Last week’s post was about different levels of ‘taking control’ when searching on Ancestry, and this week we’ll try the same thing on Find My Past.

As with Ancestry, we’ll look at searches in the following order:

- A general search from an ancestor’s profile page

- A general search from the top menu bar

- Narrower searches, focusing on a particular category of record

- Focusing right down on one particular record set.

Again, the point is that by increasingly taking control of what your search focuses on, you’re improving the level of your own research.

As with Ancestry, you can follow a lot of what’s written here by working through it on Find My Past even if you’re not a subscriber. Obviously, you won’t be able to see the actual records.

And finally – if you already know all about general searches and homing in on categories, skip to point 4. There might be something new for you there. 🙂

*****

In Find My Past, then:

1. A general search from an ancestor’s profile page

Simply click ‘Search’ from an ancestor’s profile. I’m sticking with my GG grandfather, John Groves, born 1847 in Kinver, Staffordshire, and moving to Leeds, where he died in 1894. This search returns 6,449 records for my perusal, but there is also a reminder of how many hints I have for this person. Unlike Ancestry, this search filters only by name and dates, not by place, and only two on the first page of these 6,449 records are correct (although half of the hints are correct).

2. A general search from the top menu bar

From the top menu bar, click on Search, then Search All Records. An ‘All Categories’ search form opens:

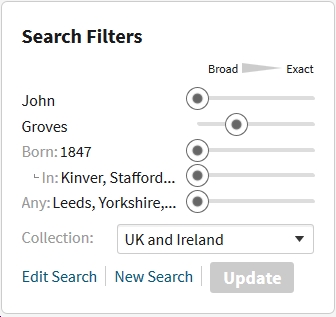

Here, you can input name, years of birth and death, and also a year for any specific event (which might be a marriage, a census year, etc). For each year, you can instruct the search engine to search for that year exactly, or to search plus or minus 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 or 40 years. Unlike Ancestry, FindMyPast will stick within those parameters chosen by you. However, Ancestry allows us to add more events with dates, and a place for each one. Here on FindMyPast, we’re allowed only one place name at a time. Since my GG grandfather John lived in different parts of the country, what I have to do is search in stages. My first search, for Kinver, returns only one record, and it’s not my John. Changing the place name to Aston, where I know he also spent some time, returns 61 records, of which the first is correct. Finally, changing the place to Leeds provides 128 results. Four of the top five are correct.

The main difference here between Find My Past and Ancestry is that FMP does require a more targeted approach from the outset, focusing first on place A and years x-y, then on place B and years y-z, and so on. Even so, my general searches returned a lot of records.

3. A narrower search, focusing on a particular category of record

Let’s now move to searching by category. We can start with that first general search from the profile page, but this time when we get to the results page (the one with 6,449 records) we can refine the search using the categories at the left of the screen and by adding in the location. Remember that in FindMyPast we need to keep changing the location if our ancestor moved around the country, and do a new search.

There are three things to notice:

First, you’ll probably find that far fewer records are returned.

Second, just as we can instruct the search engine to focus on a very narrow or a very wide span of years, we can also broaden the area of search, up to 100 miles from the named location. Although this doesn’t really help me with John, who migrated from one part of the country to another, it’s useful if, for example, you suspect your ancestor lived their whole life in Norfolk, but kept moving around for work.

Third, looking at the menu of categories to the left of screen, we can see how many records have been found within each category; and if we click on any one of those categories we can refine further, seeing exactly how many records there are in each sub-category. So, for example, for John Groves, dates as above, and a location of up to 50 miles around Kinver, I’m offered 483 results, 4 of which are in the military category, and I can see just by looking at the categories on the left of the screen that these are all Regimental & Service Records. This really helps us to home in on records that interest us.

As with Ancestry, we can also perform the same search by category from the top menu bar. Click on Search and then choose your category. Again as with Ancestry, the next screen will vary depending on the selected category. For example, the Census, Land & Surveys category has an option to include another household member in your search, and the Travel & Migration category includes departure and destination countries/ports. There’s also a dedicated category for the 1939 Register. I’m going to search for John in the Birth, Marriage & Death category, using name, birth and death years, and the exact location Leeds. There are 10 results: 1 death, 1 burial and 8 marriages. The death and burial are correct. Bearing in mind I hadn’t input any year for a marriage, I’m offered 8 likely dates between 1866 and 1893. One of them is correct: 1874. However, even though I performed my search in Births, Marriages & Deaths, I can switch to any of the other categories at any time, and I can see at a glance the numbers of records in each of those categories by looking at the list to the left of screen.

4. Focusing right down on one particular record set.

This targeting on Find My Past is very sophisticated, enabling a far more precise search than on Ancestry. Because of this, I rarely need to home in on a specific record set (the equivalent of the Card Catalogue facility on Ancestry), but if you want to, you can do this. Start with a search from the top menu bar. You can do this in All Categories or in any of the individual ones, but for this exercise you’ll get more results if you stick with All Categories. Towards the bottom of the page you’ll see there’s a box for inputting a specific record set. You can type in the exact record set name if you know it, or just a keyword. (Apologies for the image quality – I had to photograph the screen to avoid losing the pop-up record set suggestions when I clicked for a screen grab.)

Start to type in the name of your town, city or county of interest, and see what record sets there are. You can do this even if you’re not a subscriber, so it’s useful if you’re deciding which subscription service to choose. Of course, you can only view the actual records if you’re a subscriber.

*****

So, I hope there has been at least something new for you as we’ve looked at targeting our searches over the past two weeks. And having explored special record sets on Ancestry’s Card Catalogue and on Find My Past, I hope you’ve found something interesting to help you progress your research.

Go to the top menu bar on the screen, click on Search, and select Search All Records from the drop-down menu. Sticking with John Groves, but this time typing in his name, birth year, birth place and place of residence, instead of allowing the search engine to copy over the info from his profile page, this time I’m offered a whopping 352,536 records from ‘All Collections’, or 127,706 if I amend the collections to ‘UK and Ireland’.

Go to the top menu bar on the screen, click on Search, and select Search All Records from the drop-down menu. Sticking with John Groves, but this time typing in his name, birth year, birth place and place of residence, instead of allowing the search engine to copy over the info from his profile page, this time I’m offered a whopping 352,536 records from ‘All Collections’, or 127,706 if I amend the collections to ‘UK and Ireland’. So, you’ve clicked on Card Catalogue, and you have this screen (above) in front of you. As you see, you can still use filters (down the left) to help you home in on the record sets most likely to be of use to you. And if you know the full name of the record set you want, simply type that into the ‘Title’ box. You can then search just that record set.

So, you’ve clicked on Card Catalogue, and you have this screen (above) in front of you. As you see, you can still use filters (down the left) to help you home in on the record sets most likely to be of use to you. And if you know the full name of the record set you want, simply type that into the ‘Title’ box. You can then search just that record set.