I’ve wanted to visit the Back to Backs Museum in Birmingham for several years, and finally last week had the opportunity to do it.

Maintained and operated by the National Trust, the museum is located at the junction of Hurst Street and Inge Street, about ten minutes’ walk from New Street Station. On the map below – surveyed in 1887 – I have outlined the exact location and extent of the museum.

The ‘museum’ is actual nineteenth century housing. Building commenced in 1802, and by 1831 what we see on the map was complete. The three houses fronting onto Inge Street were numbers 51, 52 and 53, although the numbering seems to have changed over time. Initially known as Wilmore’s Court, the courtyard is accessed via a passage between two of the houses, and would become known as ‘Inge Street, Court 15’

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

CLICK HERE for link to original on nls website

Back to back housing is a particular interest of mine. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, all of my family lived in back to backs. The difference was that as the nineteenth century progressed, there had been an acceptance that the arrangement of back to backs around courtyards was unhealthy – particularly as such housing was generally of poor quality and included very unhygienic shared toilet facilities. Hence back to back housing in Leeds came to be built in rows of parallel streets, making a huge difference in terms of airflow and the health benefits flowing from that.

If you have ancestors living in urban areas, particularly in the rapidly-growing industrial towns like Leeds, Manchester, Liverpool and of course Birmingham, you can tell if they lived in back to back housing by looking at a large scale map – the 25 inch to a mile, like the one shown above is best. Using census records and, later, precise addresses on other documents, you may be able to work out the exact location on a map. Back to backs are identfiable by the line across the middle of what would otherwise appear to be one house. Each unit between the various lines was a separate dwelling. So you can see on the above map that almost every house in this part of Birmingham was a back to back. You can also see that some of the properties fronted on to the streets. These, being healthier and less malodorous, had correspondingly higher rents. However, far more of the properties were built in the courtyards: Birmingham had 20,000 of them.

The Public Health Act of 1875 allowed, but did not compel, municipal corporations to ban construction of new back to backs. By this time back to backs made up 45 per cent of Birmingham’s total housing stock, housing 170,000 people. Building new properties to replace them would have been a huge undertaking. It was not until 1909 that Birmingham actually prohibited the building of new back to backs. As new housing estates were built, the old housing was gradually demolished. The area around Inge Street and Hurst Street was designated for redevelopment in 1930, and gradually the courts were pulled down. However, Court 15 remained, and was inhabited right up until 1967. By the 1980s this little group of houses at the corner of Hurst Street and Inge Street was recognised as an important part of the social history of Birmingham – and indeed the country – and in 1988 the court was listed as a Grade II building.

It was not just the back-to-back formation and the cramped, unhealthy courtyard arrangements that made this type of housing problematic. It was also the number-of-family-members to number-of-rooms ratio; and this combined with the tendency for householders to take in lodgers, who often shared rooms or even beds with family members. Court 15 regularly housed as many as 60 people at one time. On top of this, there was the fact that the buildings themselves were quickly and cheaply built. There were no nationwide building regulations in 1831, and even when they did come into force in the final quarter of the nineteenth century, they did not apply retrospectively.

In fact back to backs are nothing unusual to me. My home town of Leeds still has about 19,000 such properties – about one third of the original number; and they are very popular with people looking for starter homes or on a lower income and preferring their own ‘house with a front door’ rather than a flat. I have been in many. The difference is that these 19,000 remaining back to backs are the better quality specimens. Some of them have small gardens, some have cellars and attics, and all are of sound construction. I wanted to understand the problems of the presumably 38,000 that were demolished. It was for this reason that I wanted to visit the National Trust Back to Backs ‘museum’ at Court 15.

Visitors to the site must pre-book on a guided tour. You can find out more and book tickets on the National Trust/ Birmingham Back to Backs website. The tours last about 90 minutes and you have to be able to climb (lots of!) very steep, cramped stairs with sharp bends and narrow, pointy treads. For people with limited mobility there is an alternative ground floor tour which lasts around 60 minutes and takes in the ground floors of each property.

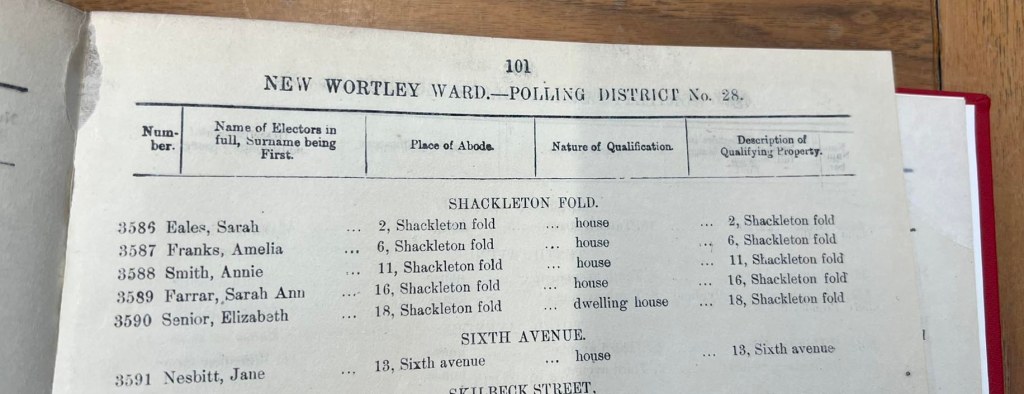

My tour did not disappoint – and in fact lasted two full hours. Our guide had grown up in similar housing a few streets away in the 1940s and 1950s and had actually known one of the residents of Court 15. He was generous in answering questions about life in the courts and even had a photograph of his family with a huge damp patch on the wall behind. There was nothing ‘nostalgic’ about the presentation: these were terrible places, life was hard and the streets were dangerous. We learned about sleeping with a pole to crush the bugs, we saw the most awful damp attic and the cellar where sometimes children slept, and we learned about actual families who lived in these houses and the lodgers who sometimes shared their beds. It was exactly what I needed to know to help with my Shackleton’s Fold One Place Study as well as my nineteenth century ancestry in Leeds and – just a short distance from Court 15 – in 1850s Aston.

You can take as many photos as you want while walking around the court and houses; and I did. However, this is a National Trust property, and it wouldn’t be right for me to include any of them here other than these two views that you can see from the street. So instead, I recommend that you visit! If you have ancestry in Birmingham or Aston, or anywhere else where back to back housing was considered ‘the solution’ to the rapidly increasing populations of the nineteenth century, I’m sure you would learn something from a visit to the Birmingham Back to Backs.

Additional Source:

National Trust publication: Back to Backs Birmingham, 2004 available at the NT Birmingham Back to Backs reception.