I, reigned 1553-1558

The firstborn of Henry VIII, by his first wife Catherine of Aragon, Mary was the first Queen of England to reign as monarch in her own right. She was also, from 1556 until her death, Queen Consort of Spain. Mary’s marriage to King Philip of Spain was a very unpopular move; and as Edward VI had feared, she did indeed attempt to restore papal supremacy in England. Abandoning the title for herself of Supreme Head of the Church, she reintroduced Roman Catholic bishops and set about bringing back monastic orders.

As a result of her revival of former heresy laws, around three hundred Protestants were put to the stake in just three years. Such was Mary’s fervour that her opponents labelled her ‘Bloody Mary’. Upon marriage, Mary wished to have children and leave a Roman Catholic heir who would continue her reforms, but she died childless in 1558, leaving the way clear for her half-sister to inherit the throne.

IMAGE: Portrait of Mary I. Artist and date Unknown. Public Domain.

Elizabeth I, reigned 1558-1603

Daughter of Henry VIII by his second wife, Ann Boleyn, Elizabeth, was the last of Henry’s three legitimate children to take the throne. During her forty-five year reign, a secure Church of England was established. Highly educated, intelligent and deeply devoted to the country, she held that ‘there is only one Jesus Christ and all the rest is a dispute over trifles’. She asked for outward uniformity. The Thirty-nine Articles of 1563 established the faith and practice of the Church of England, but were carefully crafted as a compromise between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism.

IMAGE: Portrait of Elizabeth I, known as the Rainbow Portrait. It has been attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts The Younger and to Isaac Oliver. It is believed to date from 1600-1601. Public Domain.

The religious question, however, did not go away. In 1570 Elizabeth was excommunicated. by Pope Pius V. In his papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, he referred to ‘the pretended Queen of England and the servant of crime’, declaring her a heretic. On pain of excommunication, Elizabeth’s subjects were released by Pius V from allegiance to her.

Following the discovery of assassination plots, harsh laws were passed against Roman Catholics. For her involvement in such plots, Mary Queen of Scots, first cousin once removed of Elizabeth, and a likely successor to her, was ultimately executed in 1587. Elsewhere in Europe there were threats of invasions. Philip of Spain (by now titled Philip II) believed he had a claim to the English throne through his marriage to the late Queen Mary I. Indeed, the purpose of the Spanish Armada was to overthrow Elizabeth and re-establish Roman Catholicism by conquest.

Choosing never to marry, and dying without issue in 1603, Elizabeth was the last of the Tudor monarchs.

James I, reigned 1603-1625

Elizabeth was succeeded by James I. James was great great grandson to Elizabeth’s grandfather, Henry VII, via his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots; Mary’s father, King James V of Scotland; and his mother Margaret who was Henry VII’s daughter. Already king of Scotland for 36 years by the time of his accession to the throne of England, he is known as James VI of Scotland and I of England, or James VI and I. The first English King of the House of Stuart, his twenty-two year reign over Scotland, England and Ireland is known as the Jacobean era.

Although baptised as a Roman Catholic, James was brought up as a Protestant. While personally reasonably tolerant on the matter of religion, he faced challenges from various religious viewpoints, including Presbyterianism, Roman Catholicism, and different branches of English Separatists. The aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 led to strict penalties for Roman Catholics.

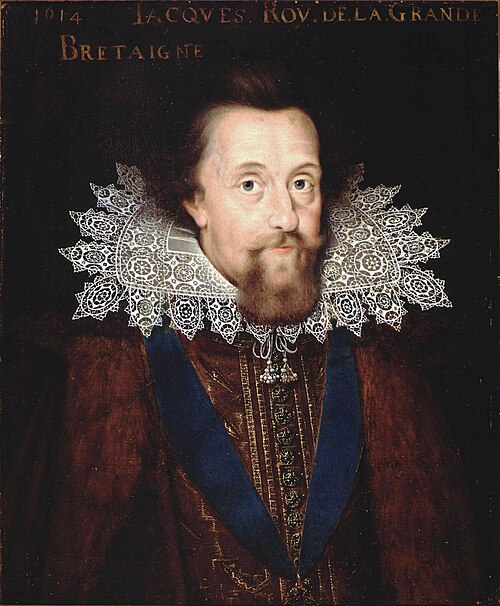

IMAGE: Portrait of James VI and I, 1614. Artist Unknown. Public Domain.

A prolific writer himself, it was James VI and I who sponsored the translation of the Bible into English, now known as the Authorised King James Bible. James also endorsed the practice of witch hunting, as set down in his 1597 publication Daemonologie. Unlike Elizabeth, whose approach to monarchy tended towards cooperation, James’s held an absolutist view of the Divine Right of Kings.

Charles I, reigned 1625-1649

James VI/ I was succeeded in 1625 by his second son Charles I. Charles was Protestant, and deeply religious. However, at a time when plainer forms of worship with greater personal piety were gaining ground, Charles favoured the high Anglican form of worship. In terms of ritual, this was the closest to Catholicism. Charles’s marriage in 1625 to Henrietta Maria, daughter of Henry IV of France added to the concerns. Having promised Parliament that his union with a Roman Catholic would not bring about advantages for those wishing to recuse themselves from church attendance on alternative religious grounds, Charles nevertheless signed a commitment promising exactly that as part of his marriage treaty.

Charles’s personal spending on the arts greatly increased the crown’s debts, bringing him into conflict with Parliament. Like his father, Charles believed in the Divine Right of Kings: his authority came from God; that of Parliament came only from Magna Carta. Therefore in 1629 he dismissed Parliament, commencing a period of Personal Rule, alternatively known as the ‘Eleven Years’ Tyranny’ which lasted until 1640.

IMAGE: Portrait of Charles I. Artist and date Unknown. Public Domain.

All this, and more, made Charles a deeply unpopular king. Riots and unrest started to spread. In 1637 he attempted to impose a High Church liturgy and prayer book in Scotland. This led to riots in Edinburgh. October 1641 saw an Irish uprising, leading to further tensions between Charles and his Parliament over the command of the Army. In August 1642, against the wishes of Parliament, Charles raised his standard at Nottingham. This symbolic act signaled the start of a Civil War, with Charles I defending his divine right to rule, and Parliament advocating for a greater say in government. By the end of the year, each side had amassed an army of 60,000 to 70,000 men, the Royalists known as Cavaliers and the Parliamentarians as Roundheads. In general, Charles enjoyed support in the north and west of England, while Parliament controlled the South and East, together with London and, significantly, most of the key ports. In 1643 Scottish Covenanters entered into an alliance with the English Parliamentarians. Key to their Solemn League and Covenant of 1643 was a pledge to work towards the establishment of Presbyterianism in England. The intervention of the Scottish was almost certainly key to the eventual success of the Parliamentarians, and the Battle of Naseby, 1645, proved to be the turning point.

In 1646 Charles was captured and imprisoned. On 30th January 1649 he was beheaded. The eleven-year Interregnum had begun.

Pedigree Chart – the story so far: Henry VII to Charles I

This is, necessarily, a whirlwind tour. If you’d like to read a little more about each of these monarchs (and the ones who came before and after), you’ll find a good introduction at the Royal UK website. For more detail, go to the Wikipedia page for each. For more than that, you’ll need to explore more scholarly texts.

My next post will move on from here, and we’ll see where the Jacobites fit in.