This is the third in my ‘Ancestral Tourism’ series, and follows on from posts about preparing for visiting Churches and Churchyards and Public & Municipal Centuries featuring in our ancestry. In those previous posts, the focus was on knowing the history, finding the records and then finding any maps of the churchyards and cemeteries. In this post we’re going to be ‘reading’ the burial ground. What can we deduce from the location, the headstone (or absence of a headstone), the symbolism and anything else that will give us clues as to our ancestor’s life and social standing?

Please be prepared before applying what follows to your own family that there is a possibility that not all your ancestors will have well-kept headstones in peaceful and picturesque settings within the churchyard or cemetery. Some may have been buried with unrelated people in common graves, with or without a headstone. This is part of their story, and the story of the times in which they lived, but it can be upsetting to find.

Consecrated or Unconsecrated?

As outlined in my last post, from the middle of the nineteenth century the Burial Acts required that half of any new Municipal or Public cemetery was to remain ‘unconsecrated’. The other half would therefore be ‘consecrated’. What does this mean?

Consecrated

- Dedicated to a sacred purpose; made sacred; hallowed, sanctified.

- Dedicated, ‘sacred’ to a tutelary divinity.

- figurative. Sanctioned by general observance or usage.

Although the online Oxford English Dictionary gives the above definition, in relation specifically to burial grounds in England and Wales it is a centuries-old term referring to land that has been blessed and set apart for Christian burial according to the rites of the Church of England (in Wales now, Church in Wales). ‘Unconsecrated’ referred to any portion not blessed or made sacred according to those rites. Before the mid-1800s, when most burials took place in the graveyard of the parish church, the official burial had to be conducted by an Anglican clergyman in accordance with the Church of England prayer book service. This applied even to those who had, in life, followed different religious practices. However, such people were not eligible for burial within the Consecrated area of the graveyard. They were buried in a separate Unconsecrated section. This applied also to babies who died before they were baptised and, before 1823, to suicides.

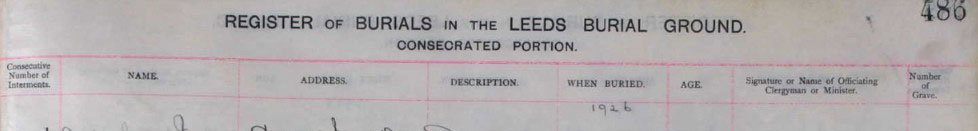

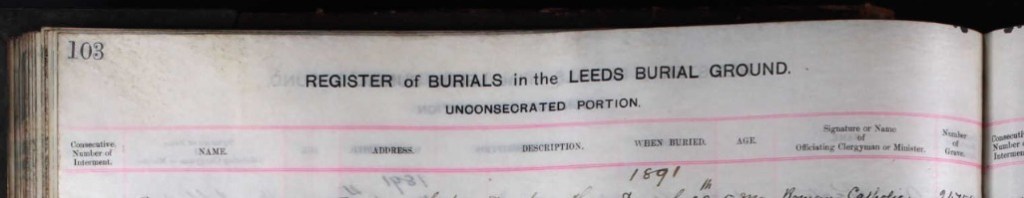

Also mentioned in my last post, the development of the new Public Cemeteries from the 1820s and Municipal Cemeteries from the 1840s coincided with a greater acceptance and recognition of different religious practices. Here, the term ‘Consecrated’ was kept but now, in the ‘Unconsecrated’ portion of the cemetery, the burial service itself was likely to have been carried out in accordance with the rites of the deceased’s religion. Today there is greater recognition of the different rites and practices developed by different religions and cultures in commemorating their dead. Although some dedicated cemeteries exist, there are also separate areas for specific faiths within public cemeteries. However, back when our ancestors were being buried it was simply ‘Consecrated’ or ‘Unconsecrated’, and eventually over time the terms ‘Anglican’ and ‘Nonconformist’ came to be used. Although in England and Wales today we use the latter term for Protestants who are not part of the Church of England, in earlier times it was used for anyone whose religious beliefs differed from the established church, the Church of England. It therefore referred also to Roman Catholics, for example. As can be seen from the image above and that below, separate registers were kept for these two sections of the cemetery.

Follow the clues

Finding your ancestor in one or the other may come as a surprise. If so, this is extra valuable information about your ancestors. Precisely what it tells you will depend on the context. For example, all in the same cemetery:

- My Irish-born 2x great grandfather’s burial is recorded on the very page you see above. He was buried in the Unconsecrated part because he was Roman Catholic.

- My 4x great uncle’s burial is also in the Unconsecrated part. This is because he and his family worshipped at the Wesleyan chapel.

- I had a question mark about the denomination of an ancestor from Ulster. He was buried in the Consecrated portion of the cemetery, but his first child with his English, Anglican, wife was baptised in the Roman Catholic church. His burial seem to settle the question… or did it? There remains the possibility that he was simply not a church goer, and by the time of his death his adult children just didn’t know he was actually Roman Catholic.

- The burial of another 2x great grandfather in the Anglican part of the cemetery in 1898 was interesting because he took his own life. This gave me a reason to research the burial of suicides. Suicides had traditionally been buried at a crossroads, sometimes with a stake through the heart. The Burial of Suicides Act, 1823, banned such practices. It permitted burial of suicides in consecrated ground, but only at night and without a Christian service. With the passage of the nineteenth century came a greater understanding of mental health, and the term ‘Of unsound mind’ came to be used by Coroners. In 1882, the 1823 Act was repealed, and replaced with the Internments (felo de se) Act. This permitted the burial of those who had taken their own lives at any hour and with the usual religious rites, including in a churchyard at any hour. However, suicide would not be decriminalised until 1961.

Burying in style!

There were great differences between the funeral and burial practices of rich and poor. For the wealthy, this could be a no-expense-spared event from start to finish: an opportunity to be seen to be ‘doing things properly’ according to the etiquette that had grown up around funerals. Obituaries in the newspapers will give you an idea of the size and scale of a grand funeral.

In the cemetery there are more clues. These include the location of the grave. A prime position with good views cost more. It may also have been possible to pay extra for a nine foot deep grave rather than the usual six feet, although you won’t be able to see that from the grave itself. A deeper burial was thought to help preserve the body.

A range of funerary monuments were also available, ranging from mausolea, cenotaphs, tomb chests and sculptures to headstones and more simple marker stones. Historic England have produced a guide to Caring for Historic Cemetery and Graveyard Monuments which includes descriptions of the various types.

If you’d like to know more about a whole range of roles, customs and traditions linked to death and funerals, Friends of Beckett Street Cemetery in Leeds have compiled an excellent overview of Victorian funeral traditions and etiquette. Some of these would have been de rigeur amongst the wealthier folk but others applied more widely. Even when I was growing up I remember people closing the sitting room curtains after a death in the home.

Symbolism

Victorians loved symbolism, and the various monuments and gravestones were the perfect canvas for this form of expression. On their website, Arnos Vale Cemetery, Bristol, make the point that when larger public cemeteries started to appear, much of the population was not literate. The symbols found on graves made them more meaningful for someone who may not be able to read the words. Even today, if we understand the symbolism, a whole new layer of understanding opens up to us as we walk amongst the gravestones. Perhaps there might be clues on the gravestones of some of your ancestors, letting you know what was important to them and their loved ones. You might even come across some symbolism pointing you to membership of the Freemasons or similar, which would then open up a new line of research for you. The Funeral Directors association and Family Tree Magazine have also published useful lists of symbolism and meanings.

It was a surprise to walk around Ryde Cemetery after reading them and to note the symbolism on a lot of the stones and monuments. This ‘broken’ column represents a life cut short, and the anchor symbolises EITHER hope, steadfastness, and the secure connection to God or eternal life OR a seafaring life, perhaps with the Navy – or perhaps both. Since Ryde is on an island, either is possible and now I’m thinking I should have spent longer and read the inscription to find out more…

Different types of grave

For those with the ability to pay for a private grave, there were:

- single plots, intended for one person in a coffin

- companion plots, intended for a couple, perhaps side by side

- family plots, where several members of the same family can be buried together.

A certificate or “grave paper” documented the purchase. (I have one of these, purchased by a 2xG grandfather on the death of his wife in 1875.)

A purchased plot does not necessarily mean our ancestors will also have purchased a headstone, so you may need to navigate to your ancestor’s final resting place with the aid of only the plot number and a site map. The location of such plots, amongst others with headstones, should enable you to differentiate them from the common graves detailed below.

One of the motivations for the publicly-funded Municipal Cemeteries was the ability to provide for all social levels, including some lower cost options so that the labouring classes could afford to bury their dead with dignity.

A Common grave was a plot that belonged to the cemetery, not an individual or family, and was used to bury unrelated people. There were several different types of common grave, and the costs for the different types varied:

- Lock-up graves: these were the cheapest type of grave. They were filled over the course of a few days as more bodies became ready for burial. Between each burial the soil was not replaced. Instead, a wooden ‘door’ was locked in place over the grave. When the grave had the required number of deceased people, the earth was piled on top. These were also called Open graves.

- Public graves: like lock-up graves, these were filled up as newly deceased unrelated individuals became ready for burial. The difference is that these graves were refilled with earth after each new burial. They were therefore a little more expensive.

- Note that ‘Pauper’s grave’ was not an official term and probably more rightly refers to the burial administration rather than to the grave itself – a Pauper’s burial. Essentially, before 1834, paupers were buried at the expense of the parish, and after that at the expense of the Board of Guardians. There was no unnecessary expense. The actual grave would have been one of the above types of common grave with no inscription, probably a lock-up grave where that was an option. Local authorities remain responsible today for the burial of a deceased person leaving no funds for a funeral and no one else to arrange it.

- Inscription graves: For a small additional fee, a deceased person could be buried in a common grave but with a headstone inscribed with the name, date of death and age of every occupant. Some of the headstones may have had bodies arranged on both sides with inscriptions on both sides of the stone. These are a feature of the municipal cemeteries in Leeds – in fact every reference I have come across online relates to Beckett Street or another of the Leeds cemeteries. Here, they are known as ‘Guinea Graves’, that being the original cost of burial in one of these Inscription graves. If you are aware of this type of grave (Inscription or Guinea Graves) elsewhere in the country, please leave a comment saying where and by what term they are known – thanks.

Some notes

For overseas readers (or very young British readers, perhaps!), a guinea was a British coin, originally minted in 1663 with a value of £1 (One Pound). Eventually it came to have the value of £1 – 1 s (One pound one shilling, i.e. 21 shillings). Even after the guinea coin ceased to circulate, the term remained as a unit of account worth 21 shillings. As late as the 1970s it was used for the quoting of professional fees and luxury items.

I have previously written about how to ‘read’ a Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery [here].

*****

I have become rather more fascinated with municipal cemeteries than anticipated! My next post will be about getting the most from different cemetery records, before returning in the post after that to Ancestral Tourism: houses and places our ancestors knew.

![Extract from burial register, 1663. The extract is in seventeenth century handwriting and reads 'South Ile Will[ia]m Clareburne de Westgate buried eodem die'](https://englishancestors.blog/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/william-clareburne-burial-1663.jpg?w=1024)