In my last post I explained how a desire to understand more about the Jacobites led to the compilation of an overview of all English/ British monarchs from Henry VII to George I. I wanted to understand:

- The descent of the throne: how each monarch relates to his or her predecessors and where unclear, why they were installed.

- The role of religion in decisions about the Crown, as well as attitudes towards Roman Catholics, Puritans and Nonconformists during the reign of each monarch.

- What connection this had with the Jacobites.

- And finally – although to be honest this was something that piqued my interest during the research rather than something I set out to do – how this connects with certain documentation we might come across as family historians.

This is the second part of my exploration. The first post covered Henry VII to Charles I. This post starts with the Interregnum followed by the Restoration of Charles II, and ends with George I. It is of course a quick overview focusing just on the above, not a learned analysis!

Interregnum, or Commonwealth Period

Part 1 of this overview ended with Charles I, who was beheaded in 1649, the act which started the Interregnum. Reading about Charles, we understand there were a number of tensions leading to the civil war and ultimately the Interregnum. One of these was Charles’s religious position. The Church of England was sandwiched between the high ceremony of the Roman Catholic church and the Puritans, who wanted a simpler form of worship. Charles, however, favoured a ‘high church’ within the Church of England. His marriage, too, to the Catholic Henrietta Maria, raised concerns among Protestants. On top of this, Charles’s belief in the Divine Right of Kings exaccerbated both religious and political tensions. Parliamentarians, many of whom were also religious reformers, were angered by Charles’s favoritism towards Catholics. They sought to limit his power and influence, not only on religious matters but also more broadly, since Charles often clashed with, overruled and even dissolved his Parliament for an eleven-year period.

In light of all this, following the execution of Charles I, England was declared a Republic. Initially Member of Parliament for Huntingdon, Oliver Cromwell rose to prominence as leader of the Parliamentarians and ultimately ruled as Lord Protector. The Commonwealth period was a time of great religious and social change. Cromwell wanted to establish a more just and equitable society. Yet he was a devout Puritan who believed this would be achieved through spiritual and moral reform. During this period the Church of England was disestablished,the House of Lords abolished, and Puritanism gained prominence. Many restrictive laws were passed to regulate moral behaviour. Theatres were closed down, strict observance of the Sabbath was required, and celebrations of Easter and Christmas were banned.

Charles II, reigned 1660-1685

After the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Scots viewed his son, also Charles, as his rightful heir. Wishing to maintain a monarchy in Scotland and England, they invited him to Scotland. The young Charles had been sent to safety in France – not only the homeland of his mother, but also the realm of his uncle, Louis XIII. In 1643 the Scottish Covenanters had entered into an alliance with the English Parliamentarians, including a pledge to work towards the establishment of Presbyterianism in England. Now the Scots, particularly the Covenanters, viewed Charles II as a potential leader who could uphold Presbyterianism in the three kingdoms (Scotland, Ireland, England). In accordance with their wishes he signed the National Covenant, affirming Presbyterianism as the official religion in Scotland. On 1 January 1651 Charles II was crowned by the Scots at Scone – the last coronation to take place in this historic Scottish coronation site. However, a few months later, the decisive defeat of the Scottish army broke the power of the Presbyterians in England and Scotland, ending the relevance of the Solemn League and Covenant. Once more, Charles was granted sanctuary in France, and the English government announced that henceforth, England and Scotland were to be one Commonwealth.

After Oliver Cromwell’s death in 1658, there was a desire to restore the monarchy. The first election returned a government that was fairly evenly divided on political grounds between Royalists and Parliamentarians, and on religious grounds between Anglicans and Presbyterians. In 1660, after signing the Declaration of Breda, Charles was invited to London and restored to the throne as Charles II. Through the Declaration, Charles promised those who recognised himself as monarch a general pardon for crimes committed during the Civil War and the Interregnum. Most of Cromwell’s supporters were granted amnesty, but fifty were not. Nine were executed, the others given life imprisonment or excluded from office for life. Cromwell’s body was posthumously decapitated. Charles also promised religious toleration, with liberty of conscience. Finally, he promised to rule in cooperation with Parliament.

Image: King Charles II

by John Michael Wright, c. 1660–1665 National Portrait Gallery, London

Source: Wikipedia, Public Domain

However, after elections the following year, a new overwhelmingly Royalist and Anglican Parliament was sworn in, bringing with it a series of limits to the religious toleration with which more advanced genealogists will be familiar. These included a requirement for municipal officeholders to swear allegiance, the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the Conventicle Act of 1664, which forbade religious gatherings of more than five people outside the Church of England, and a prohibition for clergymen who had been expelled from their parishes for church services not conforming to the newly enforced Anglican requirements from coming within five miles of that parish. As Puritanism lost its momentum, theatres reopened and as a release from the restrictions of the Commonwealth period, bawdy ‘Restoration comedy’ became a recognisable genre. For the first time, female actors were required to play female roles. The Restoration was therefore a time of great social change.

Charles II, however, had family arrangements that placed him very much at conflict with limits on religious tolerance. On 21st May 1662 he married Catherine of Braganza, the Roman Catholic daughter of King John IV of Portugal. The marriage was celebrated in two ceremonies at Portsmouth – a Catholic one, conducted in secret, followed by a public Church of England service. It’s worth remembering here that Charles II’s mother, Henrietta Maria, was also Roman Catholic, that Charles had spent most of his life in exile in France, and that Louis XIV of France was his first cousin. In 1670, by treaty agreed between the two cousins (The Treaty of Dover/ Secret Treaty of Dover), Charles committed, amongst other things, to convert to Catholicism at some point in the future. In return, he would receive a secret pension from Louis that he hoped would give him some freedom from Parliamentary scrutiny of his finances. He would also receive a financial bonus from Louis plus the loan of French troops to suppress any opposition when his conversion was made public. The Treaty remained a secret, and Charles never did convert. However, against the wishes of Parliament, he did issue the Royal Declaration of Indulgence of 1672, by which he attempted to suspend laws that punished recusants from the Church of England, thereby extending religious liberty both to Protestant nonconformists and to Roman Catholics. The following year he was compelled by Parliament to withdraw the Declaration.

Charles died in 1685. Having no legitimate children, he was succeeded by his brother.

James II of England/ VII of Scotland, reigned 1685-1688

Like his older brother Charles II, James had lived in exile in France during the Commonweath period, and served in the armies of Louis XIV until the Restoration in 1660. However, in 1669 James had converted to Roman Catholicism. There had therefore been concern at the prospect of his acceeding to the throne, but on the whole a hereditary succession was viewed as preferable to the possibility of a further republican commonwealth. It was, in any case, considered that the reign of James II / VII would be merely a temporary Catholic interlude. By his first marriage to Anne Hyde, James had one son who died, and two daughters. At the insistence of their uncle Charles II the daughters, Mary and Ann, were raised in the Church of England.

In 1687 James II/ VII issued the Declaration of Indulgence. As with the 1672 Declaration issued by his brother, this was an attempt to promote religious tolerance by suspending penal laws enforcing conformity to the Church of England, allowing people to worship freely in their homes or chapels, and ending the requirement for oaths of allegiance for government office. However, in a period when fear of Catholicism was widespread, he had already made enemies of Anglican bishops as well as Lords and Members of Parliament, on one occasion in 1685 proroguing Parliament and ruling without it. He then continued to promote the Roman Catholic cause, dismissing judges and others who refused to support the withdrawal of laws penalising religious dissidents and preventing the appointment of Catholics to important posts in academic, military and political positions. By 1688 most of James’s subjects had been alienated.

Image: King James II and VII

Artist unknown.

Source: National Portrait Gallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In April 1688 James II/ VII reissued the Declaration of Indulgence. Two months later his second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a son and heir: James Francis Edward. The baby was baptised according to the rites of the Roman Catholic church. It was a final straw: fearful of a Roman Catholic dynasty in the making, on 30 June 1688 a group of Protestant nobles invited William of Orange to come to England with an army. When William arrived on 5th November 1688, many army officers defected, joining him against the king. The following month James II/ VII fled with his wife and baby son to France, where he was received by his cousin Louis XIV. This overthrowing of James II/ VII is what is referred to as The Glorious Revolution, 1688-89.

The descent of the throne is about to get very complicated!

William III (reigned 1689-1702) and Mary II (reigned 1689-1694)

We have already met William and Mary. Mary is the oldest daughter of James II and VII, by his first wife Anne Hyde. It was mentioned above that at the insistence of their uncle, Charles II, Mary and her younger sister Ann were raised in the Church of England. Charles also arranged for Mary to marry the Protestant Prince William of Orange – that same William who arrived in 1688 by invitation of the Protestant nobles to overthrow the King – that King being his father-in-law.

In fact not only Mary but also William of Orange had a claim to the British throne. Both were grandchildren of Charles I. William was descended from Charles I through his mother, Princess Mary, who was the eldest daughter of King Charles. The soon-to-be queen Mary, as we have seen, was descended from Charles I via his second son James II and VII.

Image: William III and Mary II

Painting: Sir James Thornhill; Photo: James Brittain derivative work: Surtsicna (cropped)

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1689, it was declared by Parliament that James had abdicated by deserting his kingdom. William and Mary were offered the throne as joint monarchs but were required to accept a Declaration of Rights, later enshrined in the Bill of Rights of 1689. The Statute remains a cornerstone of English constitutional law, setting out basic civil rights, resetting the relationship between monarch and Parliament, providing guarantees against the abuses of power that had become commonplace, and changing the succession to the English Crown. James II / VII and his heirs being now excluded from the throne, this exclusion was extended to apply to all Roman Catholics. The Toleration Act of the same year allowed for freedom of worship for dissenting Protestants, but not to Roman Catholics or Jews. ‘Tolerance’ only went so far. Nonconformists were required to swear oaths of Allegiance and Supremacy, they continued to be excluded from holding political offices and positions at universities, but they could meet to worship as they wished, provided they did so in registered meeting houses and with licensed dissenting preachers. However, it was better than the previous position and was considered a reward for Protestant dissenters who did not support James II / VII.

Mary reigned until her death in 1694; William continued until his death in 1702.

Anne, reigned 1702-1714

Leaving no children, William and Mary were succeeded by Mary’s sister Anne, who reigned until her death in 1714. When she, too, died childless (her only surviving son having predeceased her), the line passed to Sophia, Electress of Hanover, who was the granddaughter of James I/ VI via her mother Elizabeth, and was the nearest Protestant relative.

Image: Queen Anne

Artist unknown, 17th century

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

George I, reigned 1714-1727

In fact Sophia had died two months before Queen Anne, meaning the line passed to her son, George Ludwig. Although there were around fifty Roman Catholics who would have had a stronger claim were it not for the exclusion, George I acceeded to the throne in 1714. The reign of the House of Hanover, which would continue in the United Kingdom until Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, had commenced.

Image: George I

Artist: Godfrey Kneller

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

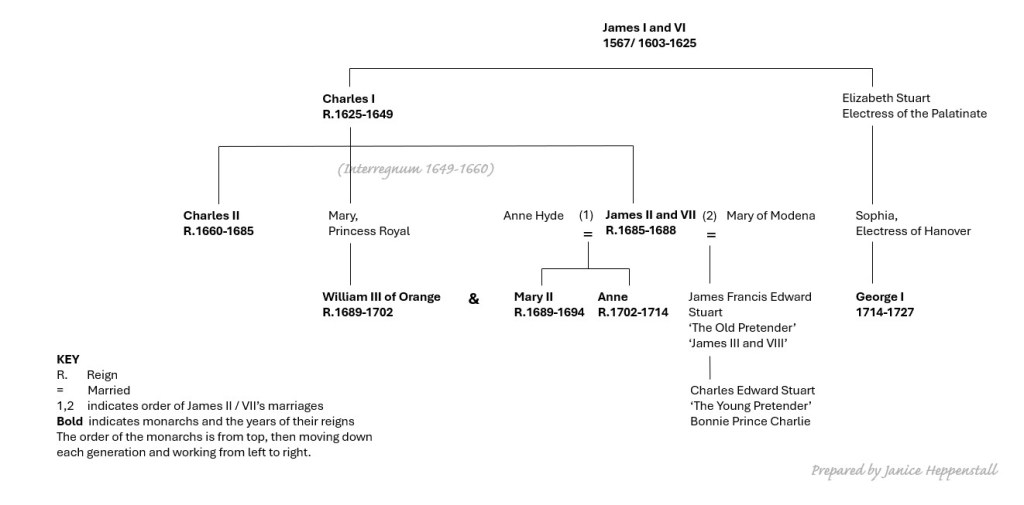

Pedigree Chart

In the following chart you can see all the monarchs mentioned in the above account, together with the others mentioned as essential to the line of descent. There are also two more people, descended from James II and VII and his second wife Mary of Modena. We will now turn to look at them.

The Jacobites

Were it not for the exclusion of Roman Catholics from the succession to the English Crown, one of the people who would have had a stronger right to the throne than George I was of course the son of the exiled James II / VII. The old king had died in France in 1701; and his son, James Francis Edward Stuart, who had been created Prince of Wales in July 1688, considered himself James III and VIII.

Following the coronation of George I – who spoke very little English and whose loyalties and thoughts were primarily with Hanover – riots and uprisings broke out in various parts of the United Kingdom.

‘Jacobites’ had been active since The Glorious Revolution. They sought to restore the Stuart line to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland, but the reasons for their support were complex and varied. A central tenet of Jacobitism – the political ideology behind the movement – was that kings were appointed by God, and therefore the post-1688 regime was illegitimate. This view was particularly strong amongst the Episcopalians in the Lowlands. There was also opposition to the Act of Union of 1707. Many Jacobites believed the Stuarts would reverse the Union and restore Scottish independence. Akin to this were clan loyalties and traditions, and the enduring sense of marginalisation by the English and British government. Consequently, in Scotland, Jacobitism was strongest in the Western Highlands and in Perthshire and Aberdeenshire. However, given the origins and connections between the Scottish clans and Ireland, there was a Roman Catholic element to the support too, and indeed Jacobitism was also strongly supported in Ireland. There were also pockets of support in Wales and parts of England; and the Stuarts received some backing from France and other countries.

After an unsuccessful invasion in 1715 James – the would-be King James III/ VIII, nick-named ‘The Old Pretender’ – lived in papal territory, and from 1718 until his death in 1766, resided in Rome. Here, he established a court-in-exile, creating Jacobite Peerages and operating an unofficial consulate. In 1719 James married Maria Clementina Sobieska, with whom he had two sons. The second son, Henry Benedict Stuart would become a Cardinal of the Catholic Church. The first, born 31st December 1720, was Charles Edward Stuart. We know him as ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’. He was also nicknamed ‘The Young Pretender’. It was Bonnie Prince Charlie who led the Jacobite Rising of 1745, culminating in the Battle of Culloden.

Armed with all of the above information, the Scottish history outlined in Reunion will make more sense. You will also be well-prepared should you wish to tackle Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander! However, I hope it will also be of use in understanding the odd document you’ve found in your own family research. For example, I now understand what was behind a document countersigned by my 7x great grandfather at York Castle in 1745 pledging allegiance to the king (George II) against the ‘Rebellion in Favour of a Popish Pretender’.

It has been quite time-consuming to put this together. I had never had a great deal of interest in the Kings and Queens of England/ United Kingdom; my personal interests lie with the ordinary people. However, working on this has given me a great context within which to place all of the changes in attitudes and leniency towards Nonconformists in the 1660s, 1670s and 1680s – and this is a period when a number of my own ancestors were converting to Nonconformist practices. I even looked at a chart of Kings and Queens of England last week and was able to spot immediately that Lady Jane Grey was missing! I hope you will find it interesting and useful too.